Roger Walker

Gold Medal interview

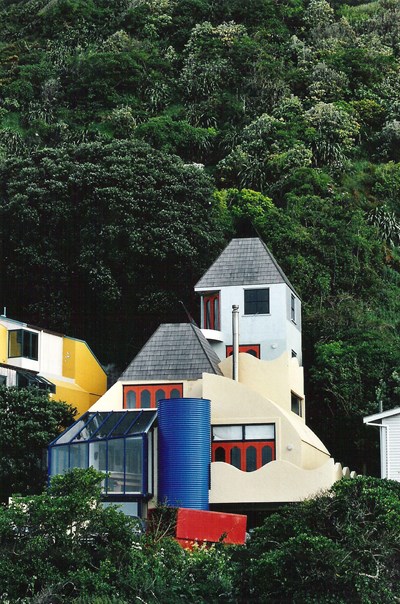

Sandcastle Motel, Peka Peka

Few figures in the history of New Zealand architecture are as synonymous with a place and time as is Roger Walker with Wellington in the 1960s and ‘70s. John Walsh sits down with the architect and goes back to the beginning.

John Walsh: Roger, shall we start at the beginning and stop at way stations along the journey?

Roger Walker: Pause for a cup of tea?

Or something... You’ve spoken, at various times and engagingly, about growing up in Hamilton, which you have memorably described as a superphosphate society built on a swamp. Your interests were drawing and making things, not rugby union.

I was a bit of a frail child.

Were you an only child?

No, I was the eldest of three.

What did your parents do?

My dad was a chemist and my mother was a doctor’s receptionist before she retired. In those days once women started having a family they stopped working, or left paid employment, I should say. I was born under a picture of the Queen. I had a very straight, semi-religious upbringing. It was a little stressful in that friends were not encouraged to come home, so even though I had some dodgy cousins I was forced to spend time with them because they were family.

I got on well with my brother and sister. My parents were strict but they were also loving. We had the quarter-acre section but, as you say, we didn’t kick a football around. We drove a go-cart around at high speed and churned up the lawn. My parents were enormously forgiving. My brother and I built a hut in the backyard which is semi-famous now. That was my first encounter with town planners.

This was the celebrated Fort Nyte.

Yes, I built it when I must have been going through a slight misogynistic period – there was a big sign, ‘Girls Keep Out’. The hut got higher and higher. It started off because a primary school was being built next door and there was a mountain of offcuts just over the fence. I asked if I could have some and the builder told me I could have the lot because it would save him having to pay to have them taken away.

Mum was quite accepting of this structure which grew organically in the veggie garden. It ended up being quite hostile in the sense it had a 44-gallon drum on the roof with a shanghai. Perhaps this was a way of attacking suburbia. Because it was the tallest building in the neighbourhood the planners visited one day. They said it was exceeding the height limits and blah-blah-blah. So I had an early encounter with bureaucracy.

Roger Walker (2016). Photo: Simon Wilson

Did you already think suburbia was boring?

Well, I had problems growing up in suburbia. I couldn’t understand why a pile of loose building materials and bricks would arrive on sites and then morph into identical houses.

This was the 1950s?

Yes, in the suburb of Fairfield. It was classic brick-and-tile suburbia. I had developed a bit of an antipathy to the conservative values that came out of that. I remember a guy wanting to do a pizza parlour at the end of our street and all the neighbours said, “Oh, no, we can’t have Italians in our street.” The most interesting building in the neighbourhood belonged to a company that repaired bulldozers.We used to get steel ball-bearings from there and crush the other kids who just had plastic marbles. One day of course that building disappeared. It had to go. It was an eyesore in a nice suburb, and was replaced by another clone of a house.

I really didn’t know anything about architecture at that time.When I was at high school I told the vocational guidance woman that what I’d really like to do is design cars. Part of the psychology of growing up in Hamilton was escaping – escaping the hum- drum and the stultifying physical environment.

My brother Gavin and I were into cycles. We would have an argument with mum and dad who would find us 20 miles out towards Morrinsville and say, “All is forgiven, come home, your tea’s getting cold. Then we got into go-carts and trolleys.”

Sorry, I distracted myself... The vocational guidance officer said, “You can’t design cars in New Zealand – there’s not an industry here. You’ll have to leave the country.” I said, “I don’t want to leave. It’s a beautiful country and I was born here.” She said, “Well, you can design buildings,” and I said, “Buildings? They just go up and come down again.” She said, “Trust me on this one, they are designed – by people called architects.” So I said, “Well, I’d better do that.”

What did you make of Hamilton Boys’ High? I presume it was a rather traditional state high school.

Looking back, I enjoyed school. The teachers were stimulating.We were quite mischievous. There was a nasty mathematics teacher and we picked up his Mini one day and did a Mr Bean – lifted it up and put it in a place where he couldn’t get it out, that sort of thing. I enjoyed the education and learned a lot.

I enjoyed English. I didn’t enjoy mathematics particularly but I liked science subjects. The school did teach us to question things and make up our own minds so it was very progressive in that way.

From school I went to Auckland University. I really blew the first year. It was a break-out year, if you like. I got into snooker and girls and drinking and lost my high school bursary. I think I passed English and that was about it. The next year I thought, “I’ve got to do this properly.”

Where were you living when you went up to the School?

In a religious hostel. Because of my Methodist upbringing my parents got me into Trinity College which was at the top of Grafton Road. There were people like David Lange there, training to be ministers. There was a sort of camaraderie and a bit more mischief, but it was also liberating to be in a big city where there were people of different ethnicities. I knuckled down in my second year. I thought I’d do geology because the lecturer was never going to say, “From your high-school notes you will have reached this point.” Psychology and geology were two subjects that you started from ground zero.

I was interested in how the earth was formed. How did mountains and rivers come about? What are the processes?

