Gold Medal interview: Stuart Gardyne

From Wilton to the Wharewaka – and much more besides. Stuart Gardyne, the 2015 NZIA Gold Medallist, discusses what drew him to architecture and his approach to practice in this conversation with John Walsh.

John Walsh: To start at the beginning, Stuart – you were born and raised in Wellington.

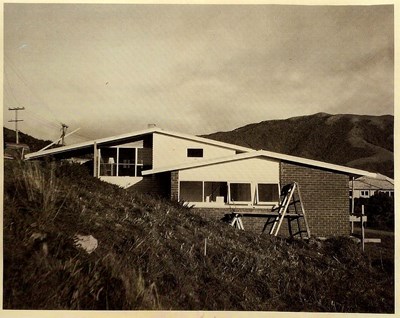

Stuart Gardyne: Yes, I lived for all my childhood in Wilton, a western suburb close to Wadestown and Northland. Wilton was a 1950s suburb with an interesting mix of architecturally designed houses and State houses and subdivisions occurring around us. You could roam on the weekends and get your feet muddy where the Euclid earthmovers had been busy during the week. I grew up in a house designed by Maurice Patience, a well-known Wellington architect.

Down the driveway a couple of houses away was a house designed by Alan Wild which Jane Aymer Aimer and her family lived in – Jane of course is an architect in Auckland now. Probably the best house in the neighbourhood was the one directly beside us, which was designed by Bill Toomath. We had interesting neighbours. The One family who lived in the Toomath house introduced me to contemporary New Zealand art – they had paintings by McCahon, Woollaston and Illingworth on the walls.

What did your parents do?

My father was an accountant. He grew up on a sheep farm in Southland, in a big Presbyterian family with lots of brothers. All of his siblings went on to be farmers but my father got poliosteomyelitis when he was five, so farming would have been physically difficult for him. My mother was a physiotherapist and she practiced as a physio during most of my childhood.

Where did you go to school?

In primary school I started out at Wilton School and then went to Wellesley College in Day’s Bay. I had very good teachers there, and Wellesley taught me a lot, including how to do maths, which, as it turns out, is pretty important if you want to be an architect.

What about art or design? Did they interest you when you were young?

There was a bit of art at primary school, but I became more interested in art at secondary school when we studied the Bauhaus. I remember, though, when I was still at primary school, going to the Wadestown library on Saturday mornings and being drawn to magazines with floor plans and photographs of houses. I enjoyed working out on the plan where the photos were taken.

I think just living in an architecturally designed house, and in a neighbourhood with architecturally designed houses, was some sort of influence.

You went to Wellington College. Did you enjoy your time there?

Wellington College was a traditional boys’ school. You wore a cap, I was going to say you wore a tie, but that may have been only when you got to Seventh Form. This was the early ’70s, and there’d be hair checks at school. You’d tuck your hair behind your ears and pretend it was short. But generally it was a good school. Of course school is so much about your friends – the people you spend your time with, and the experiences you have with them.

You and Janey have been together a long time. When did you meet your wife, Janey?

We met when I was 16, at the Christian Youth Movement, CYM it was called, at Wadestown Presbyterian Church. It was really a social club. On Sunday evenings we’d go there with lots of friends, and we’d go on camps and all that sort of stuff. Christianity isn’t something that has continued in my life but I think values of community have. I believe in social equality – it’s very important that we get on with each other and help each other. What we contribute to our community is what makes our lives valuable and rewarding.

Architecture, to me, is very much about providing desirable places for people to live, and which support people to lead the lives they choose to lead. Whether my beliefs come from my Christian upbringing, I’m not sure, but certainly my beliefs about equality are very liberal.

At high school did you consider architecture as a career?

I started secondary school knowing I wanted to be an architect. I found it extremely unusual when one of my colleagues at the School of Architecture finished his degree and immediately went and got a job as a stockbroker. I just didn’t understand how you could have gone through so much of your life only to discover this isn’t actually what you wanted to be. Now I realise that most people have some uncertainty about what they want to be and many change careers. Janey started in aid and development and then became a landscape designer.

What was the process of getting into Architecture School when you enrolled at Victoria University?

You did what was called Architecture Intermediate which was maths, physics, human geography, cartography, psychology – those sorts of subjects. I took two years to get in, but even when I wasn’t accepted the first time I didn’t have any doubt that architecture was what I was going to do.

