Hugh Tennent and Ewan Brown

Michael Moore-Jones in conversation with Ewan Brown and Hugh Tennent.

Michael: Let’s go back to the beginning with your early lives and paths to architecture.

Hugh: My upbringing was a suburban one, both parents having come from farming families in the Manawatū and Hawke’s Bay. I lived in Dunedin and Wellington, went to school in Nelson, then university at Victoria and Auckland. Architecturally, I had an interest early on. I remember spending a lot of time as a kid, probably not over the age of nine or 10, drawing houses, using a book on American ranch houses. I sort of knew I wanted to be an architect by the age of about 12.

I went to Raroa Intermediate [Johnsonville], and the art teacher Neville Porteous had a house by Ath [Sir Ian Athfield]. I remember going to his house and was completely struck by the fact that when you walked across the living room, you looked down over the toilet, and it was all open like a mezzanine. It was the 70s, quite reactionary and free spirited. It struck me as being wonderful, that house.

Through secondary school, a boarding experience, I had an inclination towards architecture. My mum’s cousin was Michael Fowler and she asked ‘What should Hugh do if he’s interested in architecture?’ He said, ‘Just get him to draw and photograph things and don’t worry about tech drawing’.

Above: Porteous House by Athfield Architects, Khandallah, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, was an early influence for Hugh. Photograph by Tony Athfield, AAL Archive.

Ewan: My background is quite different. I grew up in Palmerston North and stayed there until I left for architecture school. I grew up in Milson, in a little house with an outdoor toilet, between the rail line and the airport. My father was a builder – a very basic builder, I never saw drawings – and my mother was a nurse.