I finally managed to pass physics and so I got into the School of Architecture in Year 3. That was incredibly stimulating. Peter Middleton was there, and Vernon Brown – that was his last year before retiring. Imric Porsolt really embedded a sense of history and what was happening in Europe, and put New Zealand in context. He didn’t put New Zealand down but clearly established the pecking order of architectural history and that was very important to me.

One of the most important people at the school was Professor Toy. He could speak for three hours about the difference between an orange and an apple – about how the fruit was created, and the way it was subdivided, and way it hang.Toy was a fascinating poetic influence.

There were strange architects from Christchurch, Peter Beaven and Miles Warren, who used to come up and give impromptu talks to the students.That was incredibly stimulating. Vernon Brown was influential because he was so honest and brutal. The Professional Support Group I now belong to has a couple of academics, and one of them asked me, “What sort of things happened in your education in Auckland in the 1960s?” and I told them we had people like Vernon Brown. At the end of the final term all the Year 1 class would put their work up on the walls and he would go around critiquing it. He stopped at one particular piece and said, “Who’s responsible for this?”, and a nervous fellow put his hand up in front of 200 people. Vernon looked at him and said, “Have you tried accountancy, or perhaps the law?” My academic friend said, “If you say that now, (a) you would lose your job, and (b), the course would lose its funding.”

What sort of architecture were you looking at, or were aware of, when you were a student? Modernism would still have been the prevailing orthodoxy?

We visited all of Peter Middleton’s houses, and houses designed by Claude Megson, who was an incredibly controlling kind of architect.We were able to speak to clients about how they got on with their architect. We learned a lot.

I did travel to Australia, and liked the terrace housing there. I liked Sydney. I know there is massive suburbia surrounding Sydney but in the core of the city were terrace houses which I found quite lovely, and a good use of land. One of my jobs when I was at Hamilton Boys’ was mowing lawns and I am pleased to say that since I left school I have never owned a property with a lawn. I haven’t mown a lawn for 40 years. So, I was influenced by Australian terrace housing, which is British terrace housing. I was also in influenced by what was going on in Japan. I was interested in the work of Kenzo Tange and the Metabolists.

Why did they appeal to you?

There was a sort of honesty in the way that elements of a building were expressed. I liked Le Corbusier as an architect because, again, his buildings were legible.You could look at one of his buildings and say, “This is a residential building, or a retail building, or an office.”

To have a neutral building that could be multipurpose – I’ve never had any sympathy for that. I subsequently travelled to Japan, and had a look at all those Metabolist buildings.They were in influential.

When you finished your degree, did you consider staying and doing more study?

I am a bit conservative in terms of moving around. I had settled in Auckland and had met my future wife and made a lot of friends. There are many nice elements to Auckland which I really enjoyed. So I started to do a PhD, and then I realised I wasn’t terribly happy. But there were no jobs in Auckland. Muldoon was the Minister of Finance and the whole of Auckland was in a depressed state in terms of building. There was a joke that Muldoon had big taps on his desk where he could turn the economy on and off.

I had spent some holiday periods – as most students did – in architectural offices, among them Miles Warren’s firm and Calder Fowler in Wellington. So I rang Michael Fowler and asked if he had a job. He said, “I’ve got jobs coming out my ears. When can you get your bum down here?” So that’s how it started.

Did you ever consider working for the Ministry of Works?

No. That was another version of Hamilton. I subsequently had a falling out with the Ministry, over Whakatane Airport. It was at a time when I had a lot going on. There was a huge explosion of work, and many people wanting something that was a bit different. It was quite overwhelming. I should have built up a big staff at that stage but I just continued to do it on my own. I travelled all over the country doing houses and stuff. I became a workaholic and it ruined the marriage.

One day a guy I knew who was a reporter with the Whakatane Beacon rang me up and said the local council was looking for an architect to design an airport building. He said, “They want a building that puts them on the map, like a mini-Sydney Opera House. Are you interested?”

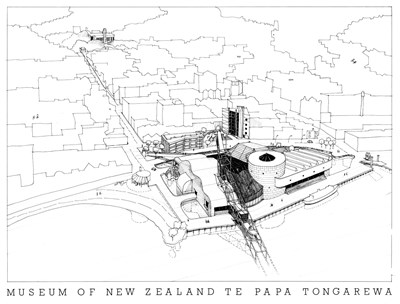

I was up there within hours and did a design – a landmark building, influenced by White Island which is offshore. We managed to get permission to put the control tower on the top of the building, which was unusual. But the Ministry of Works’ government architect, whose name I can’t remember, who had sign-off, said the design was silly and quirky: “Our policy at the Ministry of Works is that regional airports are all the same, so visitors don’t get confused when they go to Tauranga, Rotorua or Whakatane. They know that check-in’s on the left-hand side and the toilets are on the right-hand side.”

I said, “What about regionalism?” “No, we don’t follow that, sorry.” I went back to my clients and they said, “Look, just proceed with the working drawings – we’re in a bit of a rush on this one.” I did, and put the building out to tender. Then the government architect found out and went absolutely ballistic. He called us all to a meeting in his huge of ce in Wellington and said, “Gentlemen, you have de ed my instructions. I don’t know why you are doing this, because the building is never going to be funded. I am never signing it off.”

I remember saying, “Why not? The people love it and it’s exactly what they want.”

He said it would be far too expensive. It would cost $200,000 at least – this was a long time ago. I pushed the lowest tender across the desk to him and said, “Do you think $80,000 is a reasonable price?”, and he said, “That will be a local builder who’s going to go broke. He just wants to build a monument to himself.” Two days later the building was approved. I rang the clients and asked what had happened. They’d called Percy Allen, who was not only the MP for the Bay of Plenty but also the Minister of Works, and apparently he rang the government architect and demanded that either the approval for the building or the architect’s resignation be on his desk on the Monday morning.

For the rest of the time the Ministry of Works existed I was an absolute pariah – the bastard who caused all this trouble.