It used to be said that the Victoria University School focused on the construction side of architecture and that the University of Auckland School was stronger on design.

That was the perception, and perhaps it has persisted, but in terms of design credentials the Wellington School was right up there. Some very good lecturers taught some very good students at the Wellington School. I suppose in the late ’70s, when I started at the School, it was a little more holistic, you might say, in the way it approached architecture. This was due in large part to teachers like John Daish, John Gray, David Kernohan and Duncan Joiner.

What books do you remember from those days?

One text I still refer to is Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language. Some people think the book is about the ‘touchy feely’ side of architecture but to me it epitomises the holistic approach to architecture. It’s about the ways that individuals and communities might live, and the ways in which cities are formed from a macro to a micro scale. Another book from that time which was very influential was Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

You went to the VUW School at the time Ian Athfield and Roger Walker were causing a stir in Wellington.

Their work didn’t really impinge on the School, although it had already had a massive influence in Wellington. Wilton was studded with Roger Walker houses, and there were houses by Ath all over the rest of the city. Practices like Craig Craig Moller were active, and you could find houses by the mid-century Wellington masters – Bill Toomath, Derek Wilson, Jim Baird and Bill Alington – all around the western suburbs where we lived.

There wasn’t much practitioner influence on the School?

Not really. I distinctly remember John Scott coming to the School once. He had a commission to do a house on Seatoun Heights and as students we were given the site to do a design for as well. I have no recollection of my solution, but I certainly remember meeting John Scott. The thing that interested me most about him coming down to look at the site was that he camped there. He would pitch a tent on the piece of land where he was going to design the house.

What were your choices when you left Architecture School?

I just assumed I would work in Wellington. Architecture in the city then was quite vibrant and there was a lot happening. I applied to Structon Group, Athfield Architects and Craig, Craig, Moller for work, and accepted a job at Structon Group.

Why that practice?

It was a large firm, and it was mostly doing commercial work and that interested me. The projects I worked on during the ’80s at Structon Group were pretty much exclusively commercial – new buildings as well as office fit-outs. Structon Group has an extraordinary history as a training ground for architects. In my own practice at least half a dozen of us worked there. I’ve been with some of these people for all of my career. Arniey Makin and Craig Thomson, for example, who are technicians in our practice, started at Structon Group at the same week as I did. It was a really good place to learn about putting buildings together with some really talented people.

I never had a desire to go overseas and work. I got wrapped up in life here, and I wasn’t a moth drawn to the flame of any particular architect overseas.

Halfway through Architecture School I took a year off and went travelling with Janey but I didn’t feel the need to move offshore. Perhaps I didn’t have the confidence, either, to do that. And, then, Janey also had work here.

Structon Group in the early ’80s – was the firm having a post-modern moment, like many New Zealand practices at the time?

In the late ’50s and ’60s Structon Group designed some beautiful buildings in a modernist, mannerist sort of way. It wasn’t a dry modernism, but very unusual – Structon did the Manchester Unity Building on Lambton Quay, with its coffin-shaped windows, and the celebrated Racing Conference Building. One of my first jobs at Structon was to put a canopy around a building on Featherston Street – I think it was the Royal Insurance Building. The building came down to the street in a glass façade except at the entrance where there was a canopy which had the gull wing shape of the Chevy owned by Ron Muston, one of the firm’s directors. My task was to extend the canopy around the entire building – you didn’t want to pull that gull wing off and replace it.

But certainly the early ’80s were post-modernist years. In the late ’80s de-constructivism was rearing its head. I guess we went from Charles Jencks to Mark Wigley. It was very much a period of trying to understand what architecture was about. The post-modern period made architects look back at pre-modern architecture, and hopefully see that architecture is a continuum. I distinctly remember being a fan of Edwin Lutyens who was practising in the early twentieth century. My research report in my last year at the School of Architecture was about Wellington architecture in the inter-war years, which was a transitional period when there was massive change from the Gothic and the Classical to modernism, via stripped classicism, neo-Georgian and art deco. There was an enormous amount of change in those two inter-war decades. Before the First World War there was nothing modern of any consequence, and after the Second World War there was nothing traditional of any consequence. It’s hard to imagine a period in architecture where there was such a massive change in such a short time.

