Riding the waves

What is the ‘right way to live’? Architectural commentator and educator Bill McKay takes a circumspect look at the transformation of New Zealand.

The title of New Zealand’s Biennale pavilion, ‘Last, Loneliest, Loveliest’, can be seen as an ironic and provocative one. Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘The Song of the Cities’ serenaded Auckland as a far-flung outpost of the British empire, remote but lovely, a jewel of a harbour city in the South Seas. That romantic perception of New Zealand continues to be encouraged through tourism advertising and the supporting role played by New Zealand’s photogenic landscape in Hollywood blockbusters such as The Lord of the Rings and Avatar. To visitors, our cities are mere staging posts for voyages into our (allegedly) clean and green countryside and the spectacular mountains beyond.

Our cities, however, are where most of us live, and to a large extent, ever since their inception, they have been pale reflections of the places we came from. In one of the last lands to be settled in human history, we are still trying to find the right way to live. As long ago as 1943 the New Zealand poet Allen Curnow wrote, “Not I, some child, born in a marvellous year, / Will learn the trick of standing upright here”,[1] and it often seems we haven’t quite learned it yet. For much of the past century New Zealand fretted about the evolution and expression of a sense of identity, and the associated issue of its relationship with Britain, the ‘Mother’ from which it has gradually separated. Today, the discussion about identity has more poles, as a more diverse crew populates our metaphorical canoe: the indigenous Maori, the descendants of European colonists, migrants from the Pacific Islands and, most recently, arrivals from all over the world, especially Asia. New Zealand remains in flux, a coastal nation exposed to wave after wave of people, ideas and influences.