Whakatane Airport (1971)

Whakatane Airport (1971)

Rewinding a bit – when you came to Wellington to work for Michael Fowler, his office would have been one of the biggest in town.

He was a player. Yes, and of course he became a politician. He was a great mentor. I got on really well with him. He gave me a remarkably free hand given I had little experience.

It was extraordinary, really. You’re not long out of Architecture School and you’re designing the Wellington Club, on The Terrace. How did that come about?

Michael had the commission, but he hadn’t yet drawn anything. He said, “Have you got any ideas?” and I said, “I suppose they want some Georgian thing.” The other partner in the firm, Ian Calder, was responsible for Georgian-type housing in Kelburn. He was old school – a lovely old pipe-smoking fellow. But Michael seemed more progressive, so I said, “Why don’t we put a low-rise building with a residential connotation on The Terrace frontage so it looks like a big house. And then behind we’ll do stage two as a high-rise – a conventional of office building that will generate income.” Michael said that was fine, so I designed the building that was subsequently built.

I never met with the Wellington Club because they were Michael’s clients. I was the ghost writer – he fronted. He had all the skills of dealing with people and persuading them.

Did the building to the rear get built?

No. The tragedy was that the site behind got taken for the Wellington motorway under the Public Works Act, so there was no room to ever build the building. Subsequently that became the kiss of death for the Wellington Club because it was just too small on the site.

Where did this building, and other buildings like the Link Span Building on the Wellington waterfront, come from?

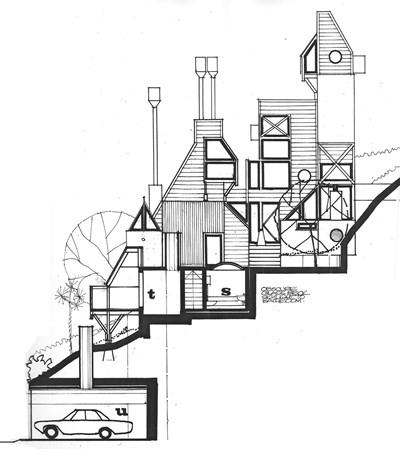

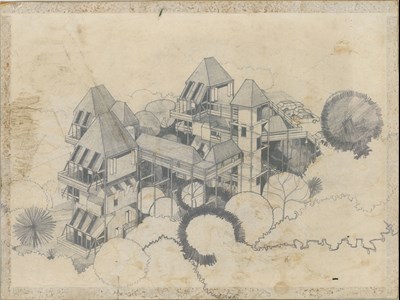

The designs? They were just a distillation of things I had in my head. The Wellington Club was probably quite in influenced by the Metabolists. It had expressed stairways and expressed roofs. It was based on work I had done at university, designs and reading I had done there.Where I was coming from creatively was to break the building down into a series of components.

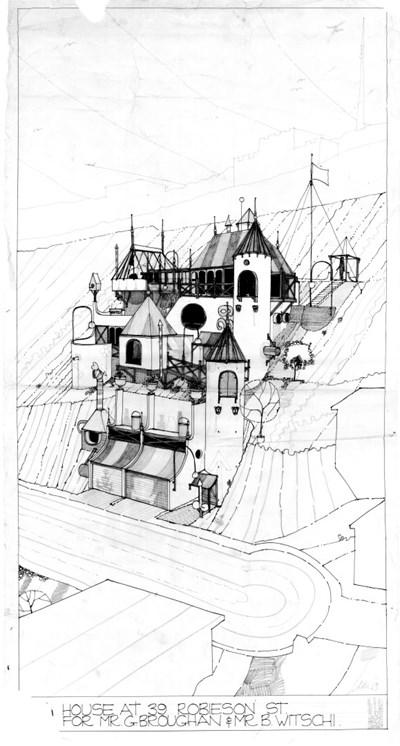

I had this thing about fragmentation and a building not being a simple box. You create a building by providing the spaces that are necessary and linking them in an appropriate way to make them work in terms of a ow diagram, and give them different heights – higher if it’s a major room, and lower if it’s a service room. And then you assemble all those components and the resulting building is organic and probably non-symmetrical. The building is an assembly of all its components, and those components can be read on the outside.

The Wellington Club was a bit different in the sense that I had an instinctive feeling that one day it would be demolished because it was just too small in a growing high-rise environment. So the structure was deliberately overstated.

You were trying to future-proof it against demolition? Again, what is extraordinary is that you had such freedom. It seems quite amazing, considering the nature of an organisation like the Wellington Club and what the city and the country were like at that time. What else was happening in Wellington in those days?

Bugger all, really. Ian Athfield was doing his house on the hill. Was Plischke still around? There was Massey House on Lambton Quay, but it was bland. The main thing about the Wellington Club was that its purpose was fundamentally different to the surrounding of office buildings. Even though it was a club I saw it as a house – there were residential units in there. It was a great opportunity for me to strut my stuff. I was very lucky.

One of the great things about Michael Fowler is that he promoted residential use in the central city. I remember going up with him to the roof of our building, the Prudential Building, and there was a caretaker’s house up there.

You looked down Lambton Quay and most of the buildings in the area had a caretaker’s house on the roof. Our caretaker told us, “I can’t believe how lucky I am. I have fantastic harbour views, I’ve got sun all the way around, the kids have got a roof deck to play on, we can go down in the lift to Lambton Quay.” Michael turned to me and said, “More people should enjoy this way of life in Wellington.”

Michael Fowler’s mana with the people who belonged to the Wellington Club was sufficient for them to trust that what he was selling them was something good. People are often not as conservative as you think.They behave conservatively in groups but get them as individuals and you’ll find out about their funny habits.

Which you must have done through your career... You didn’t stay long at Calder Fowler & Styles?