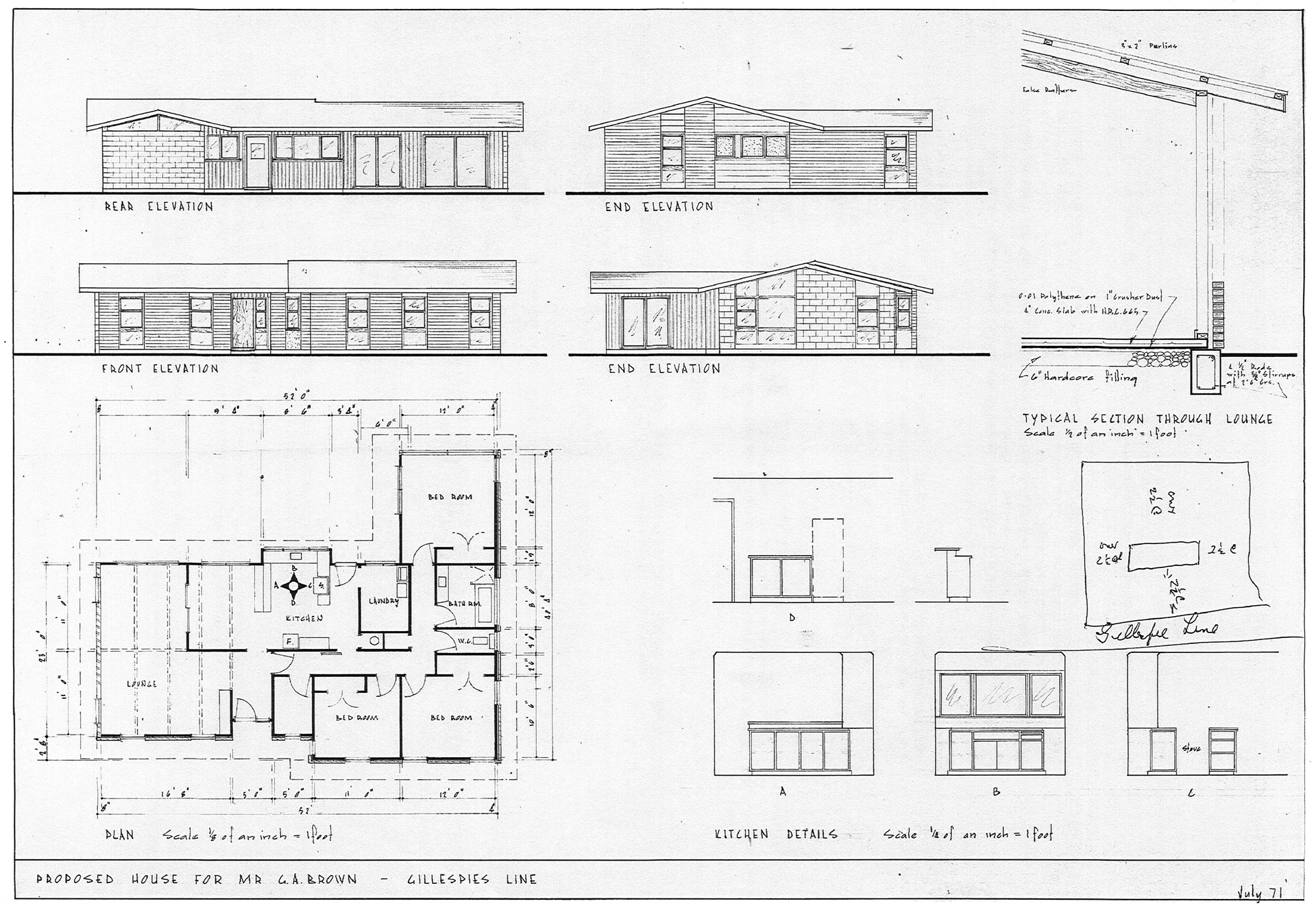

Aged 10, my parents bought 10 acres of land outside Palmerston North. It was about 1972, there was a recession, Dad had no work, so he built our house. He designed it as well. It was quite modern – vertical panels of block with vertical panels of glass, a skillion ceiling, L-shaped and sheltered from the wind. It was very simple and I didn’t think of it as architecture, it was just home. I didn’t know any architects, didn’t know any other builders, so it was unusual that in my first year of college I decided I wanted to be an architect.

From about the age of 14, I worked for Dad in the holidays and did other jobs with farmers. Mum was a nurse, so there was a lot of caring in her world. We were in Kairanga, away from town, so there were lots of community events. I went to the local school, then to the local boys’ high school. I did a year at Massey, then moved to Wellington to do my architecture degree. I hadn’t travelled – hadn’t been to Auckland – and it was a big, big mission coming to Wellington.

Above: The house that Ewan’s father built. Photograph by Ewan Brown.

Michael: How would you describe your architectural education? Which teachers have stuck with you?

Hugh: My first year at Victoria was completely devoid of architectural conversation. But I do remember going to a meeting in Khandallah with Ath and Roger – pretty drunk, very colourful. It was fun, they were free spirited. After that, I went to Auckland University. I think of many people like David Mitchell, Mike Austin, Nick Stanish, Russell Withers, Rewi Thompson. They were practitioners and teachers in our studio who were concerned about social, poetic and cultural aspects in addition to the technical. They were good influences.

After a couple of years, I got tired of being educated and took two years off to go building with a friend, John Constable. We had a truck and tools and taught ourselves by doing small contracts. It was a great way to understand the physical reality of what we were drawing. Towards the end of that period, I started developing an interest in Buddhist thinking and went to Southeast Asia for a year, which led to deeper inquiry – the realisation that there’s more to this life than just the things I had encountered.

Ewan: I didn’t find any teachers particularly inspiring. The school was best for making friends, many are peers now. The best thing was Russell Walden’s history of architecture. Russell was a real character, which made his classes memorable. The real teachers came after architecture school, working under Gordon Moller. And then, of course, a lifetime with Judi [Keith-Brown] as we both trained, started working and did the hard mahi to get lots of experience. Travel was also a teacher – we travelled together to many of the world’s great architectural masterpieces, which is the best ongoing education in my view. Working in Scotland for three years taught me about my family history, and how architecture is made in another cultural context, in a different climate, with different materials. It helped us define what living in Aotearoa meant for us. The last two decades working with Hugh have also been the best teacher – comparing, discussing, editing and growing.

