The story up to now

Children play on the roof of Amritsar, the Wellington house that was a career-long project of Sir Ian Athfield (1940– 2015), an outstanding figure in New Zealand architecture.

Photograph courtesy Athfield Architects.

Architecture in New Zealand is an island narrative of exploration, arrival and ongoing adaptation, writes Bill McKay.

Our archipelago has been discovered by a succession of voyagers and explorers over the centuries but was one of the last significant land masses to be peopled. Around 800 years ago, in the last thrust of human expansion throughout the Pacific Ocean, expert navigators sailing sophisticated doubled-hulled vessels landed in the southern reach of Polynesia (‘many islands’) and adapted their way of life to a colder, more temperate land.

These people, Māori, built quite different structures from those in the Pacific. Low-roofed, single-roomed dwellings (whare) woven from plants were dug partially into the ground to insulate them from strong winds and cold. However, one feature that remained common throughout the Pacific was the marae ātea, a large, open space of communal, cultural and spiritual importance around which dwellings were clustered.

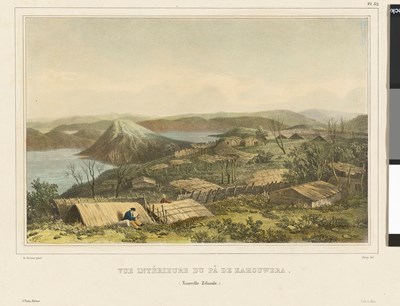

As the Māori population increased and society became more tribalised, strategic hillsides were secured during periods of warfare by large-scale earthworks and palisades known as pā.

The history of New Zealand architecture is not just one of arrival and the adaptation and evolution of building forms but also of transforming the landscape to meet the needs of people.

Throughout Oceania there is a strong relationship between the technologies required to construct ocean-going craft and those used to create buildings. What were once seen as simple dug-out canoes and grass shacks are now recognised as skilfully built structures that responded to local climatic and material conditions and that evolved in response to changing circumstances. The large double-hulled vessels became single-hulled canoes (waka), manned by paddlers and suited to coastal and riverine conditions. And the early whare, thanks to abundant timber and excellent woodworking skills, developed into larger structures bene ting from a rich carving tradition that culminated in elaborate elevated storage houses known as pātaka.

Orou under sail, Mailu, PNG, 1932. Photo: H. Bernatzik. Courtesy of the Photoinstitut Bonartes, Austria.

Orou under sail, Mailu, PNG, 1932. Photo: H. Bernatzik. Courtesy of the Photoinstitut Bonartes, Austria.

European explorers such as Abel Tasman (in 1642) and James Cook (in 1769) touched the shores of New Zealand in search of Terra Australis, the fabled Great Southern Land, but turned away, disappointed. Not until whalers, sealers and ax traders established more permanent contact did lawlessness and dubious land sales prompt Britain’s acquisition of New Zealand. The treaty signed by the British Government and Māori tribes was the signal for a rush of settlement after 1840 and a radical transformation of the landscape. Forests were felled, roads were made and new agricultural techniques introduced that rapidly affected native habitats, ora, fauna and, not least, Māori culture.

The New Zealand colonial project did not so much involve the adaptation of European architectural forms to New Zealand conditions as the transformation of the landscape to suit imported forms. In Auckland, then the country’s capital, the first government residence and Parliament were prefabricated kitsets. Most early dwellings were simple cottages, stripped of decoration and with rooms gradually added as means allowed. These early houses were nearly all constructed of wooden framing and cladding as a result of the extensive milling of timber to clear farmland, although in the south of the South Island, in particular, use was made of cob and other earth construction techniques.

Corrugated iron – actually steel, but known colloquially as tin – was used abundantly for roofing and even walls as it could be efficiently stacked and shipped to New Zealand from the factories of Britain. This was the same Industrial Revolution Britain from which mostly urban working and middle-class colonists were fleeing; for them, land in New Zealand was the answer to their aspirations for an agrarian lifestyle and improvement in social class.

Corrugated iron remains an iconic material in New Zealand, and the first choice for roofing domestic houses and constructing farm buildings. Although today brick is produced in reasonable quantities from the country’s abundant clay, it performs poorly in the land’s equally abundant earthquakes, and is generally used only as a cladding over more resilient timber framing. New immigrants to New Zealand are still surprised to see sprawling suburbs of typical timber and tin houses that seem not that much more technologically advanced than the dwellings of a century and a half ago.

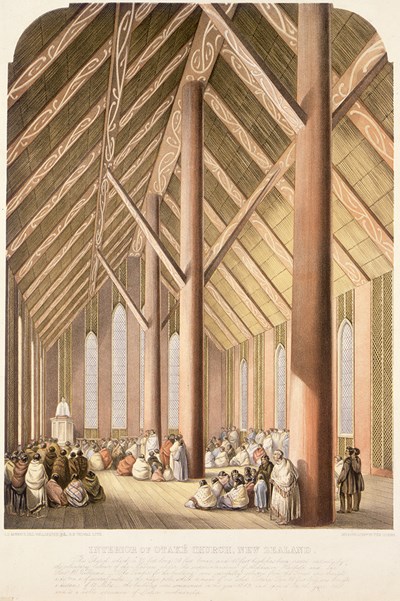

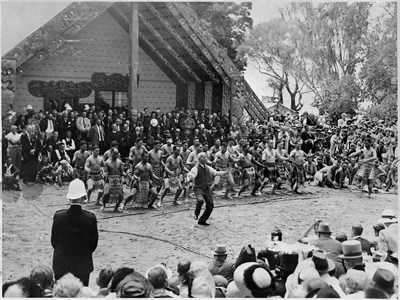

Conflict between Māori and the rapidly growing population of British settlers saw warfare from the 1840s until the 1860s. One striking building type arose from this conflict: the meeting house. Known in Māori as the whare nui (large house) or whare whakairo (carved house), the meeting house adapted European materials and techniques to compete with churches in scale, and provide a place for Māori to come together and discuss issues. The meeting houses became highly carved and decorated and supplanted pātaka and war canoes (waka taua) to become the centres of society and repositories of identity in a time of cultural erosion. Today, meeting houses – with their large forecourt open areas and ancillary buildings, known as marae – are perhaps the most significant architectural forms characterising New Zealand and Māori architecture and culture.

The late nineteenth century saw the creation of suburbs and the evolution of the cottage into the larger but still free-standing, single-storeyed and timber-constructed villa.

In the early twentieth century the bungalow arrived from the West Coast of the United States. The verandah had been a feature of early New Zealand houses and other buildings – it was also common in other lands colonised during the nineteenth century – and remains another iconic trope of the country’s architecture.

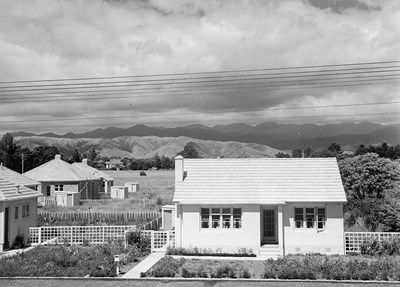

In the 1930s and ’40s New Zealand’s suburbs were expanded through mass social housing, namely the state house, which was derived from Britain’s Garden City Cottage movement. But this was the last time New Zealand looked to its ‘mother country’ for architectural inspiration. New Zealand was occupied during the Second World War, not by enemy forces but by American troops en route to the Pacific theatre. Before the war, New Zealanders referred to Britain as ‘home’; after the war, the country looked to the United States. The suburban house in the late 1950s and ’60s swiftly acquired the elements of the Californian Ranch-style house. With its open plan and free ow between the interior and the great outdoors – the perennial national preoccupation – this housing type remains popular today.

State house, Levin. Photo: John Pascoe. Ref: 1/4-001183- F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

One other icon of New Zealand architecture deserves mention: the bach, a small, shack-like holiday home near a beach or lake that many New Zealanders visited in summer. Some of the most interesting con- temporary house designs toy with, react against, or invoke the spirit of our various types: vernacular farm buildings, villa, bungalow, state house and bach.

The house has always been and remains a central concern of New Zealand architecture. It is central to the practice of most architects, surprising as that is to those in countries that look to other building types to satisfy architectural ambitions and express identity. In its first one-hundred-and-fifty years, New Zealand’s government, institutional and commercial buildings were largely similar to those in many other countries during the same period.

This isn’t unusual as New Zealand was one of the last transplants of the British Empire, and was expected to develop as a branch of imperial growth. Many of the country’s nineteenth and twentieth century buildings were constructed of brick and stone, but in scale they are small and in style they reflect the same concerns of Victorian Britain and its Battle of the Styles, although with marginally more Gothic Revival than Classical, especially in church architecture.

Schools, however, were more innovative in form, especially during the twentieth century, when a wave of progressive educational ideas also found architectural expression. Classrooms became large and sun-filled places that spilled onto verandahed spaces.

The destruction of the city of Napier in 1931 had a happy side-effect when the city was rapidly rebuilt in the Art Deco style, becoming for a brief period ‘the most modern city on the globe.

The first tentative arrival of Modernism between the wars coincided with a period of progressive thinking, an egalitarian social climate and a burst of industrialisation. Some new architectural ideas were expressed in factories and commercial buildings, albeit to a limited extent due to the effects of the Great Depression and the generally conservative taste of most of the population.

Modernism took off during the post-war economic boom. In the 1950s and ’60s there was a proliferation of new government, institutional and commercial buildings built in the concrete and glass International style. Brutalism was particularly important in New Zealand, and often featured concrete and blockwork that imitated timber post and beam construction.

At a time when New Zealand was self-consciously searching for a national identity it’s not surprising that Modernism, especially in domestic architecture, took on a regional accent. Architects argued that building form should acknowledge local climate, materials and the influence of vernacular structures such as the farm woolshed and the Māori meeting house. In contrast to this brief era of Regional Modernism, the late 1960s and ’70s saw a more relaxed aesthetic and a humanistic focus, a development that could be traced to international sources but also resonated with egalitarian inclinations, do-it-yourself attitudes and a vernacular revival.

The architectural achievements in these years were significant, even if they were mainly confined to the domestic realm, and did not greatly affect what had become a stifling atmosphere of dull commercial and institutional Modernism.

Post-Modernism landed in New Zealand at a time of radical economic and political change. Consequently, it was controversial.

Post-Modern architecture was regarded by some as laissez-faire looseness lacking a moral compass, and by others as an expression of freedom from the strictures of Modernism or the introverted preoccupation of generations with national identity. Recent decades have seen a welcome shift away from the house as an architectural focus and an improvement in commercial and institutional buildings.

Oddly enough, in a nation that has always been one of the least religious in the world, it is in New Zealand’s churches that one can see not just a clear rejection of the concerns of each period in our country’s history but also significant architectural achievement. Missionaries came to New Zealand at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Some of the earliest churches erected by Anglican and Catholic missionaries from the 1820s were built by Māori for Māori congregations using ax and raupō (bulrush) while incorporating imported elements such as lancet windows. These structures were early examples of a genuinely cross-cultural architecture that became even more significant in a group of large churches including Rangiatea (1851) at Ōtaki.

Early wooden churches were envisaged as temporary until those of ‘permanent materials’ (brick and stone) could be built, but a lack of good-quality stone and masonry skills, and the land’s tendency to quake meant that it was only large urban churches that were substantial. New Zealand’s settlement in the nineteenth century paralleled the period of the new and radical Gothic Revival, and spare, timber versions of this style of church, featuring a beautiful exposed structure crafted from native timbers, are widespread and constitute, as prominent historian Michael King put it, “our one memorable contribution to world architecture”.

Later-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century churches reflect the international Battle of the Styles with a series of Classical Revival Catholic basilicas, in particular, being a high point. But, again, it is the response of Māori to the pressures of European settlement that result in distinctively New Zealand adaptations of European forms to be at the service of Māori needs. This is seen over the course of several decades, from the Catholic churches of the Mill Hill missionaries (1890s), the churches and the revival of meeting house construction by Āpirana Ngata in the 1930s, and the churches and marae constructed by the Rātana movement in the 1930s–1950s.

The full-scale arrival of Modernism in the post-war period, combined with a spate of church construction in expanding cities, the liturgical reforms of Vatican 2 and a continuing concern with the expression of national identity, that led to a large number of remarkable churches that are distinctively of this country and no other. Examples are Richard Toy’s All Saints, Auckland (1958), and John Scott’s Futuna Chapel, Wellington (1961).

The twentieth-century revivals of Māori traditions and crafts have signified and contributed to the development of a bicultural society, and this development is now frequently reflected in architecture. There is a related openness to the architecture of other cultures, especially those of the Polynesian diaspora – the people of Tonga, Samoa and other Pacific islands – that make Auckland the largest Polynesian city in the world.

Today, immigration to New Zealand continues as it has always done and a new wave of immigrants from Asia will add significantly to the spectrum of the currently European, Māori, Polynesian, Indian and Chinese population. Given that New Zealand architecture consists of imported ideas and models that crash into or alight on our islands, that are imposed on or adapted to local conditions, it is only a matter of time until this new wave of immigrants contributes to a new architecture.

Architecture in New Zealand has never been primarily about form or function, landscape, materials, tectonics or climate: it is a cross-cultural conversation that has been at the heart of our best architecture since different peoples started meeting each other here.

As a young nation, New Zealand knows its past more immediately, intimately and obsessively than many, but, like any adolescent nation, is also very self-conscious of its present and its place in the world. The settlement and growth of New Zealand continues and as the increasing diversity of population connects our islands to more and more shores, these islands, in an era of contracting physical distances and new digital, virtual and multicultural dimensions, are looking to new and multiplying futures.

—

Bill McKay is a senior lecturer in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of Auckland and the author of several books about New Zealand architecture. This article first appeared in Koha − an offering of New Zealand Architecture and Design. A pdf of the publication can be downloaded here.