I had a lot of friends and by word of mouth I had all these commissions to design individual houses. Some of them were in clumps. In Wilton, for example, there were about five in a row. I was doing these jobs on the side, so I was fairly exhausted. I said to Michael one day, “Look, I have to push my own barrow,” which was a decision that, in retrospect, might not have been the right one. Michael, generously, did not tell me to bugger off, but told me I could work for him for two or three days a week and build up my own practice.

Why do you say going o on your own might have been a mistake?

The corporate architect thing has never interested me, but staying with Calder Fowler would have been more financially secure for me. I think that’s what I’m saying. My financial life has been extremely fraught. It’s probably the only thing I’ve got in common with Frank Lloyd Wright, who famously replied to a question about his finances by saying, “I tend to the luxuries of life, and if I do that I believe the necessities will look after themselves.”

It’s probably the only thing I’ve got in common with Frank Lloyd Wright, who famously replied to a question about his finances by saying, “I tend to the luxuries of life, and if I do that I believe the necessities will look after themselves.”

I have struggled financially. My first wife buggered off because she didn’t know where the next dollar was coming from basically – went off with a chap who had a solid job.

In my career, I’ve done too much for too little. I have done schemes out of sheer enthusiasm that I never got paid for because there was no fee agreement. Over the years I have probably looked at people as being more honourable than they actually are. I have learned. I am not like that now.

But is this also something to do with the nature of New Zealand? It’s relatively well-off but it’s not hugely affluent, and it has usually been a challenge to make the case for paying for quality design.

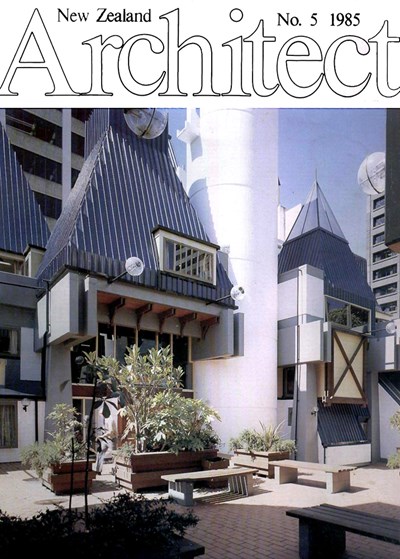

I didn’t ever like to turn work down.When work such as Whakatane Airport and Park Mews [Wellington] and Centrepoint [Masterton, left] came along I didn’t want to tell people I was a boutique architect who didn’t take on bigger work, even though taking on bigger work did lead to a marriage breakdown. In regard to your point about affluence in New Zealand – I had a tendency to get terribly enthusiastic about a project and then it would turn out to be unaffordable, and there’d be an argument about fees. Over the years I have learned to target a design much more closely to someone’s budget.

But in those early years the client would say, “We’d like a study”, or “The kids would like a playroom”, or “Someday we’re going to get another car and so we want a double garage.” I’d say, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” Now I have learned to say, “Sorry but you can’t afford that.” But in those days I just got carried away with enthusiasm.

Who were the people who were coming to you?

They were younger people, and most of them had very little money and relied on Housing Corporation loans. I later met one of the chiefs of the Housing Corporation and he said to me, “I bet you wonder why we finance your houses when they break all our rules about being simple and one-storey high and not having internal gutters?”, and I said I was intrigued about that. He said, “We work on the philosophy that if someone is stupid enough to build one of these houses and they default on their mortgages there will be someone stupid enough to buy it off them.” There was a lot of freedom in New Zealand in the 1970s and the ’80s.There was an atmosphere of experimentation, and not the bloody plethora of rules we have now. It came to a bit of an end with the crash of ’87.

That’s interesting because New Zealanders tend to be very pragmatic and New Zealand has had the conformism of a small society, and yet you and Ian Athfield in Wellington in the 1970s were doing work that was so different. I guess New Zealand was changing quite a bit at that time.

Well, the film industry sort of kicked off then, and in literature we were finding our feet. I remember the famous lines by the poet Alan Curnow, one of my English teachers at Auckland University – “Not I, some child, born in a marvellous year, Will learn the trick of standing upright here.” My parents’ generation went through the Depression and the war and everything was frugal. But in the period we’re talking about – the late 1960s through to the ’80s – there was a cultural blossoming which affected architecture in the sense that there were younger clients who wanted to look to the future. There was a mentality of why not, rather than why. There was an optimism about creating different things. I mean we used to put signs on houses of ours that were under construction saying things like “37 Warwick Street is not just another box”. There was provocation as well.

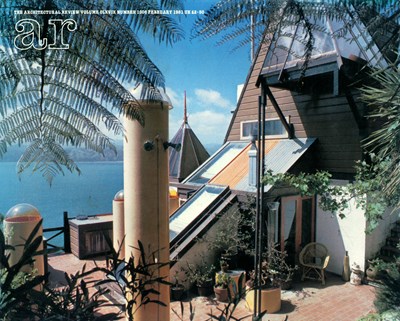

In New Zealand’s architectural history there are moments and movements associated with places. For example, there’s Auckland in the 1950s and The Group, and then Christchurch in the early 1960s when Miles Warren came back from the UK and he and Peter Beaven were working in the city, and then Wellington in the late ’60s and the ’70s when you and Ath were at the centre of something different – all those turrets and gables and round windows. And it wasn’t just house clients that commissioned you. Developers recognised there were buyers out there who wanted something different.

I think New Zealand has always championed individuality, even in the suburbs, which had a negative effect on me as we’ve discussed. You visit parts of Australia and see whole tracts of houses with exactly the same coloured tile and same brick. I think that period, which you allude to somewhat romantically, was a break-out period. We had cut our ties with Britain, and we were on our own.We needed to do something that was expressive of where we were in our culture. Athfield and I were just lucky to be around at that time when that happened.

What were the main differences between your architecture and Ian Athfield’s?

