Mine is not a standard architectural career. My practice has been based in universities and communities rather than offices or construction sites. Thirty years ago, I entered into a field that was without precedent and, in collaborating with others, have built it into something that is meaningful and connected to a rich tradition of building that we know today as Māori architecture.

Kaupapa (foundation)

My career started in the early 1990s during a surge in new research and teaching about Māori culture, led mainly by educationalists, social historians and anthropologists working with Māori: Judith Binney, Roger Neich, Anne Salmond and Ranginui Walker. My whānau’s Rātana Church connections left me curious about the origins of its distinctive Romanesque temples. This motivated me to write my undergraduate master’s and PhD theses, and publications with Bill McKay, about the whakapapa (layering) of social, political, spiritual, art and architectural influences on Māori architecture between 1850 and 1950. These influences include Rātana, Kīngitanga, Pai Mārire and Ringatū architecture and the kāinga (settlements) of Parihaka and Maungapōhatu, as well as the revitalisation of the whare whakairo (carved meeting house) led by Sir Āpirana Ngata and Te Puea Herangi. From this kaupapa, I have been fortunate to establish a career in

Māori architecture, contributing through teaching, research and collaboration to its story, the (re)indigenising of cities and spaces, and tribal aspirations.

(Re)indigenising Cities and Spaces

Māori technologies are an important but under-appreciated aspect of our built world. Our metaphysics explained in ancestral narratives, particularly those about natural forces, inform the physics of customary building. The technologies are continuously expanding to encompass new materials and systems that meet Māori needs within a tikanga-based cultural framework. Art galleries, museums and art festivals might seem unusual laboratory spaces, but working with Māori visual artists in these places provided an almost unbounded opportunity to (re)create Māori architectural spaces using digital means, a radical idea 25 years ago.

