Peter Richardson traces the story of government architecture in New Zealand from the mid-19th colonial era to the brink of 20th-century modernism.

It’s around 10 o’clock in the morning. A fox terrier scampers through the architectural drafting office, followed by its owner, New Zealand’s first Government Architect, John Campbell (1857–1942). Without glancing at his staff, Campbell walks through the office, deliberately ignoring any inactivity or tobacco smoke. Repeating this routine every working day, Campbell is compelled to discipline only one draughtsman for smoking in this smoke-free workplace: Arthur Ford, who, being deaf, does not hear the advance patter of the fox terrier that forewarns other staff of Campbell’s arrival.

It’s around 10 o’clock in the morning. A fox terrier scampers through the architectural drafting office, followed by its owner, New Zealand’s first Government Architect, John Campbell (1857–1942). Without glancing at his staff, Campbell walks through the office, deliberately ignoring any inactivity or tobacco smoke. Repeating this routine every working day, Campbell is compelled to discipline only one draughtsman for smoking in this smoke-free workplace: Arthur Ford, who, being deaf, does not hear the advance patter of the fox terrier that forewarns other staff of Campbell’s arrival.

With the dog curled up under Campbell’s desk, order has been asserted in the office. Campbell will leave at 1pm, return at 3pm and finish at 5pm, preceded by his fox terrier. He will receive his instructions from the Minister of Public Works, and manage a dozen staff to deliver the Minister’s work programme. Everyone in the office is focused on a very particular set of building types: post offices, customs houses, prisons, police stations, courthouses, departmental offices and the Parliament Buildings.

This account of Campbell’s office, circa 1917, is drawn mainly from the recollections of one of his staff, Walter Vine. Campbell’s working hours and routine suggest a high degree of trust and mutual respect. (Sporting a slightly smokestained moustache, Campbell could hardly be too heavy-handed in enforcing the Government’s no-smoking policy.) A closer look at the office reveals it comprises a remarkably homogenous team; a high proportion of senior staff are, like Campbell, born and trained in Scotland.

How had such an office become established in New Zealand? Throughout the British Empire, the ultimate inspiration for government architect's offices was HM Office of Works; in New Zealand, the more immediate model was the Colonial Architect’s offices in the Australian colonies. Even so, New Zealand did not immediately recognise the need for such an office, and had no overall plan for its development.

En route from Sydney in 1840, New Zealand’s first Governor, William Hobson, had selected an architect from the New South Wales Colonial Architect’s office, William Mason (1810–97), to be New Zealand’s Superintendent of Public Works. Mason believed Hobson had promised he would be promoted to Colonial Architect once he proved his abilities in New Zealand. He raised the matter some months after taking up his new role, but Hobson asserted he had not intended to create the office of Colonial Architect.

With little prospect of architectural work, Mason resigned in 1841. It was not until the late 1860s that a Colonial Architect’s office was established. The impetus was Treasurer Julius Vogel’s commitment to the growth of central government and his ambitious programme of immigration and public works, intended to stimulate the then stagnant economy. To design the government buildings Vogel’s policies required, his son-in-law William Clayton (1823–77) was appointed Colonial Architect in 1869.

Born in Tasmania, Clayton had trained as an architect in England, probably under Edward Lapidge (1779–1860). His major governmental work in New Zealand was the Classical Italianate timber Government Buildings in Wellington (1875–76). Working with a standard set of architectural forms, virtually a ‘kit of parts’, he erected other Classical Italianate buildings, and some Gothic works, throughout the colony, creating a recognisably official image for the Government. The Napier Courthouse (1874-75) and Chief Post Office in Christchurch (1877–79) are examples of this work.

In 1877 Clayton died while he was serving as Colonial Architect, and his office went into decline. He was not replaced and his former staff (Pierre Burrows and later Charles Beatson) served in lesser roles, becoming responsible for works in the North Island only.

John Campbell’s career was on a very different trajectory. In 1883, shortly after arriving in New Zealand, he took up a position in the Dunedin office of the Public Works Department as an architectural draughtsman. In 1888, he was transferred to Wellington, where, in 1889, he became draughtsman for a newly created Public Buildings Department. That department merged with the Public Works Department in 1890, and Campbell's title became ‘Architect’ in 1899. He remained in charge of the design of government buildings in New Zealand until his retirement in 1922, holding the title of Government Architect from 1909.

For much of his career, Campbell worked for the Liberal Government (1891–1912), designing the buildings needed to support an administration committed to wide-ranging social and economic reforms. His early works were predominantly in the Queen Anne style, which was associated with progressive causes such as housing for the poor, free public education and votes for women. Increasingly, and especially in the 20th century, his works were Edwardian Baroque, a style architects promoted as distinctly British and reflective of New Zealand’s strong imperial bonds.