A lot of people talked about us being the terrible twins. I was one of the volunteers who did a bit of plastering of Ath’s house one weekend, but I only actually met him on the first house I did. I went up one night because I was moonlighting – I was at Calder Fowler during the day. It was winter and dusk was falling and there were two shadowy figures on the first floor of this house under construction. I went up and said, “Can I help you?” and one of them stepped forward and said, “I’m Ian Athfield and this is one of my clients and I am bringing him here to show him that there’s another mad architect in Wellington so he feels a little bit less exposed.” That is how we met.

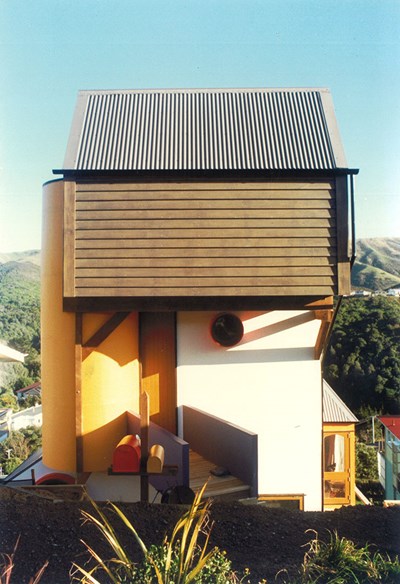

I think the difference was that Ath was sort of hands-on. He also had this plastering thing. His own house – his village – was mono-clad, if you like, with plastered roofs and ceilings. It was very sculptural and referenced the Greek Islands and stuff like that. I don’t know whether that hut in Hamilton was in my head, but I liked the collage approach. I liked creating an assemblage of different materials. Maybe that was the difference. But I think that we were singing from the same songbook in terms of expressive design.

Was there competition between the two of you?

No, but we kept our distance.We didn’t see each other regularly. I was married and because I worked such ridiculous hours, every spare hour I needed to be home with the family to just try and keep things going. We did collaborate on one project through the Architectural Centre, to do a whole lot of funny things at Petone Beach. Ath did an island and I did a wharf. In subsequent years, when we were both a bit more relaxed and I had a slightly better work-life balance, we did socialise a bit. But there was always a distance between us, a respectful distance.

What did you think of postmodernism when it arrived in New Zealand?

Rubbish. I thought it was just derivative. I can see where it came from – the mining of history and all that. I was disappointed, because Miles Warren was a hero to me in those days. Both Ath eld and I worked for him at 65 Cambridge Terrace and admired his and Peter Beaven’s commitment to architecture. But I became disappointed when Miles embraced postmodernism, which became a stylistic sort of perversion – overstated pediments.

What about your Vintage Homes line of houses? Were these houses with their colonial forms a local variant of postmodernism?

I don’t think they were postmodernist so much as derivative. I mean the houses and buildings we’ve talked about were progressive, and the Vintage houses were probably fruitier. I am still doing houses but they are not as fruity – more pared back, yet still with that flavour of assembling different spaces in a logical way.

What are the great buildings that you like?

International buildings? I’ve just been to Holland; I saw Wozoco, an Amsterdam building housing old people, designed by MVRDV. It has balconies all over it, and all different cantilevers, some of them about six metres. Every balcony has a different-coloured glass on it, and different materials. It’s a large, standard, rectangular building with clip-ons. I really love that building.To me it expresses the individuality and the dignity of old people. They’re not shoved into an anonymous rest- home, into a room the third window along on the second floor.

I like buildings that relate to a particular social circumstance. In Japan I loved the Nagakin Capsule Tower in Tokyo. I love Frank Gehry’s work, particularly from his middle period when he wasn’t flying quite so high with the eagles. In New Zealand I like Warren and Mahoney’s early work. I do like the cathedrals in Europe, and I like London. I like Foster’s building – the Gherkin – and the Pompidou Centre because it is made up of components assembled together. I don’t like Palladio. I don’t like symmetry.

You said you treated the Wellington Club as a residential building, and isn’t that true of much of your commercial or larger-scale work? These buildings might have more components but they are fitted together like residential buildings.

That’s a fair comment.

When you started your office you were very busy. Was there a tension already between the volume of work coming in, and what you could control and how you could make a living?

At its peak, there were clients coming in whose names I couldn’t remember.

How many people were working for you?