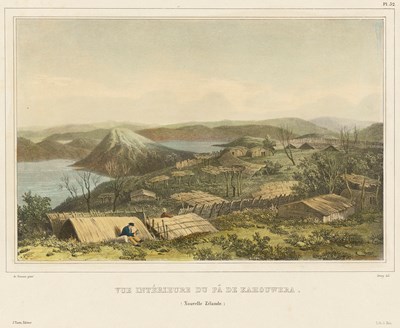

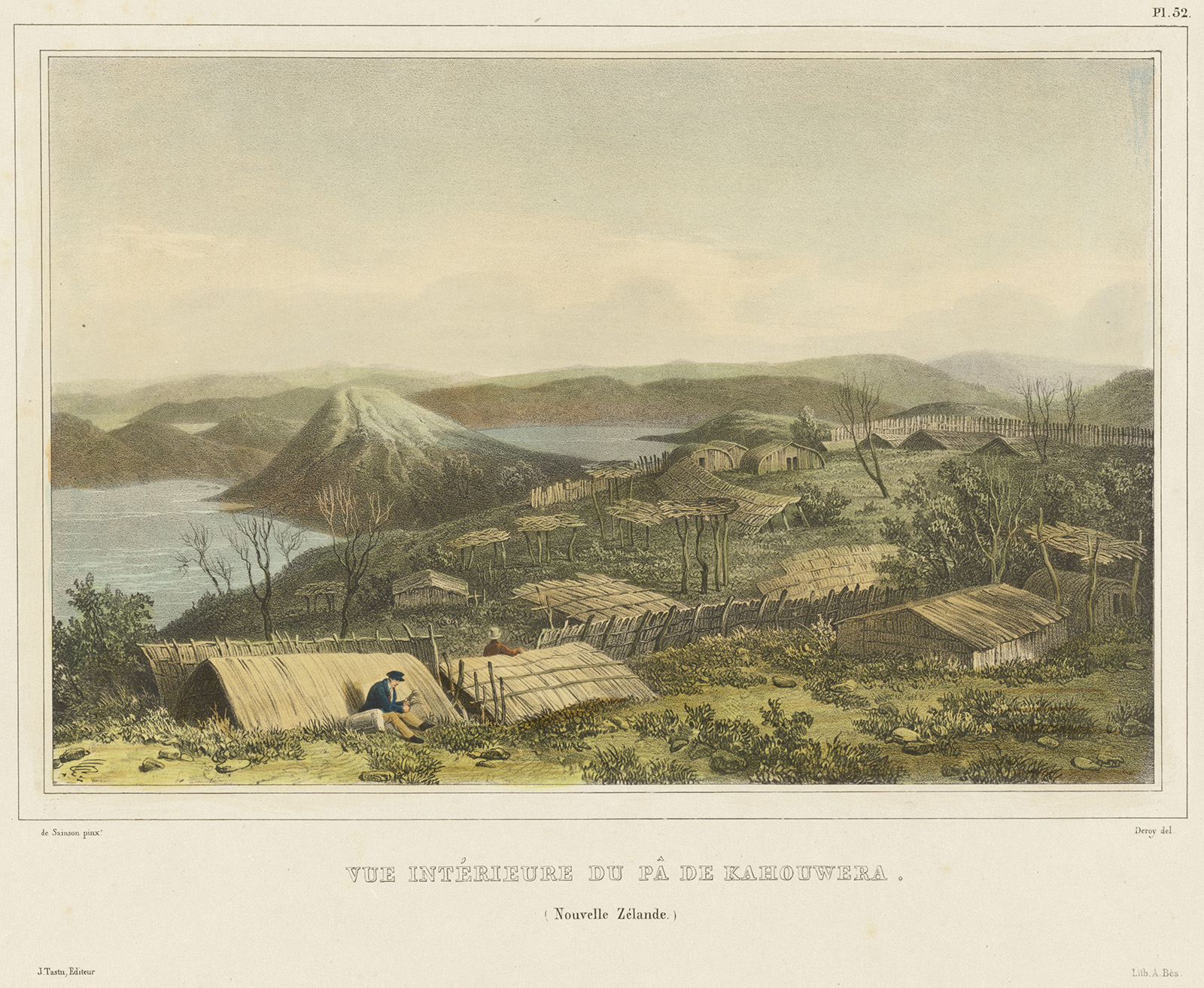

All leave their mark. Aotearoa New Zealand is a land of settlers who have gone about transforming the landscape to suit their needs. Maori – and even they have been here for less than a millennium – descend from island-dwelling Oceanic voyagers who had to adjust to a colder climate with different flora and fauna. In a land where most of the foods they brought with them wouldn’t grow, a place with winters, and carpeted with forests quite different from elsewhere in Polynesia, Maori had to deploy new architectural materials and forms. When British colonisation got under way in the early nineteenth century, many building materials and architectural types were imported. But the process of settlement was not so much a case, as many think, of adapting the buildings to the New Zealand landscape and climate. Rather, it was the landscape that was highly modified, transformed and terra-formed to suit the settler culture, with forests replaced with grass and roads and railways driven through hills. The existing natural environment was overlaid with an alien one and, as many native species of flora and fauna died out, New Zealand became, and remains, the extinction capital of the world. Maori were earthmovers, too, abandoning the perched-up buildings and open, pavilion-like fale of their Pacific homelands to dig into the ground, creating whare (houses) that were half-buried, and massive pa (fortified settlements) that terraced hillsides.

All of the people who have come to New Zealand, down through the years, have brought an enormous amount of social and cultural baggage. It’s not surprising, perhaps, that the country’s settlements often resembled temporary encampments. (Pip Cheshire, one of New Zealand’s leading architects, has said that, in a sense, we’re still on the beach, “pulling the packing cases up above the high tide mark”.)[2] It is entirely appropriate, then, that New Zealand’s pavilion in Venice literally takes the form of a pavilion – a sail, a tent in suspension, a cloud, a wisp of smoke, a conversation of words and images.

The just-built, the being-built, the might-be-built, the never-to-be built – these conditions are all familiar to us as New Zealanders, and all are thrown into relief by the Venetian building housing our exhibition, a building with a history only two centuries briefer than the history of the human habitation of New Zealand.

