Charles Walker reflects on the design philosophy and works of Patrick Clifford and Architectus.

Staying true to type

In an introduction to a 2004 book on the work of Architectus [Architectus: Bowes, Clifford, Thomson; New Zealand Architectural Publications Trust], Tony van Raat identified the practice’s “critical and rigorous approach to the problem of making architecture”. Van termed this approach ‘ideological’ because it evidenced a concern for establishing an intellectual basis for practice – an understanding of the ‘why’ and not just the ‘how’ of architecture – that is still rare in New Zealand.

At that time, too, Architectus had just joined a consortium of Australasian practices and was seen as a firm on the cusp of bigger things. Yet, in the style-fixated New Zealand scene of the late 1990s and early 2000s, critics saw Architectus’ attachment to rigorous planning, tectonics and craft as a bit, well, old-fashioned.

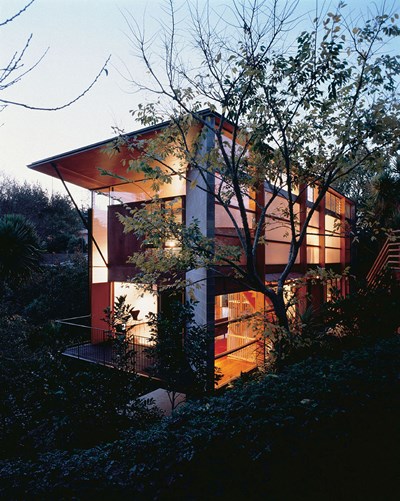

A decade on, Architectus is in the vanguard of a newly mature and confident New Zealand architecture. Perhaps more significantly, the ambitious theme chosen for the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale by its Director, Rem Koolhaas – ‘Fundamentals/Absorbing Modernity’ – provocatively re-frames relationships between universal abstraction and local practice, and signals a renewed interest in questions that Architectus has been asking for close to 30 years. Patrick Clifford’s own lantern-like pavilion from 1995 (the Clifford-Forsyth House; see gallery below), which is included in New Zealand’s Biennale pavilion, seems to have anticipated Koolhaas’ theme.

Clifford suggests that Koolhaas’ focus on building elements and the socio-historical foundations of practice presages a desire on the part of architects to re-engage with big ideas about context, meaning and the continuing relevance of the profession in increasingly fluid and complex societies. That such issues have been neglected is perhaps partly due to the context in which today’s senior architects were trained. Clifford says that he and his partners in Architectus, Malcolm Bowes and Michael Thomson, were educated in “an era without precedent”. By this he means that the idea of studying architecture by looking at what other architects had done, or seeing one’s practice as part of a tradition, was discouraged in favour of an approach in which designing was a matter of “personal expression”.

“It took me a while after I left architecture school to realise I could actually study architecture – by reading books, and looking at buildings, their history and how they were made,” Clifford says.

Ironically, even though students are now exposed to more examples of architecture than ever before, he remains skeptical about the real value of the unfiltered torrent of styles continually being uploaded by design blogs.

Clifford’s declared interest in precedent invites a discussion of typology, another unfashionable idea now being rediscovered in architecture schools and offices around the world. The architect and theorist Rafael Moneo has noted that architecture is not only described by types, but is produced through them. The notion of type offers a methodology for linking past and future, as well as a means of thinking through the relationship between a building and its environment. Clifford sees typology as a kind of architectonic knowledge transfer or ‘operative theory’ that is simultaneously universal and local. Generic enough to accommodate international trends and differences, typology is specific enough to anchor practice to local cultural, social and political circumstances.