Michael: How did you find your early work as architects?

Hugh: When I came back from Southeast Asia, I discovered that there were monks – Westerners – living in Wellington, on Glenmore Street, near the Botanic Gardens. They were from the same order as the monastery I had stayed at in Thailand. They found out I was an architecture graduate and asked me to help them. That’s when I started working on the monastery in Stokes Valley. They had just acquired the land, and Bill Alington – another lovely figure in Wellington architecture – had done a building out there.

The community was looking to build a bigger meditation hall and it was a project that married my interest in architecture with my engagement in the Buddhist monastic tradition. I had some really good help from

a guy named Neil Kirkland, an architect who went on to have a career in the film industry. He was a wonderful vernacular architect and a mentor on that project. It was essentially a small public building, and it felt like the first significant thing I’d designed. I also organised the building of it, which was very rewarding. There was a strong sense of community – almost like a barn-raising – with support from different Southeast Asian people, including Thai, Lao, Burmese and Sri Lankan.

Ewan: I worked for a year at Jasmad, then went to Craig Craig Moller [CCM] for a number of years and got registered before I went to Glasgow, where we landed in a recession. Judi worked in social housing and I worked in commercial companies, then had a great experience on an international competition. On our return, I worked for CCM on the Wellington Airport project. I’ve been in a few practices where some things fit and some things don’t. You never doubt what you’re doing, but at certain points you wonder, ‘Why are we doing this stuff?’ I found I enjoyed working in teams rather than being alone, which you can only figure out by doing.

Michael: How did life bring you together? What did you want in your own practice?

Hugh: I had my own practice and had only worked for Structon Group for a year. I registered through a mentorship pathway. I was probably a bit of a fringe dweller, in terms of being interested in this meditative thing and building. After the monastery, I moved into town and set up my own practice, mainly doing houses. It was the early 90s and there was a bit of a recession. I built up the practice, mainly doing residential and some education work. I ended up working with Bevin Slessor on a new school for Seatoun.

I felt a bit lonely in the sole-practitioner context and thought it would be good to have someone to work with. I was living up the coast with a young family and walking from the railway station to my office near Courtenay Place when I bumped into Ewan. We chatted and then bumped into each other again a few months later. Eventually, he came and worked with me. Very quickly, I realised I didn’t want him to work for me, I wanted to work with him. I wanted him to really invest his mind and energy into the practice. There were areas where I was strong and areas where I was weak, and he was very strong in many areas where I wasn’t. As soon as we got together, we started to build capacity with bigger projects.

Ewan: I had made the decision to leave CCM and realised there were only half a dozen jobs in town I wanted and called those particular firms. When I ran into you [Hugh], I wasn’t thinking about working with you specifically, but I casually mentioned, ‘If you know of anyone looking for someone like me...’. Then Hugh rang me and the timing was perfect. I remember making a list of notes, about 10 things, which I still have. The conclusion I came to was that I had managed to change most of the things in the firm I was with, but you can’t change the directors! I decided you have to do it yourself – be part of a young, growing and positive firm, having fun, with a good team, shared goals, integrity, and a focus on continual improvement.

Michael: How did you build the practice and do the kind of work you wanted?

Ewan: Early on, Hugh and I realised – maybe without fully understanding ourselves – that we enjoyed projects with a community focus. It wasn’t about architecture for its own sake, it was about the impact that buildings can have on people.

Hugh: I think of it as architecture that uplifts, not just economically for the client, but socially and culturally. We’re drawn to projects with a social aspect, something that does more than improve the bottom line.