In the early part of my career the New Zealand architect I admired most was William Gummer, who was responsible for the Carillon, the National Museum, Wellington Public Library, which is now the City Gallery, and buildings in Auckland such as the Railway Station and the Dilworth Building. The Gummer building I probably most admire is the original State Insurance Building in Wellington, and then the one beside it, the second State Insurance Building which is still standing with the Athfield addition on top. Those were extraordinarily accomplished buildings. Gummer’s skill as an architect is probably under-recognised. He was an absolute master in terms of the way he put space together.

One of the most rewarding projects of my career has been the work on the City Gallery which was essentially re-purposing the old Public Library. I think the reason it works so well as an art gallery is because Gummer’s rooms were such beautiful spaces. The proportions are just extraordinary. The work on City Gallery has had a very strong influence on my career.

You’ve discussed your liking for the modernist architecture of the inter-war years. Modernism of course was more than a style – it had a social dimension as well. Its association with a more egalitarian politics presumably resonated with you.

I mentioned how Wilton was a mix of state houses, builders’ houses and architecturally designed houses and it’s interesting to look back and try to understand who lived in those different houses. We were all the same kids at the school but our parents were different in terms of what they did and, of course, the houses that architects were designing were houses for the professional sort of family. Ironically, given their social agenda, the state houses were in many respects old-fashioned houses. They had a very traditional English feel about them. They didn’t feel modern, while of course the whole state housing programme was very much about the brave new world.

The mid-century modern houses in other parts of the world – houses like the one in Sydney that Harry Seidler designed for his mother [Rose Seidler house] and many of the Case Study houses in California – were very much homes for the affluent. The houses architects were designing in Wellington were very different. They were modest little houses for professional people with a bit of extra money and aesthetic ambition.

Materials were hard to come by, and the houses were small. I quite like the modesty of those little houses in Karori and Ngaio. There’s something far more captivating about achieving something with a paucity of means.

How long were you with Structon Group?

About ten years. I was a director for five of those years – I became a director at a relatively young age, and it was fascinating. You don’t get taught how to run a business when you study architecture and it’s not something I necessarily enjoy or feel drawn to, but you have to do it. I was given a lot of design freedom at Structon and I’m extremely grateful for that.

What are the projects you worked on at Structon that remain important to you?

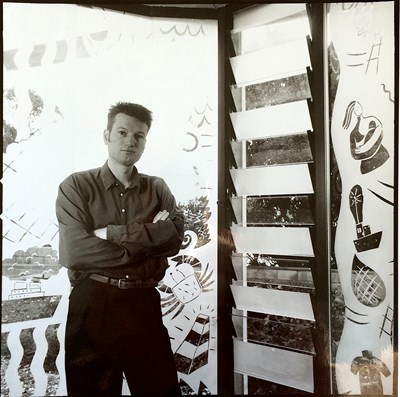

One in particular I remember was an office interior for the insurance company General Accident, in a building that Structon Group had designed twenty years earlier. That was the era when there were still companies that built for themselves rather than occupying a building built by a developer. I distinctly remember the General Accident job happening in the punk and new wave period. I commissioned Malcolm Benham, an artist who also ran a Courtenay Place café called Inck in the early ’80s. Malcolm invited me to an exhibition in his home by a contemporary of his. I think the paintings were for sale for about $100 each. The artist was Bill Hammond and I thought they were bloody awful.

Do you still think that?

I’m now a fan absolutely love some of Bill Hammond’s work, although some of his stuff from the early ’80s I still find macabre, but it usually takes time to appreciate the work of people who push the boundaries. That’s true, of course, in architecture. Anyway, I got Malcolm to do some designs which were sand-blasted into glass and used in the project. But what I remember most distinctly about that fit-out is that I was very conscious of the tyranny of the two horizontal planes. You’ve got a floor slab with a ceiling 2.7 metres above it, and from a spatial perspective this is quite constricting. In that interior I did whatever I could to change the perception of space.

I suppose I was in that stage of a career when you’re trying to be architecturally interesting and drawing on influences which might be more appropriate in other project types. At that time I was very much focused on how to deal with three-dimensional space – the issue of the pancake between two surfaces – and that has remained a concern throughout my career. For example, the Department of Health fit-out [Wellington, 1989] is very much about the three-dimensional interlinking of multiple levels.