There are distinctive and sometimes obvious British models for major works: the administration block of the Dunedin Gaol (1895–97) recalls the northern block of London’s New Scotland Yard (1887–90), and the Auckland and Wellington Post Offices (both 1909–12) are modelled on London’s General Post Office (1907–10). The Hokitika Government Buildings (completed 1913) recall the London headquarters of the Post Office Savings Bank (1899–1903).

The high point of Campbell’s career was the Edwardian Baroque Parliament House, Wellington (1912–22), the most ambitious architectural project attempted in New Zealand at that time. It was never completed, and Campbell retired in 1922 following construction of the one wing that was built. In 1923 the Public Works Department appointed John T Mair (1876–1959) as Government Architect. His office flourished under the first Labour Government (1935–49), elected on a platform of social and economic security. Before becoming Government Architect, Mair was architect to the Education Department, and he had earlier been the Defence Department’s Inspector of Military Hospitals. He had trained under William Sharp (Invercargill Borough architect, surveyor and engineer), studied at the Beaux Arts-influenced Pennsylvania School of Architecture, and run his own architectural practice.

Mair did not share the reforming zeal of his principal Minister under the Labour administration, Hon. Robert Semple. Semple demonstrated his flair for publicity and delight in modern technology when he mounted a Caterpillar tractor to drive over an old wheelbarrow and shovel. By contrast, Mair was not willing to drive over architectural tradition to adopt ‘radical’ European Modernism. His buildings instead create a gentler image; the architectural expression, perhaps, of the avuncular smile captured in the photograph of Labour Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage which graced many New Zealanders’ homes.

Mair’s works as Government Architect are in the populist and historically inspired styles of the 1920s and 30s: Stripped Classicism, and Zigzag and Streamline Moderne, now known as Art Deco. His office is perhaps best known for the Stout Street Departmental Building, Wellington (1938–40), a Streamline Moderne design with a Stripped Classical entrance porch. Mair also developed more up-to-date designs for secondary works, such as the Classical-style Blenheim Court House (1937–38) and the Art Deco Palmerston North Police Station (1938). Reflecting 1930s nationalist thinking, his later designs incorporate Māori decorative elements. The Stout Street Departmental Building, for example, incorporates koru as decoration on the façades of the entrance porch.

Mair found himself operating in a very different public service from Campbell’s. A decade before his appointment, the Government passed the Public Service Act 1912, establishing a unified structure in place of the quasi-independent public sector fiefdoms in which Campbell’s office flourished. This Act was important in codifying public service career paths but was not drafted with architects in mind. Reporting to the Public Works Department’s Under-Secretary, Mair could at times become frustrated by his office’s lack of autonomy, and the dominance of the department’s engineers.

To judge by the popular press and political rhetoric, the Government Architect’s office was regarded much like the wider public service: generally competent but lacking the flair and innovation to be found in the private sector. More balanced assessments might have acknowledged its importance to nation-building and the high quality of its major projects, as well as the challenges given the available budgets. Nowhere was this better illustrated than in Wellington’s Parliamentary precinct, where successive attempts to create an impressive architecturally coherent ensemble failed, leaving behind fragments of unrealised proposals. In 1940, this precinct comprised one wing of the Edwardian Baroque Parliament House, a Gothic Parliamentary Library, the timber Italianate Government Offices, and a timber Italianate Government House that was destined for demolition.

The lack of architectural coherence does not reflect the quality of the individual components; it is a consequence of the hard realities of changing political priorities, tight budgets and faltering political will. Whatever the final assessment of its works, the office had rightfully secured its place in the civil service and the wider architectural profession. The days of gentleman’s office hours, when the patter of a fox terrier would warn staff of the impending arrival of the Government Architect, had long since passed. By 1940, the office was well integrated into a modern public service and was set to play an increasingly important role in serving the New Zealand public.

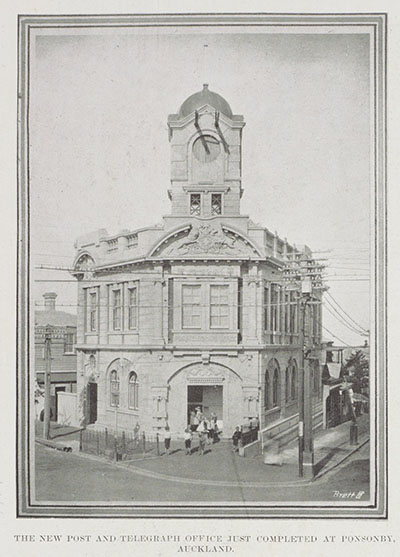

Heritage image: Ponsonby Post Office, taken from the New Zealand Graphic, 12 February 1913, p20. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19130212-20-1.