Rem Koolhaas’ title for the Biennale Architettura 2014 is ‘Fundamentals’. So, let’s get down to basics: our land, comprised of several islands, is geologically young; it has a history of earthquakes that don’t just shatter cities such as Napier [1931] and more recently Christchurch [2011], but shift shorelines, such as those in Wellington, the country’s capital. In our shaky isles, where hills slip into valleys and tides gnaw at the coastline, the major cities are built on seismic fault-lines and river plains, and in volcanic fields.

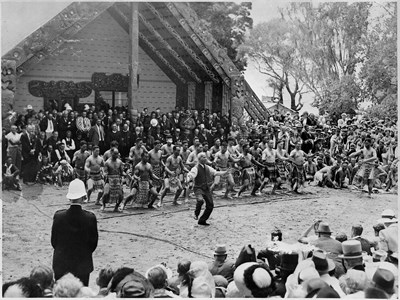

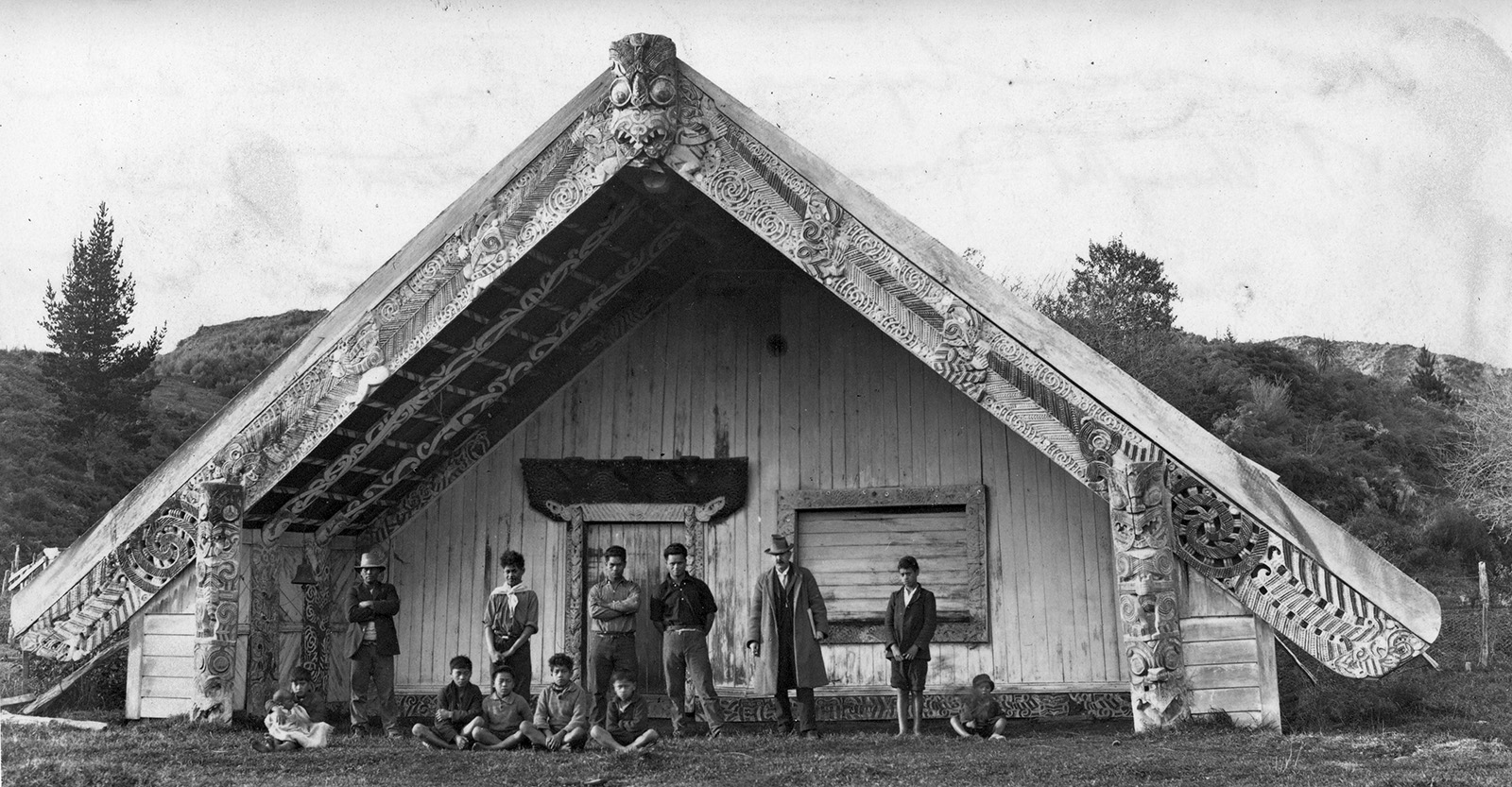

‘Fundamentals’, in a place where the earth cannot be relied upon, means rather more than windows, walls and floors. Beyond the staple concerns of any national architecture, issues such as climate and landscape, materials and the inspirational potential and physical survival of vernacular buildings, the interaction between our different tribes of people has been crucial in the development of ways of living here, as has the continual inflow of overseas ideas and influences, modernism being just one. The wharenui or meeting house of the Maori is an iconic New Zealand structure, yet it is not an ancient one. Dating from the 1860s, it is an evolution of older forms, but also an architectural expression of the meeting of two cultures, Maori and European. The wharenui was a response to the European church but also an architectural means of accommodating new needs in an era of change, conflict and warfare. Our land is not new not just in the sense that it was discovered relatively recently; like the sea, our land and our society are new every day.

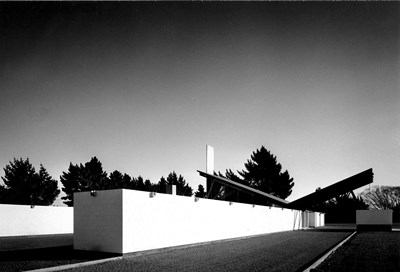

The theme that national pavilions in this year’s Biennale have been asked to address is ‘Absorbing Modernity: 1914–2014’. In New Zealand, there has not been, to use Rem Koolhaas’ phrase, an “erasure of national characteristics” because these characteristics had never fully developed. And modernism, rather than eroding a national or vernacular architecture, was just another of the colonising forces and influences that have rolled through the land. However, modernism after the Second World War did allow young architects to throw off the conservative mantle of a muddled Edwardian historicism and develop a regional variant of a contemporary international style. Indeed, modernism in New Zealand was the architectural vehicle in which New Zealand travelled in the journey towards a national identity.