Ewan: The key takeaway from my earlier experience was realising how a small, skilled team can run large projects. With Wellington Airport, there were only five or six of us running a $100-million project. That was transformational – being in the flow of a high-performing team, both in the office and with a team of great consultants.

Hugh: It has become a theme. We punch above our weight in terms of the scale of the projects we can handle, while keeping the practice relatively small. Maybe we could have more people who are really keen on leadership and business development and pressing the flesh…

Ewan: …but we haven’t wanted to grow for the sake of growing. I love having a small, high-performing team. We’ve learned that you can do almost anything, even without prior experience in some areas, by approaching each opportunity with a focus on doing it really well. Growth is a series of taking opportunities and doing the absolute best you can. That means designing, documenting and running the project well on site. Leaving the client as a fan at the end of the job is your best form of advertising. This approach has allowed us to make jumps in scale, establishing ourselves, then taking on the next challenge.

Hugh: To take on larger projects and a wider range of work, you need a good office. We’ve never been just a design-driven house. You also need a strong client base to sustain you through the ups and downs and building that capacity was key. It’s not just about two people focused on design, we’ve taken care and thought about how we function as a practice.

Michael: Do the business challenges of running a practice interest you, or are they just necessary in service of the end result?

Ewan: At certain points, I’ve buried myself in things that I didn’t enjoy because I thought the goal for our community was to do our best work, and to do the best you have to be really good in all these areas, even if you are not interested in them. I’d worked at firms where I’d seen someone do amazing designs, which hadn’t been followed through – what a missed opportunity! It’s because they only wanted to do the fun bit. It’s about being a sustainable, high-performing business so you can continue to do what you love and do it well.

Hugh: My observation with you, Ewan, is that you do those things that wouldn’t necessarily be recognised as interesting, but you know they have to be done. There’s that sense of serving the practice but finding innovative ways to do that, which is a great attribute. That’s the business side, but there’s also the quality of documentation and ensuring the outputs meet a high standard. I think that’s key. There’s an equal focus on making sure the delivery is as good as the initial idea.

Michael: When did you bring te ao Māori into your lives and work? How has sustainability, which is key in so many of your projects with Māori clients, developed alongside that?

Hugh: When Ewan and I got together, one of our first major opportunities was a proposal for a Māori school in Palmerston North [Mana Tamariki, 2006]. It was a big leap, as we hadn’t really had much contact with Māori communities before then. You often see a lack of direct engagement across cultural lines in New Zealand. They could see from the monastery that we understood the world of wairua.

The project marked the beginning of a journey with te ao Māori, and with a range of consultants who were brought into those collaborations. We were welcomed and supported by the leaders of Mana Tamariki and the project led to many others. For example, one of the parents at the school, Meihana Durie, led to us being asked to pitch for Te Wānanga o Raukawa at Ōtaki. Working in these contexts was so enjoyable because the people were so welcoming. We were educated by Māori. I vividly remember early experiences, such as being mentored by Bob Jahnke, who was leading the Māori Studies Department at Massey University. He was an established artist and mentored us on tikanga and design.

Ewan: He was quite clear when we were getting things wrong, like when we placed certain spaces on the wrong side of the building according to tapu (sacred) and noa (common) principles. We had to learn to get those things right. It was a formative project in so many ways for both of us. For me, there was a personal connection as well as my dad lived just a few blocks away. Even though he was quite frail and had Alzheimer’s, he would walk to the site most days and look at what we were building. When he died, a teacher from the school I had worked closely with did a moving waiata at his graveside.

I had grown up in a largely Pākehā environment, only had one Māori friend at school and never heard the language spoken in my daily life. Then, suddenly, we were in a situation where there was only one room in the whole building where we could speak English, and all we could say was ‘kia ora’ to the kids, who were already advanced in their reo. It was a real eye-opener and a positive challenge. We did a series of training sessions with some of our collaborators, which helped us find our way with te reo Māori.

Michael: When did your Living Building Challenge (LBC) work begin?