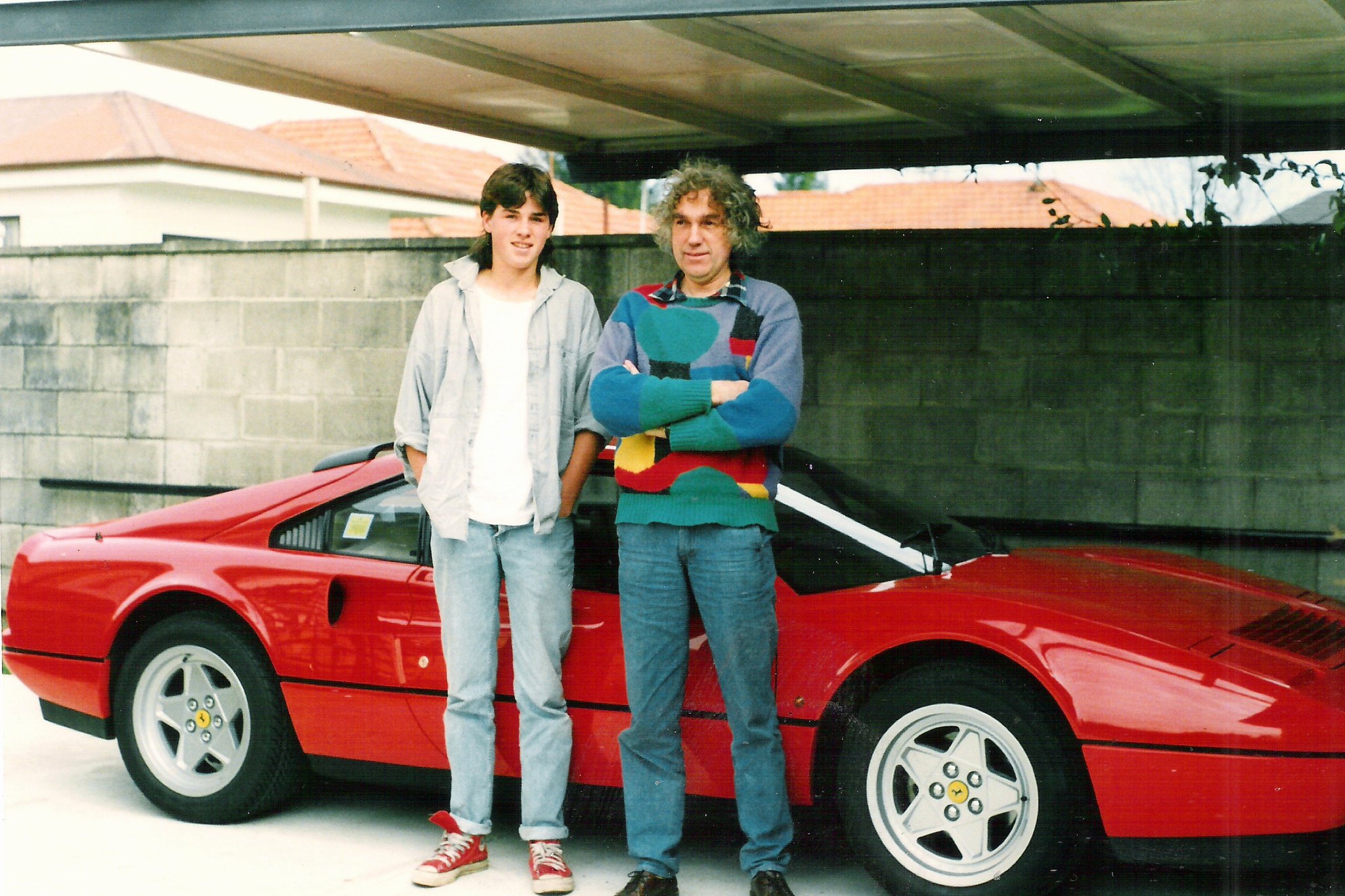

Three or four. The office peaked at seven, I think. We did a project for Foodstuffs in New Plymouth called Centre City. I got a decent fee out of that, and remember the clients were very upset. They said, “Normally, when a job is finished our architect doesn’t go off and buy a Ferrari.” I said, “Well, you didn’t pay me any more than you paid your other architects but I don’t have a glamorous secretary and expensive overheads in my of office.”

Around this time the Wellington developer Bob Jones came to you for a building in Masterton. That seems a strange marriage. How did it happen?

It links back to what I was saying earlier about the yearning out there for different buildings. I think Jones as a businessman thought I had a style that was receiving a lot of publicity so maybe he could do a commercial building and hook into this young enthusiasm. It was a commercial decision on his part.

Because Mr Jones has never evinced much liking or admiration for architects?

No. He threw me out of his car once on the Rimutaka Hill road because I upset him. That was very dramatic. I saw him in 2015 for the first time in 35 years, although he has referred to me in a couple of his books. He had a bit of the Trump in him, and had political ambitions.

No. He threw me out of his car once on the Rimutaka Hill road because I upset him. That was very dramatic.

When we opened Centrepoint Muldoon was his great hero but unfortunately Muldoon was voted out of of office a week or two before the building was due to open. I was the one who had to ring him and ask whether he wanted the brass plaque changed to the Right Honourable Hugh Watt, [Labour Party] Deputy Prime Minister, or did he want Robert Muldoon MP? When Muldoon answered, I had to hold the phone at arm’s length.

Fortune’s wheel turns through all our lives and careers, doesn’t it? In the 1970s your profile was probably highest, and then in the 1980s things changed. It’s a real challenge in life, whatever you do, isn’t it? How do you maintain a reputation or a profile while things change around you?

That’s an interesting question.There is a sort of maturing. Times have changed. My practice hasn’t got the huge pressure of individual houses that we used to have. Our work has moved into multi-unit residential. I think that’s just where the market is at. Things have changed in New Zealand in the regulatory environment.The sort of different buildings that we did are much more difficult and more costly to achieve now because of town planning and building regulations.

The existence of a market of individuals wanting unique buildings was, in my mind, absolutely true. The reason we got Whakatane Airport – it was the only airport we have ever designed – was due to a unique set of people and circumstances. We did a petrol station in Stratford for people who wanted the best petrol station in New Zealand. We did a hotel in Queenstown for THC who wanted the best new hotel.We have done one church in Taumarunui but we have never had repeat business.The only work that has been consistent throughout our practice is residential.

Nowadays – getting back to the mature period, if that’s what you call it – we do a lot of work on the basis that we do a cost-effective job. We have clients who think they’re getting good bang for their buck.

All of Henry Ford’s cars were black – not because it was his favourite colour but because it was the fastest drying one.The other end of the car scale is Volkswagen. Every Volkswagen that leaves the factory is different. They have a system of blending bespoke with standardisation, so you have all these wheel choices, upholstery choices, engine choices, colour choices.You can see that the world wants to buy products at the right price but also wants them to be unique.

Were the Vintage Homes assembled on site or was there a factory?

They were just built conventionally. Factory building isn’t easy – there was a company in Palmerston North that started to do factory-built houses but it went broke. Anyway, the Vintage Homes were just conventionally built, but because they were modular there were cost savings in the standardising of product. The 1.2-metre module was tailored to the width of a sheet of Gib board. The theory was less wastage of labour and materials.

The purpose of Vintage Homes was to try and answer what I saw as a perceived market demand as a fledgling businessman. I hired an ex-Ministry of Education building manager to be my partner and we built up a franchise network.We were doing everything right. (We’d like to resurrect Vintage Homes.) I looked at it pragmatically as a way of doing something architecturally satisfying which I thought was socially responsible, and which would also subsidise the mounting costs of designing bespoke houses. A bespoke build nowadays is probably going to require alternative solutions to the Building Act. It will attract pages and pages of requests for further information from the council when you put in for a building consent.

In today’s environment there is a huge amount of work involved in designing one-off houses, or one-off buildings for that matter. In my mature years I am trying to work with the system. I could have knocked off and said, “I had something to do with the ’70s,” but (a) I don’t have enough money to retire, and (b) I really enjoy new opportunities and new challenges.

And challenges now are mostly in medium-density housing?

Exactly.

And what are the challenges in this field?

I follow the principle that medium-density houses must look like individual houses, and that can be achieved through the collage approach I mentioned earlier. You can have a row of reasonably standardised houses but they can be clad in different materials to achieve uniqueness.

The challenge of multi-unit housing is to maintain the residential values that exist with individual housing so that people don’t feel as though they are compromising the quality of their interior and exterior environment by sharing a wall with somebody else. That is a challenge. The work we are doing in Australia is to do with exactly the same thing – trying to individualise units. The development in Auckland which I really admire, Hobsonville Point, has variety. Multi-unit housing is definitely the way of the future. Sociologically, the three-bedroom suburban house on the quarter-acre section is on the way out.There are so many new demographics – more people living alone, for example.

We are also doing apartment blocks and, again, they are quite challenging. In seismic areas symmetry is required, structurally. The buildings that collapsed in Christchurch had a lift at one end so the floors were sort of swinging around this lift.

So you’re forced into symmetry?

Yes, I’m forced into symmetry.

What about density? Multi-unit housing in the New Zealand context is medium-density, an inexact term. What sort of density should we be aiming at in our cities?

The debate about this in Auckland is quite unclear, isn’t it? To me, it’s just Auckland transforming itself from a large town into a city. I think densification is all to do with the variety of spaces. In European cities people have had apartments for yonks. We still have this extraordinary attitude to density in New Zealand. I’d be reluctant to quote figures but I think in Auckland the density of people per square kilometre is about half that of Sydney and Melbourne. It is about 10 per cent of Mumbai or Singapore, which is at the other end of the scale. So there’s a huge amount of room to move with our cities.

I think what we have to constantly battle with is the popular resistance to change. It’s well known – in planning circles it’s called the Eiffel Tower Syndrome. When the Eiffel Tower was built in 1899 a lot of the artistic community said it was an abomination. One writer rented space at the base of the tower and told the press it was the only place where he could work where he couldn’t see the bloody thing. Now, if you suggested for an instant that the Eiffel Tower should be bowled you would be slaughtered.

So there’s that ‘familiarity’ mentality. We have it with townhouses or infill, where typically a client acquires one house on a reasonably large site, then we put four, five or six houses on the site and then there’s a firestorm of objections from the neighbours. I’ve got a letter on record from a gentleman who signed himself “Patrick Isdoff”. He wrote that “You should know better. An architect of your standing shouldn’t be lowering yourself to designing this horrible crap – shame on you.” I said, “Who is this Patrick Isdoff?”, and started looking in the phone book.Then I realised my correspondent was, actually, “[P]issed off ”

I personally believe that in Auckland the people who have are behaving selfishly. The Nimbies say, “We don’t want a three-storey building next to our house – we’re here and we’re happy and we don’t give a shit about young people or rst-time buyers.We’re sweet thank you very much, so go away and stop changing our environment.” As time goes on I think we will get better at intensification. I really praise the authors of the Auckland Unitary Plan because they have gone against huge public pressure to back off and compromise.

Let’s talk about cars, another long-term interest of yours.

We have talked about a lot of influences and confluences. My upbringing in Hamilton threw up this whole issue of transport. If I talked to a psychologist I would say it was my way of escaping from my straight-jacket upbringing.

By literally getting behind a wheel?

Yes.The house that I was brought up in and in which my parents lived for 70 years was a builder’s special. It was probably designed the night before.The living room cunningly didn’t have any sun or any views. The sunniest room in the house was the dunny. The kitchen was the main entry to the house and it had three doors leading off it, so the kitchen was actually the foyer to the house. My poor old mum had to struggle away with all these people walking through.

So, I got into cycles, anything with wheels just to explore the world – the world being the maximum of how far you could ride in an hour. I was interested in cars because, as I said, I’ve always been interested in industrial design. At school I liked different types of cars. I recognised the hierarchy of self-indulgent sports cars and transport for families. Saloon cars, vans, trucks, earth-moving machinery – they all did something and they all fitted some kind of specialised purpose. I found that quite fascinating. I was then determined to buy a car. I bought my first car off my uncle. It was just a lot of fun. It was fun that you didn’t have living in a suburban house. The car eventually caught fire.

My life started to revolve around cars. At one stage I had seven cars. I’m down to four now. I like the idea of a wardrobe of cars. Do I feel like a sports car today? Am I going to roll up my sleeves – do I need the Ute? I spent far too much money on cars and have lost far too much money on cars.

There is no explanation for why I like cars. It’s only the wheels and the engines and the bodies that appeal to me. It’s true that I fancied a Ferrari and, as said, after I worked really hard on a big job I had enough funds to get one. The accountant actually said to me, “You have a tax problem and what you should do is buy a car and claim the depreciation on it,” and so that is what I did.The Ferrari is 29 years old now. It’s sort of a member of the family.

Do you drive it much?

Once a month, probably. I go to the Wairarapa or take a mate or a friend’s kid around town. It’s not rational to have the Ferrari – it owes me $130,000. I would have been happy being a car designer. I met a car designer on a recent trip to Europe – he designed various Formula One cars, including the McLaren F1. McLaren wanted him to be their full-time chief designer on a massive salary but he told them he valued his independence too much.

Over the years, I have had development clients saying, “We’ll make some space available in the corner of our office for you to do all our work,” and I’ve decided to pass up the lucrativeness – is that a word? – of the offer because I value my independence more than anything else.

I follow the evolution of cars in the same way I follow the evolution of buildings. It is quite clear that building a one-off bespoke house is not going to be affordable for the vast majority of the population, but it will still be a great statement.There is a parallel in the car industry – some people can afford Lamborghinis, but even Toyota, even though its cars are essentially transportation devices, is injecting some personality into them.

What’s the loveliest car?

Pretty much most Ferraris, I think. I like my car – it’s a 328. Ferrari has employed various clever designers over the years. It has the mechanicals, the engine, the suspension and stuff, and then it shrink-wraps the body over it. Everything is very tight – you feel the tautness of the body – whereas American cars tend to be bloated. Barges on wheels. Zaha Hadid designed a couple of cars, and Le Corbusier designed the Voiture Minimum.

Roger and son, and Ferrari

I think there will remain a market for cars where you can actually change your own gears and do your own driving.They will be enthusiasts’ cars. And there will still be bespoke housing. But what I am interested in, for the future, is some sort of modular system which keeps the cost of houses down, keeps their prices predictable, and makes the compliance issues go away.

We got a consent for a house recently which covers 50 houses that are similar. I can see the future of architecture is more in that direction rather than the creative genius waving his ballpoint pen around saying, “I think it should be like this.”

Can we look at popular perceptions of architects. When you started out...

It was glamorous, and it is glamorous. The reason the Schools of Architecture have many applicants is that a lot of parents, and a lot of students, see architecture as partly artistic and partly business. If you say to your parents, “I’m going to be an actor,” or “I want to be a painter,” they’ll say, “You’re going to be living in a garage, and you’ll be up against 27 other people when the one role comes up.”There is more certainty in architecture, and still some glamour.

Mind you, I remember an incident when I was in England, shortly after Prince Charles had delivered his ‘monstrous carbuncle’ speech to the Royal Institute of British Architects. Two or three weeks after that I was chatting up this English rose – I was single at the time – and she asked me what I did, and when I responded she slapped me. She said, “Prince Charles said you architects are all vandals.”

That was a good start. Did you recover?

No, she buggered off...

You have survived a career in architecture with your sense of humour intact.

The one good thing about my parents’ taste in magazines was Reader’s Digest, and the only bit I ever read was an item called ‘Humour is the Best Medicine’. Billy Connolly rang the office once and the guy who answered the phone said, “You’re not really Billy Connolly?” and he said, “I am really Billy Connolly. I’m in Wellington to do a show and I went past that funny building in Hataitai [Park Mews]. I want to meet the architect who designed it because he’s got a sense of humour.”

And so we did meet Billy Connolly. He and his wife, Pamela Stephenson, flew me to Sydney about 10 years ago to look at sites.They were spending so much time on the road in Australia and New Zealand that they wanted a place. They were travelling with three young girls and a nanny and it was costing them a fortune in hotels. Billy is very switched onto design.We found this site but before they put in an offer on it he got headhunted to do a sitcom in the States. But he still rings me up, and every time he comes here we have a back-stage catch-up.

We haven’t really talked about joy, but one of the things about architecture is the joyful aspect. There should be a real, visceral pleasure in looking at buildings. Architecture shouldn’t bring just comfort, but actual joy. Do we live in joyful cities? What do we think about morbid buildings and sterile environments? Are they good for our souls? What is the role and purpose of beauty?

Doctors will tell you that it is good to have a laugh. I met Stirling Moss at the Goodwood Festival of Speed. He’s 90-something in the shade, and all he did was crack jokes. I thought, “I can understand why you have got to a ripe old age.” He doesn’t take anything too seriously.

Do you feel collegial about your fellow architects?

To be honest, I am a bit of a loner.

Yet you’re a member of the New Zealand Institute of Architects and its latest Gold Medallist to boot?

Oh yeah. I’m not antisocial. I really enjoy time with my colleagues, and I love the conferences. I enjoy the big picture but I don’t like spending time with colleagues who grizzle about building consents, or pick your brains about what’s the best type of flashing to put around windows.

I like to spend time with my girlfriend, Moerangi Vercoe, read books and go to movies. I’m really a loner by nature. I think it goes right back to Hamilton days and having to spend time with relatives. I have got an awful number of superficial friends and probably a handful of very close friends. Basically, there is just too much to do.There’s not enough time to do it in.

And the work is still coming in?

Yes, the work is still coming in. A lot of it is not particularly architecturally satisfying.The big avour of the month, or the year, in Wellington is converting redundant of ce buildings into residential use. So we do these Rubik’s cube things and t apartments in. Staff document those, and that pays the bills so I can get on with dealing with the wacky things.

Do you enjoy Wellington? You came here when you were young and you have stayed here.

I wouldn’t live anywhere else in New Zealand. The weather is rubbish, but if the weather wasn’t rubbish it wouldn’t be Wellington. I think Wellington is a nice-sized city. As someone said, it’s big enough to avoid people you don’t want to talk to and small enough to bump into people you know. I like its compactness, and the fact that there are different places and precincts. I like the shapes of the hills, and I like that the suburbs are often separated by a tunnel. It’s not just an amorphous bedspread or patchwork quilt. I like that I can walk to the council and walk to the bank, see a client and have lunch with a mate – all in one day.

My family all live in Sydney. I enjoy visiting Sydney but I could never live there because it seems too Auckland – too big and amorphous. I could live in London as an eccentric old gentleman, going around the shows and galleries, and looking at the latest architecture, but I wouldn’t be happy if I wasn’t designing something.

I am not a conventionally religious person, but I do believe gifts of talent should not be wasted. Billy Connolly, again, says that “we all know nature is essentially beautiful, but the most interesting thing of all is what we humans can add to it.”