This Department of Health project I did in the late ’80s in Wellington is also about linking spaces and changing separate spaces into a community. In both of those projects it was, I think, important for all individuals within an organisation to be able to have an understanding of the full extent of its business. A lot of our recent contemporary office buildings are designed around this sort of concept – the three-dimensional atrium space as the heart of an organisation. Conservation House, Spark Central in Willis Street and the Hutt City administration building are all examples of this.

The issues around how a building is used and inhabited seem to have been career-long concerns for you.

An architectural project is not just about the building. It’s about the occupation of the building. When I was in London in the early ’90s I visited the original Saatchi Gallery, which was in an old paint factory in St John’s Wood. It was a really nice gallery. The architect of the conversion was Max Gordon, who did a lot of work for people in the art world. He was clearly committed to a sort of minimalism – I think there was an article about him which was headed ‘No Trim’ – but what I found most interesting about him was his strong belief that his work wasn’t complete until people had occupied it.

At the School of Architecture I remember John Gray, one of our lecturers, would produce beautiful hand-drawn plans, and he’d always draw the furniture. I thought that was really interesting and I’ve tended to do that as well. People say that when Marshall Cook visits a house the first thing he does is find the most comfortable place to sit, and from there he contemplates the space around him. I’ve tended to do the same sort of thing. Finding somewhere where you can feel comfortable is very important.

A lot of the work I’ve done has been corporate interiors and offices. The focus of these interior projects is how people use the space. You’re not really changing the container. Maybe you’re trying to do stuff with the ceilings, create openings through from floor to floor, get some connectivity between different parts of the building. But typically you’re given a space, and you have to use it in a sensible, efficient way and make it a good place for people to work in.

The thing we’ve learned is that offices can change quickly – the organisation of the staff, the number of the staff, the size of the teams – and so you have to create something that can cope with change. Something which means you’re not spending money every five minutes to put up a new wall or move people from one part of the office to another.

That said, fit-outs and interiors can be a little frustrating. You can go back to a project after five or six years and find that somebody has decided, ‘We need to create a room here’, and you’re not sure why they thought that. It may just have been somebody made a fuss and said ‘I need an office’. But I don’t think we’ve gone back to many offices where people have changed things that much.

With a lot of corporate work what the office looks like and what objects are within it are not the important parts. What’s important is the organisation trying to express its character – it might want to try to be young, or funky, or corporate, or conservative. Currently we’re working in the same building for the Tertiary Education Commission and the Commerce Commission. The two interiors need to feel different because the people and the work they’re doing are different. But apart from a couple of aspects those organisations are not fundamentally different in terms of the way an office works. Ninety percent of offices could be almost identical. The differences lies in just a few things.

What made you leave Structon Group?

I didn’t think I was developing or moving forward, and then there were the flow-on effects of the 1987 share market crash, which really started to hurt the Wellington construction economy and jobs dried up. But probably the most significant reason was that I was asked to design the City Gallery. Paula Savage, the Gallery’s director, wanted me to be the architect. It was a Wellington City Council project and those jobs normally went to the City Council’s own architecture department. Paula Savage didn’t want the Council’s architects to do the design, but whoever was chosen would have to have a working relationship with them. When I was selected as architect to do the project, I had to take a leave of absence from Structon to work on the project.

There were a couple of very good architects in the City Council’s architecture department, on the technical side in particular. One of them was Graham Allardice. Graham could be a bit of a curmudgeon, but I found out later that the house I liked the most in Wilton when I was growing up was one which he’d designed for himself. The other thing I also found out was that he designed the bucket fountain in Cuba Mall.

Looking back, how do you evaluate the City Gallery project?

It was an extremely important job for me. Fundamentally, it involved the creation of a contemporary art gallery in a building designed to be a public library. I’ve always regretted that the money was never there to project the gallery into the wider urban realm. The relationship of the building to Civic Square is very mute and hasn’t really changed from when it was as a public library. But now – and this is the third time I will have worked on the Gallery – we’re looking to better signal that there is a contemporary art gallery here, not a public library. And that’s wrapped up in a much bigger project, which is trying to get Civic Square to work more successfully.

The City Gallery building is a relationship between old and new. It’s about making the old and the new speak equally; it’s not about trying to cover up the past or remove traces of history. Instead, we wanted to convey a sense that this is our place in time but there have been previous occupations of the site and there will be other occupations of the site in the future.

I’ve found this to be a fascinating way of understanding architecture. One of the most profound buildings I’ve ever visited – this was in the ’80s – was a building in Norway by Sverre Fehn. He did relatively few projects, but some of them are phenomenal. This building was the Hedmark Museum in the town of Hamar. I didn’t know the building existed and only found it because I was in Norway and in a guide book of European modern architecture there were perhaps two listings for Norwegian buildings. One of them – the Hedmark Museum – was nearby so I thought I’d better go and see it. It’s basically an old ruin which Fehn had re-purposed, and the way he had treated it was extraordinary. Visiting that building had a big influence on me in terms of my understanding of City Gallery as a design project.

City Gallery was your break-out project?

It was. I’m probably not that good about deciding what I want to do. I tend to go with the flow, sometimes making decisions not to do things but infrequently making decisions to do things.

At City Gallery something happened which led me in a direction which I had not expected to go, but the consequences have been extraordinarily significant to my career.

As I said, I needed to develop and having worked on the Gallery I didn’t want to return to Structon Group, so I set up my own practice immediately.

What sort of projects came to your new practice?

One of the first significant projects was a fit-out for the Film Commission in the old John Chambers building, the sort of Flat Iron Building where Jervois Quay and Cable Street split. It was a fascinating job – what do you do for a client which has such a specific focus, which is New Zealand film? How do you do something that evokes some sense of who we are as a people? In a way the job was a natural progression from City Gallery. It was very much about the question of how do you adapt a building, the issue Carlo Scarpa handled brilliantly at the Castelvecchio [Verona] and the Querini Stampalia [Venice].

I’m very much drawn to this sort of architecture. Our own house is an example. It’s a Victorian house next to a little ruin with a vine growing on it and an old shed which I don’t want to pull down because I like its rusty corrugated iron. I’ve realised that virtually everything that I do in architecture is contextual. It’s not just about the land, it’s also about the society, the culture of a place, and the time in which a building occurs. For example, Pataka, the museum in Porirua [1997-8], is very much about that city and the time – the late ’90s – when it was built. Darcy Nicholas, who was the director of Pataka, insisted it be called the Porirua Museum of Arts and Cultures. I thought it must be ‘Art and Culture’, but he would correct me and say, ‘No, cultures, plural. Porirua City is a city full of many different sorts of people’. There weren’t only Maori and Polynesian people. There’s a strong Scottish community, and a community from Austria – the builders who came out to do state houses in Titahi Bay. Darcy wanted a building for all of the people who live in Porirua.

I think architects can pull together aspects of society and culture in their work. At Futuna Chapel, John Scott brought together his Mãori and Scottish heritage and Catholicism, and created something which speaks of all of those but is none of them specifically, either. What we were trying to do at Pataka was find a New Zealand architecture which somehow spoke of contemporary New Zealand society and the influences which had led to that. It was also about trying to realise a building which the local workforce was capable of building in an economical way. The Labone cabin [1997], in a different way, also tries to bring together the vernacular and modernism. It’s about a very specific piece of landscape, on a hillside in the Wairarapa and the desire of the client for something which suggests a retreat and expresses a degree of nostalgia that engages with the land and which references design precedents in a considered manner.

The Wharewaka [2001-2011] on the Wellington waterfront would seem to be a something of a departure for you. How does it fit into your body of work?

It was a real privilege to design the Wharewaka. That was our first real opportunity to be involved with a project beyond the pakeha culture of New Zealand. I’ve always thought this is a unique place in the world because of our relationship with different cultures, and the tangata whenua in particular. That’s something which I’ve always felt extremely proud of – you know, just being a New Zealander, and the way we live and the way that I think we have tended to engage and treat each other as people. I’ve started to question that as I get older and am now a bit more cynical about the way New Zealand culture and society can be at times, but it’s a small country and it’s very easy to feel you understand it and know it.

Is the Wharewaka a Maori building?

I don’t think I can define whether something is Mãori or not. It’s a building owned by an iwi-based organisation with functional requirements and business objectives. The Wharewaka may have some Mãori characteristics and decoration, and also a lot of it expresses some fundamental ideas about what a building means in a Mãori context which might be different from how an Anglo-Saxon person might see a building. I was a bit surprised to find when [Irish architect] Niall McLachlan spoke about his acclaimed Bishop Edward King chapel in Oxford that he also has an understanding of the way that buildings in an Irish or a European context can be about the embodiment of the body, of the mind, of the soul. But in New Zealand, Western culture has largely become divorced from that way of seeing a building.