Ewan: The introduction to the Living Building Challenge came from Jasmax, who won Te Uru Taumatua, which we bid for. Even though we didn’t win, it marked the start of a really rewarding, ongoing relationship with Tūhoe. They wanted LBC principles integrated, first on the Waikaremoana visitors’ centre, then Te Tii in Ruatāhuna.

Hugh: I find it compelling that the high-end sustainability effort in New Zealand is largely driven by Māori clients. As a culture and people, Māori are inherently values-driven and typically deeply committed to kaitiakitanga, the guardianship and stewardship of the environment.

Ewan: The first carbon-related project we worked on was Ngā Purapura, which was primarily focused on health and wellbeing, a physical manifestation of Meihana Durie’s thesis. Next, they had a library burn down, so we built a temporary library. Then we moved on to a lecture theatre, Te Ara a Tāwhaki. With these smaller projects under our belt, we began introducing LBC principles more formally in the bid for Te Ara a Tāwhaki. When I first pitched the idea, I didn’t know as much as I do now, but it sparked the conversation. When Pā Reo came along I presented it in more detail. I realised we had to do intensive materials research, which was very scary. Now, we have a massive spreadsheet – 50 sheets, 2550 lines, each one representing a product researched for 30 different parameters. That’s 75,000 data points. It’s a huge undertaking.

Hugh: The big picture is that it makes buildings healthier and influences the industry. When you call someone – it could be in Russia or Germany, or chemists in Belgium, or a local supplier – and ask if they are using chromium six (which is highly toxic), they often start to consider moving away from harmful materials. In New Zealand, we’re behind in terms of chemical safety compared to the United States or Europe.

Ewan: It can be a huge challenge to achieve the materials petal [one of seven performance areas for certification]. But when someone says, ‘This is stupid. I’m not doing it’, I just say that we’re building a best-in-class project and they don’t have to be involved. That fear of missing out often convinces suppliers to change.

We’ve sort of fallen into LBC. It started with Tūhoe, then we introduced it to Gisborne Airport and offered to do the materials research for free. On Pā Reo, the client team fully engaged with the concept. Ngā Mokopuna was a competition and, having worked on about 100 small projects at Victoria University since CCM, we managed to win it with our LBC experience.

Hugh: Look, it’s not for everyone, because it’s so challenging…

Ewan: …but for the ones who persevere, like the Wānanga, it’s really rewarding. It’s also about being responsible to the future of the planet and our people. And elements of it are for everyone.

Michael: How has your thinking about sustainability evolved with those projects?

Ewan: Sustainability has progressed slowly for me, becoming less fringe than it was 20 years ago. A goal has been to make sustainability more mainstream. It shouldn’t feel out of place on a commercial project. Despite being seen as extreme, LBC is starting to accomplish that. Ngā Mokopuna at Victoria University is a mainstream commercial project, built by a mainstream contractor, for a mainstream client who has accepted the challenge, and it will be one of the most sustainable buildings in the country. It will be one of only 32 to have full living, petal and core certification. In terms of sustainable design, one of the best things you can do is to work with an existing building. People are prepared to work hard to keep beautiful buildings, for example, Athfield Architects’ Te Matapihi Ki te Ao Nui, Wellington Central Library, or our own workingman’s cottage.

I didn’t come from this background when I started with Hugh. He was already seen as a sustainable architect. My concern was that he was seen as fringe – he’d worked on a hay-bale house and was doing a monastery at Kopua when I joined! I was used to steel, concrete and big commercial clients and contractors. As we worked together, sustainability kept coming into the projects. Early on, people would ask, ‘How did you get these projects? How do you force people to do this?’ We don’t force them, clients come to us. We might push them beyond their comfort zone, but we’re not telling them ‘You must spend your money on this’.