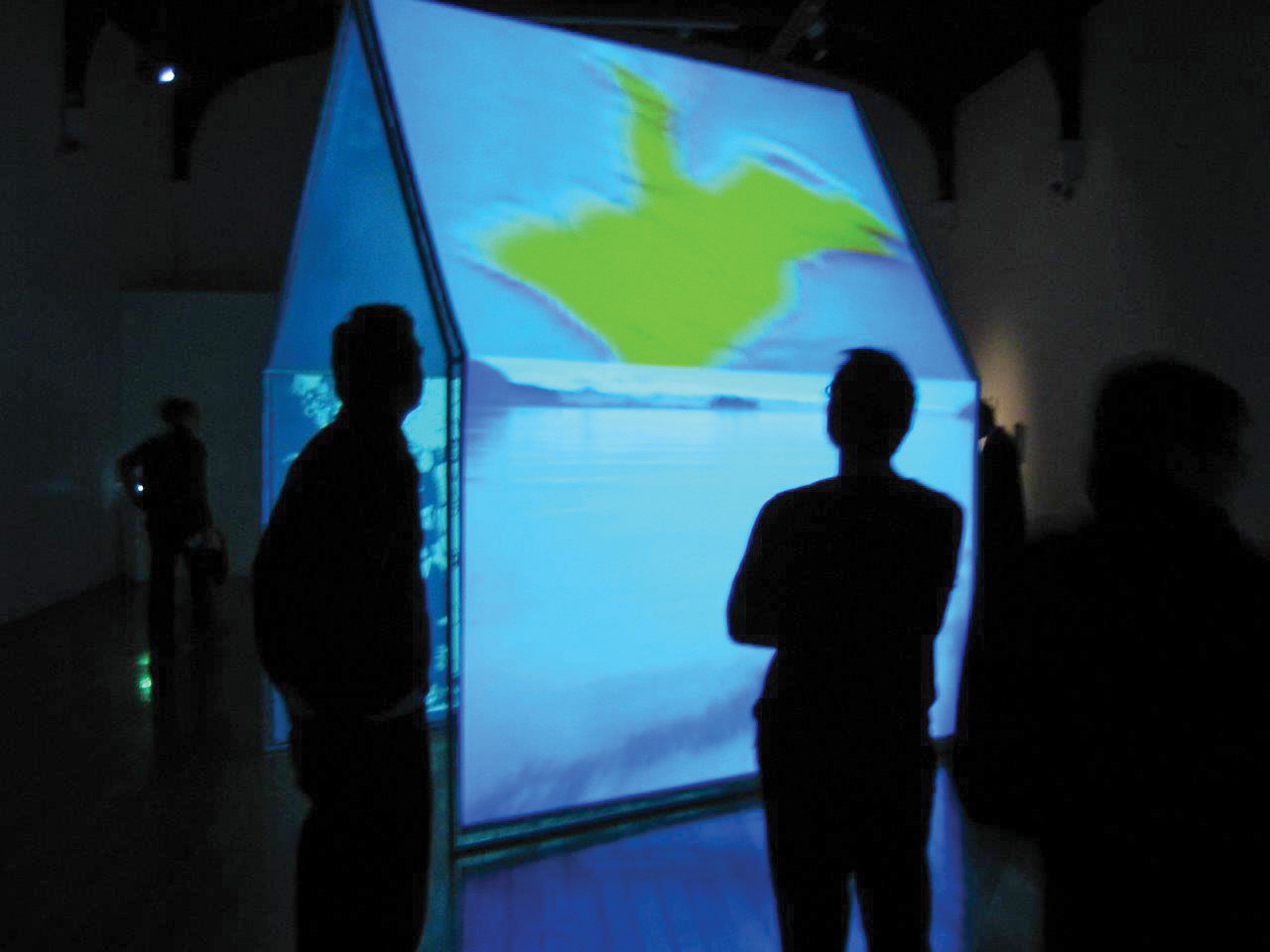

I was appointed to teach Māori art history at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts in 1998. My arrival coincided with the Ngāi Tahu and Crown Deed of Settlement process and a new millennium, both of which stimulated the contemporary Māori arts scene in the South Island. Working in the visual arts surrounded me with cutting-edge Māori artists using digital or digitally inspired means to articulate politically charged ideas about culture, gender, sexuality and politics. The conception and curation of exhibitions were my attempts to install and later project contemporary Māori art onto architectural structures to create new places, starting with gallery spaces Hiko! and Techno Māori in 1999 and 2001, then Whare in Christchurch, 2002, and Adelaide, 2004, and finally on the scale of the CBD with Lightscape in 2004. The artists I worked with included Darryn George, Lonnie Hutchinson, Rachael Rakena and Keri Whaitiri [a list of collaborating artists and curators is available under Selected Projects, page 46], who have continued to collaborate with architects and urban planners on the post-2011 Christchurch rebuild and other city projects.

Virtual and augmented reality were in their infancy in the early 2000s. Working together with the University of Canterbury’s Human Interface Technology Laboratory and Canterbury Museum, we created the first digital avatar of a taonga Māori (a whalebone patu, or cleaver) and later collaborated with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Rakena on an augmented reality mihi whakatau (welcome) for visitors to the museum’s Māori gallery. These new realities offered a way to (re)indigenise urban space, enabling a Māori world view to be brought to life anywhere. They are also fraught with cultural property issues arising from the risk of misappropriation. My publications from 2006 to 2012 on the protection of cultural property related to Indigenous digital avatars and environments are my most highly cited publications. Interest in them has grown in recent years with the data sovereignty movement.

Tai Tokerau

The Tai Tokerau (Northland) region is my ancestral home and also my puna (wellspring) for inspiration and hope. With the encouragement of my Ngāpuhi tribal mentors, Jonathan Mane-Wheoki and Patu Hohepa, I researched and wrote the 2003 book Tai Tokerau Whakairo Rākau, cataloguing Northland Māori wood carvings in public collections around the world and writing about the practice of this art form. Several carvings were parts of pātaka (Māori raised store houses), dating from the 19th century and earlier. The plight of disassembled Māori buildings and other taonga Māori that have been accessioned into museums and acquired by private collectors, often with little or no information about their community origins, concerns me as it does many others.

Reclaiming tribal stories for northern taonga and building parts dispersed across collections around the world brings them and their histories back into our kōrero (narratives). Completing the fractured story of the rangatira Titore’s gifts of taonga to King William IV in 1834 and 1837 and rediscovering Thomas Kendall’s 1823 consignment of whakaro rākau (including incredible pātaka carvings) sent to the Church Missionary Society in London, have been some of my most satisfying work. The 2014 repatriation of the silver medal that belonged to my ancestor Te Pahi, whose death in an 1810 massacre by European sailors split his community, demonstrated to me how a taonga can reunite communities, even after 200 years apart. Architecture is usually considered a generative activity based on the assembly of parts to create new space. Architectural disassembly and parts dispersal are particular threats for Indigenous buildings, which requires action and attention.

Māori Architecture and Beyond

My return to Auckland to teach at the School of Architecture and Planning in 2003 coincided with writing a run of books, chapters and articles on customary and contemporary Māori art and architecture. The 2009 book Māori Architecture was an opportunity to publish a history that started with Polynesian arrival and ended in the present day. It is humbling to see its influence on the practice, promotion, teaching and understanding of Māori architecture, here and abroad. Even more ambitious projects have followed. Art in Oceania was a Pacific art and architectural history written in collaboration with six other writers and it won the 2014 Art Book Prize (formerly the Banister Fletcher Prize) for the best art or architecture book published in English anywhere in the world. The prize money was used to buy copies of the book for libraries around the Pacific. Toi te Mana, the Māori art and architectural history written with Ngarino Ellis and started with Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, is a 12-year, soon-to-be-published project. I regard books and articles as emissaries that take on their own lives once they are in circulation and extend ideas well beyond my own sphere of influence.

My early research into the whakapapa of Māori architecture argued that architectural movements are perpetuated through teaching, not building, as demonstrated by the enduring legacies of Ngata’s School of Māori Arts and Crafts and Te Puea’s Tūrangawaewae Carving School. This is as true today as it is in history.

I have been privileged to be part of the teaching staff of the University of Auckland School of Architecture and Planning, which is now called Te Pare in memory of my late colleague Rewi Thompson, and to lead it during one of its most difficult times, the Covid pandemic. I have had the pleasure of teaching hundreds of talented students and seeing them flourish in practice and in other professions. Some of my former students are now my colleagues: Dr Karamia Müller, Dr Charmaine ‘Ilaiū Talei and Lama Tone. They are part of their own Pacific architectural movement and are actively researching, publishing, teaching, curating and designing for their communities. Together and with others we are influencing practice and – by extension – the built world by boundary pushing, normalising Indigenous approaches to architectural design and ensuring that architecture enhances the life and cultures of Māori and Pacific people. A contribution to architecture is one that positively influences lives of others through whatever means you have available, whether they be words, discoveries, teaching or design.

Top image: 'Ahakoa he Iti’ by Keri Whaitiri and Rachael Rakena in Lightscape exhibition, curated by Deidre Brown, at Cathedral Square, Ōtautahi Christchurch, 2004. Photograph by Art and Industry.