Your more recent work seems to be characterised by more abstract composition.

This is something that has crept into our work, and for this I can probably credit Michael Bennett who I work with. I first worked with Michael when we were at Structon Group and I think a lot of the good work that has come out of our office has been the result of our collaboration. The project where we really got into abstraction the most was the City Gallery extension [2006] – the rusty steel box out the back. It’s probably one of the few projects we’ve done where the tectonics, the way it’s put together, are not evident. There’s a skin that conceals a lot of the building’s construction.

The Wharewaka, which followed shortly after the City Gallery extension, is the complete inverse of that. The structure and the bones of the building are very evident, much as Mãori architecture is the embodiment or representation of the human body. At the Wharewaka the structure of the building is the skeleton and the skin of the building is the cloak that covers that body. The Wharewaka has a sort of abstraction in terms of the cloak, but it’s far less abstract and more figurative in terms of the way it’s put together as a piece of architecture. The Wharewaka’s triangular forms became more abstract as the project developed. Initially, the idea developed when we were working with Mike Barnes on the project ten years before it was completed. Mike introduced the idea of the cloak, and it resolved so many issues in terms of the building being a pavilion seen from above and from all the sides, whereas you normally see a Mãori whare from the front. You see just the front elevation. With the Wharewaka the sides, the back and the top are just as important. The idea of the abstracted triangles came from the idea of the patterning, and evolved into the very large elements which relate to the structure of the building. It became almost a supergraphic.

Do your ideas for a project come at the start or do they emerge over time?

At times Michael has been frustrated with me because I haven’t had some concept or idea at the early stage of a project. I think the more we work together the more we’ve come to appreciate that the way that a project becomes what it becomes is due to the design process. You don’t know what a project should be until you get into it and start to understand what the issues are. It’s very much about finding out what the project means and then, at some point, it becomes clear as to what the project needs to be. I don’t really like talking about a big idea because often there isn’t one. The Wharewaka might be one of the few projects where I can actually say there is a big idea – the cloak. But even then the ideas was just a vehicle. It was part of the process that allowed the project to move forward in a meaningful way. But at a higher level I believe the big idea is the same for all projects. That is about space and inhabitation.

I can see that your personal beliefs and social inclinations are immediately compatible with projects such as City Gallery, Pataka and the Wharewaka. But of course you have to work in a capitalist system for monied or corporate clients.

I don’t see that commercial clients are really any different from social clients or individuals. What a commercial developer is attempting to do is create an environment in which people can work. It’s not just about maximising return. It’s about creating something which meets a functional need, and doing that successfully so that people want to lease a building. It’s also about creating something that contributes positively to a street. The Telecom Spark building [2007] on Willis and Boulcott Streets is very much about that. That building works for Spark, but it works for the city as well.

Was that in the brief or did you put it into the brief?

It was in the brief from the developer, Ian Cassells. The building was named Willis Central, then Telecom Central and now Spark Central and the word ‘central’ is important – it’s about being in the heart of the city. Wellington is very much a walking city, and I think Ian believes its compact quality should be reinforced. I agree with him. Ian Cassells makes decisions for commercial reasons, but he also understands the city as a whole – as a place where people live, work and have a life.

You’re a Wellington enthusiast, aren’t you?

Wellington has some very interesting character. Take the northern end of Lambton Quay, for example, which is a beautifully scaled urban environment. There’s that wall of buildings, with Plischke and Firth’s Massey House next to Structon’s Manchester Unity, which is a lovely height, and over the road were the State Insurance buildings. Eight to ten stories in a commercial district can be a very good scale. The other day I was looking at some photos of very tall buildings in New York by Raymond Hood. The buildings are unbelievably lovely to look at – the colour of the stone, the way that the light falls on it, the relationship with the leafless trees. But as an urban environment, the footpath below these things is not necessarily a pleasant place to be. I’ve always loved Scandinavian cities, Copenhagen in particular, because of the scale of their cities and the extraordinarily careful and beautiful way that Scandinavians put their cities together.

In complex projects, what is the architect’s role?

Making things happen can be extremely hard. There’ll be conflicts and compromises, but often you get a better outcome because of the challenges you’ve faced and have had to resolve. You can’t necessarily anticipate the outcome at the beginning of the process.