With each project and through intensive research, I’ve seen how we can make a difference and how much we have to do. Buildings are responsible for 39 percent of greenhouse gas emissions globally. It has amazed me that a couple of projects – Pā Reo and Ngā Mokopuna – can make such a difference. Everyone working on them takes learnings to their next projects. I’ve also noticed a paradigm shift among a growing number of younger architects, graduates and students wanting to find sustainable ways to design buildings and improve human wellbeing. I recently gave a public talk on carbon in construction and the average age in the room would have been under 30. Graduates want to work with us – they value the integration of sustainable design in our projects.

Michael: Thinking about Te Wharehou o Waikaremoana – Te Kura Whenua, was it daunting building on land weighted with such history? Was it daunting as Pākehā?

Hugh: Working with Tūhoe was an extraordinary experience. It all comes down to the people. Ewan and I went there, we were picked up late at night on a flight to Rotorua and driven quite a distance through Te Urewera, and then to Tuai...

Ewan: …Quite fast!

Hugh: Ewan was just holding things down… and you come around a corner in the dark and there’s a horse and a cow on the road, all really vivid under the headlights in those misty yellows. We met the whānau and talked with them. They informed the design, wanting it to be a softer, non-urban building. The next day we went to another hui at Ruatāhuna. I did a mihi and one of the leaders commented and laughed. I later found out he’d said, ‘Can you stop this guy? It’s like fingernails down a blackboard’, referring to me trying to speak te reo Māori. Fortunately, I didn’t know that at the time. I would have been crestfallen.

There was also the issue of the removal of John Scott’s Aniwaniwa visitors’ centre. It was very salient for us to be on Tūhoe’s team. We got to hear about their experience.

Ewan: It was clear how badly things had gone historically, and we brought it up multiple times, but it was always a very difficult conversation.

Hugh: You have the lovers of John Scott’s work, and, of course, Jacob and the Scott family who are legacy holders for this wonderful architect and free-spirited person. It reminded me of what would happen when ministers went to Tūhoe – they would be hosted by the whānau, told everything, and they’d get a clear sense of the shit that has gone down, the confiscations, the shrinking of their rohe, all the burdens and struggles. Then, the ministers would go back to Wellington promising change. And nothing would happen because once they got back, it was like stepping into a different world, with different mindsets – uncaring and resistant. There was a huge chasm between what was experienced up there and what played out politically.

That’s how it has been, all the way through from the John Key era to the police raids in Ruatoki. It’s the same story time and again. You have this heightened fear from officials, like some police commissioner getting spooked, and they send in teams with rifles, confronting kuia and tamariki with machine guns. It’s unbelievable. You get a feel for the deep mistrust and disconnection. They’re seeking to uplift their people and do things differently from DOC or the way it has been done historically. I understand that now in a way that would be hard to grasp without the contact. Those themes have become part of our architectural practice and life.

Michael: Where does design sit, for you, within these themes and experiences?

Hugh: Some of the things I learned in architecture school were about design outcomes for people, especially in the 70s and 80s, before postmodernism came along with its language-focused approach. It was about how design could be expressive, rather than strictly rationalist. It was post straight-modernism, which can be an incredibly elegant approach, but I was interested in buildings as communicators, and buildings for people.

For me, the defining thing about design is that it’s phenomenological, or experientially driven. It’s thinking about the experience of the building, rather than just its image. How does it feel? How do you experience it in a haptic sense and across all the senses? It’s engaging the five senses and the mental and emotional aspects. I think that has a lot to do with the meditative journey and unpacking the human experience in a more substrate or elemental way – not so much design as an intellectual exercise, but as a felt experience, a whole-body experience. The design drivers are around how a building will be experienced. What’s it like sitting in the corner of this room? What’s it like approaching the building? What’s it like engaging with it?

With that experiential focus, another key idea is that everything in life is interconnected in ways that are not necessarily known. That’s where sustainability comes in. It’s not just about adding a feature onto a building; it’s about understanding where the materials come from, where they’ve been mined and how much energy they hold. This awareness of interconnectedness, culturally and environmentally, is important to us. We like projects that uplift people because we see that buildings are interconnected with people, and people with buildings, in a way that ties into their culture, community and environment.

Ewan: You can’t just separate people, culture and care from the design process. My own design philosophy centres on the belief that architecture can foster cultural connection and environmental stewardship.

Hugh: While each building has its own unique feeling that arises from these principles, there’s a unique expression as a response. Each project is a beautiful opportunity, even when there’s doubt. There’s always some uncertainty. Are we doing the right thing? Is it stretching enough? That’s the wonderful thing about this vocation. It has also become a lot more collaborative, especially with co-design in the Māori context.

Ewan: As I’ve evolved through projects, I’ve found traditional beauty – the aesthetic of a building – can be illusory. Can it be beautiful if it doesn’t respect and reflect the culture it sits within, or if it’s poorly planned? I’ve seen many international examples. And can it be beautiful if it doesn’t have climate-friendly materials or drive towards carbon neutrality, as I think every building must attempt to do. Can it be beautiful if materials have been sourced in exploitative ways, can it emit high levels of VOC’s, or use considerable resources in its creation? Further to that, are staff treated well, do the consultants treat their staff well? Buildings have a significant impact and we have to satisfy all these aspects to be beautiful. It’s a bit like Te Whare Tapa Whā, the wellbeing model designed by Sir Mason Durie, that we used on Ngā Purapura. All sides of the house have to be strong to support the roof of health – the walls are physical, spiritual, family and the world of ideas. The same applies with design or architectural beauty, all these factors need to be strong and in balance to support the roof, which in this case is design and beauty.

The design I enjoy brings together all these issues. Through this sometimes-invisible journey we get to create buildings that become educators, the third educator. After the teacher and parent, the teacher is the buildings we inhabit.

Michael: In 2024, where does beauty fit in thinking about architecture and design? Sometimes the word can feel too luxurious.

Hugh: Beauty uplifts the human spirit. It’s something I’m really focused on, in the sense of proportion, materiality and arrangement. As a species, we sort of churn through things – there’s so much waste in the way we operate, yet so much growth. And I think our design work does incline towards trying to make things not showy, not fractious, overly dramatic or temporal, but something simple that still uplifts the human spirit. If we’re going to build something, let’s do it right. Let’s make it last and make it something that uplifts the people using it, even if it’s in quiet ways. It doesn’t need to be loud. Things that are more lasting are more interesting.

Ewan: If you can combine sustainable design and beauty in a building, it will be loved and fit for the future, it will change and adapt with time for different uses and people. Isn’t that the best way to design?

Michael: What about beauty in the residential context?

Hugh: We did a lot of residential early on – high-end residential and alterations, hundreds of alterations, especially when times were tough. In those projects, we often respond to the protagonist, the client, and what they need and want. It’s also about grounding the project in place – not just in terms of performance and sustainability, but the poetic. It’s a response to the local, a sense of it being grounded in place while also saying something different and new about that place.

We’ve recently done a lot of social housing, which is architecture with a little ‘a’. We strive for good urban design in this space, to uplift the outcomes for the tenants. For instance, we’ll argue about having an extra toilet, or bigger showers for larger people. I’ll go to the top of the local Kāinga Ora to try and influence the restrictions, as they often use standard components that are not appropriate for all people.

Ewan: The social housing projects have been rewarding because it keeps things real. It offsets working on a big house or a high-end commercial building. It makes you realise that a small amount of money can significantly improve a family’s life. You’re potentially affecting the lives of over 50 families.

Michael: How have the directions the practice has moved in developed and changed over time?

Ewan: We consciously took on social housing work and decided to keep doing it. It’s good sense for an office to have a variety of projects.

Hugh: It’s also a reflection of our wonderful principal, Kevin [Lux], who is very capable and instills confidence in the people he works with.