However, the liberating effect of modernism was common throughout the world, and as it reached comfortable old age did it have a stultifying effect on the development of new architectural ideas? Has it had a homogenising effect on building around the world? Of course it did, and of course it has. And to what extent can the more successful late-twentieth-century output of architects in New Zealand be considered just a regional variant of modernism? Well, to a large extent. But what has been emerging in New Zealand over the last century is a greater engagement with the cultures of the peoples of the Pacific region and Asia. This promises to produce an architecture not of national identity, but of place and people.

David Mitchell, the Creative Director of New Zealand’s pavilion, is in many ways typical of the species ‘New Zealand architect’. He is a traveller, physically and intellectually. He has practiced in a series of partnerships, most notably with Jack Manning and, for many years, with his work and life partner, Julie Stout, who is also part of the New Zealand pavilion creative team. Mitchell has combined practice and teaching; less typically, he has written on architecture, most notably in The Elegant Shed: New Zealand Architecture since 1945 [with Gillian Chaplin, Oxford University Press, 1984], which was also the basis of a television series. He has sailed around the Pacific and has practised in Hong Kong (while living on his yacht). Lest he start to resemble that familiar Pacific trope, the beachcomber, it should be pointed out that he returned from his Pacific sojourn to concern himself with architecture in New Zealand. Many young New Zealand architects take the itinerant route, travelling abroad to work in Europe or the Americas and then returning home. But this Biennale, Koolhaas has specified, is about architecture, not architects.