I remember during the Wharewaka project sitting in our meeting room with a dozen people – clients, engineers, project managers – and as the discussions went on I realised I was the only person in the room who was thinking about the whole project.

Nobody else was trying to synthesise disparate objectives and pull them together. I guess I could ask why it was so late in my career that I realised people probably expect that the architect has to provide this role. I much prefer to sit and listen than to be out there espousing a position or trying to bring people along with me, but that day I realised my role was to pull everything together and synthesise it into a design solution. Nobody else can. From that time on I felt far more relaxed.

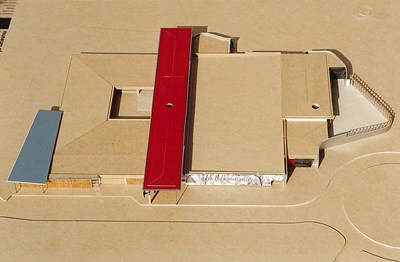

Civic and urban work morphs into the political realm, and that’s a challenge in itself. I think we, as architects, should be grateful that we’ve got people like Pip Cheshire and Patrick Clifford who have political skills – who are able to take architectural and urban design skills into that wider realm. For me, working in Christchurch for CERA (Christchurch Earthquake Recovery Authority) on the Convention Centre project has been fascinating. It has opened a window into a world which I didn’t really know existed, if that makes any sense. We’ve done a lot of work for central and local government but when you’re actually embedded in central government you get a completely different understanding of things, such as process, and how decisions are made.

Where are you at now, with your career and your architecture?

I haven’t really thought about it. Well, I have thought about it but I’m not necessarily sure that I can articulate it. Look at the snow on the hills over there – it’s absolutely lovely.

Is that your answer?

To a certain extent it might be. I mentioned that halfway through the School of Architecture I took a year off and went overseas. That was my first experience of big cities – I went to New York and Hong Kong, the most dramatic urban places in the world. So certainly in my twenties and thirties I was drawn to urbanism and architecture in the urban realm. Now, and it may be partly to do with my deafness, which is getting worse, and must also be to do with age, I find I prefer being away from cities. I like being out in the bush or at the coast. I’m increasingly drawn to the landscape more now. Even when I’m out in the country I don’t want to be inside, I want to be outside. As I’ve said, my father was from a farm. I always knew I was going to be an architect but I could also see myself as a farmer.

Of course, that’s only part of the story. The reality is I absolutely love buildings and two projects that are occupying my thinking more than anything at the moment are a cabin which Janey and I want to build out at the South Wairarapa coast, which is very wild, and a house for clients on Great Barrier Island. Great Barrier is a slightly magical place. I’m really proud of the design for the house there. I just feel that we have brought together lots of ideas into a place where you’d want to spend time on Great Barrier Island. It’s not a design or a plan or a house which would necessarily work in other parts of New Zealand, but I think it will work really well on Great Barrier – in that particular climate, for these particular clients and on that particular sandy piece of land close to the beach.

Finally, let’s talk about architecture as the art of the possible. For all the difficulties and obstacles, you have an opportunity to make things better.

I think it was Corb who said it’s better to have one beautiful thing than many ugly things, or words to that effect. While the work I do might seem to be more about creating space, I care a lot about what a building looks like – the composition and beauty of the materials and the way they’re put together. As a practice we don’t necessarily have the obsessive resolve or desire to craft our buildings. The selection of the ceramic tiles and where things are put are details – I care about these things, but for whatever reason I don’t have the resolve to pursue them in every project, or every part of every project. Just thinking about it makes me realise we probably need to get other people into the practice who have got that real desire to do those things. But if we did I’d probably be concerned that we’d get too obsessive, too tight, too controlled.

I recall going through City Gallery with Patrick Reynolds and saying I was disappointed about something, and Patrick said, ‘You don’t have to be staunch about everything’.

And it’s true, you don’t. The reality is that sometimes you can’t control things, and architecture is not actually about controlling things, although it is about order. You’ve got to get to the stage where you realise it’s all about creating a venue for living. That doesn’t negate the fact that a building should be beautiful. You can and should create great living environments – there’s no pleasure if they’re ugly. A building, whether it has rich spaces like those Eames created or more austere spaces like Arne Jacobsen designed, has to be enriching of the soul. You’re designing a building or a space for the people who are going to be in it, or occupy it. You’re not doing it for yourself.