Ewan: It’s good to create a platform where other people can springboard off what has been built. You create something highly functional, small, without lots of layers of management, but with high-performing individuals who work really well together and in their own way. Whether it’s Kevin or others, it’s about grabbing their interests and giving people some autonomy and responsibility, so they can lean into projects and grow in a place where they feel they belong.

Hugh: It’s about keeping the practice healthy. I’m 65 and down to four days a week, so it’s important that people feel like they have something to take forward.

Michael: What else does the ‘health’ of your practice look like? What would you like the next 10 years to hold?

Hugh: One of the things that’s really important is creating a place where people feel connected, like whānau, and care for one another. Those are really important values for us.

Ewan: We also try to keep an eye on churn. Over 21 years, we’ve had 57 employees, and 15 are current staff. In terms of the future, I’m passionate about normalising sustainability and carbon-conscious design. I want to be able to look my kids in the eye and say, ‘I did something’.

Hugh: It’s about leaving a really good, healthy and nourishing legacy for the people we have and the work we do. That’s of primary importance.

Ewan: Making sure the team goes in the direction they want to go, and leaving them operating well so they’re fulfilling their dreams. It will be interesting to see how they adopt the themes we’ve talked about and carry them forward.

Michael: Who has been key to you both on this journey?

Hugh: Nick Bevin has been a colleague and a wonderful support. I remember Nick bringing his kids up to the monastery when we were building it. We went through architecture school together in Auckland. He’s a really thoughtful practitioner of Wellington architecture, a kaumātua of architecture. We have a support group called the Loos Group, a really collegial network of architects, even though we’ve often competed professionally.

We’ve had amazing collaborators too, like Rawiri Richmond at the Wānanga, who has been a fantastic client representative, and it has been nice to work alongside people like Meihana Durie, now the Deputy Vice-Chancellor Māori at Massey. Meihana invited us to bid for Ngā Purapura and we won. He’s been a big part of our story. And then there’s Gordon Moller, a kaumātua in the background since I worked with him. He’s a really generous man.

Ewan and I have had the support of incredible partners: Susie, my wife. And Ewan’s Judi, who has been a powerhouse for architecture in this country. She did a fantastic job as President of the Institute. I have a lot of gratitude for the support and patience of Susie and our family. There’s a fair bit to tolerate being alongside an architect.

Ewan: Judi has been such a strong advocate for the profession. Having that shared foundation at home has been invaluable. There’s been a journey through architecture together – learning and bouncing ideas off each other all the time. Maybe Judi gets a bit sick of it, but there has always been collaboration behind the scenes. It has been a great journey working with Hugh and having Judi in her own sphere. And our sons... well, we probably should ask them what they think about architecture because we’ve certainly spent a good amount of time over the last 20 or 30 years focusing on it!

Michael: What does the award mean to you?

Hugh: I’m grateful to receive this award together because it points to the truth of the situation, which is that you don’t do it on your own. It’s not just about design, it’s about interconnecting with people and the many complex layers that go into creating good work today.

Ewan: We’re really proud of it. It’s about all the aspects that go into making architecture. Ngā Mokopuna and Pā Reo projects feel like the culmination of one journey, but also the beginning of a whole new journey for a lot of other people.

Hugh: In terms of the broader context, there’s a cyclical nature of politics – a flip-flop between progressive and conservative. Personally, I think we need to keep pushing for growth in response to… well, you could say the mess we’re making. We need to evolve and progress as a society, as a profession and as a species. I do hold some quite big fears about the change that’s coming and ecological overreach. Like Ewan has been saying, our response is to do what we can, given the role we have.

Ewan: I don’t often look back and this has been an exercise in tracing threads. Now it’s a question of what’s next. What’s the next thing to tackle? I need to start planning the next 10 years!

Michael Moore-Jones writes about architecture, cultural history and art. He received his PhD from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington and studied art history at Oxford University. Most recently, he was the Day Fellow in New Zealand Art History at Te Herenga Waka.