Architecture in New Zealand has often been expressed in a contradictory manner, as befits a new society in an unfamiliar world, a place in which the urgency of meeting immediate needs tends to outweigh the desirability of planning for the future. From the start of settlement, ambition was heavily tempered by pragmatism. Consequently, our architecture may seem strangely ordinary to the rest of the world: a stalky architecture of timber and tin, more sticks than stone, transient houses of cards. But, as Mike Austin and others have argued, this architecture should not be seen as lacking the traditional virtues of Western architecture: firmness and commodity (delight being always harder to achieve, anywhere).

This architecture is not a halfway-house between settlement and civilisation. It is something else, something increasingly pervaded by the spirit of our hemisphere, in our watery quadrant of the world.

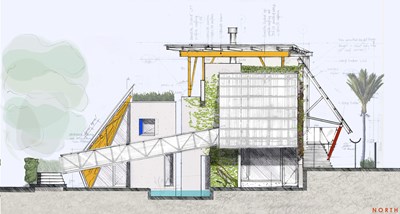

Architecture responsive to the Oceanic condition is not so much temporary and transient as light and malleable, flexible and responsive. In this, it has a commonality with the woven architecture of Maori whare, knitted from harakeke (New Zealand flax), more like baskets than buildings, and Maori meeting houses, dynamic tectonic structures of posts and poles and post-tensioning. Like the fale of the Pacific, whose thatched roofs are simply renewed when cyclones blow them away, our timber structures shimmy and sway in earthquakes, when brick or block would crack and collapse.

The most prominent locus for the emergence of this neo-Pacific architecture is Auckland. Of our largest cities, Dunedin was the ‘Edinburgh of the South’, and Christchurch ‘more English than England’ (until many of its settlement-era buildings came crashing down). But Auckland is almost another island; it is the largest city in Polynesia and home to the largest population of Pacific Islanders in the world. Peter Wood is one of the architectural writers to have adapted from biology the argument that in comparison with its parents, any hybrid is strange as it assumes new proportions and characteristics.[3] Wood suggests that a bicultural architecture follows this trajectory of appreciation; by its nature it is initially considered odd, and even perceived as ugly. Modernism arrived in New Zealand during a period in which government policy was to assimilate and integrate Maori people into the dominant Pakeha culture. A person of mixed racial heritage could be called ‘half-caste’, that is, someone trapped between two worlds. Now, 50 years later, when biculturalism is official government policy, a person of mixed heritage is regarded as being at home in both worlds.

Auckland is an awkward isthmus at the narrowest neck of the country, on a site nearly encircled by seas and spotted with the dormant cones of past volcanic eruptions. It is New Zealand’s gate city, a sea and air port where most immigrants settle. Fewer than half of all Aucklanders were born in the city, and scores of languages are now spoken there. Architecturally, Auckland is still fairly ordinary, but in recent decades there has been an acceleration in the city’s growth and with that an improvement in its architecture, including the emergence of buildings that seem more natural here than the imports of the last 150 years.

The recent house that David Mitchell and Julie Stout have designed and built for themselves in an Auckland maritime suburb is a collage of leaning slabs of concrete and angled sheets of plastic. It has been duly derided as the “ugliest house on the North Shore”, which is saying something, in a city with burgeoning developments of McMansions and tract housing. It’s a long way from the romance of “last, loneliest and loveliest”. Perhaps a new architecture is emerging, a hybrid, as new breeds tend to be, of ideas and influences that have gone before. Modernism – modernity – has been just one of the waves that have washed over these shores. We live in the Pacific. We have to be good at riding the waves.

Bill McKay teaches at Masters level and runs the MArch (Prof) Professional Studies courses in the School of Architecture and Planning.

Footnotes

1 Allen Curnow, The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, Sailing or Drowning [Wellington, Progressive Publishing Society, 1943].

2 ‘Pip Cheshire, Unresolved Romantic’, Urbis Design Annual 2003, 34–41.

3 Peter Wood, Reflections on Culture and Change in New Zealand Architecture: Life in the Dog Box (or, Te Papa: ‘Our Place’ is a Dog), 2004 Pacific Colloquium, Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington.

This essay was first published in the catalogue for ‘Last, Loneliest, Loveliest’ – New Zealand's inaugural exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale.