Oceanic architecture

From the whare to modernism, Dr Mike Austin explores the history, ideas and forms of Pacific architecture.

The Pacific Ocean accounts for one third of the surface area of the Earth. It is vast and seemingly empty, although of course it has inhabitants, many of whom view the Pacific as ‘a sea of islands’. The last Pacific islands to be settled were rediscovered in 1769 by the English navigator, James Cook. These islands, named ‘New Zealand’, were inhabited by Maori who had themselves settled in the land they called ‘Aotearoa’ several centuries previously, having sailed from the centre of the Pacific, which their ancestors had populated over several millennia, by island-hopping from the Far East. The early European explorers appreciated the skills and craft that achieved these journeys and they also admired the architecture they encountered. Cook had on board his ship a Polynesian from Ra’iatea in the Society Islands, Tupaia, who was able to communicate with Maori. As Tupaia’s drawing [see gallery] of a Maori presenting a crayfish to a British naval officer indicates, Europeans initially relied on Maori for food and shelter. The settlers soon forgot about this early vulnerability and set about establishing their own way of life and architecture on this far-flung frontier of the British empire. When, in the 1890s, Rudyard Kipling described Auckland as “last, loneliest, loveliest, exquisite, apart”,[1] he was not, we assume, referring to the settlement’s colonial architecture, but rather to its volcanic and watery landscape.

In 1900, the Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects published a review of New Zealand architecture in which local architect Samuel Hurst Seager spoke of “ambitious attempts to reproduce the architecture of the Old World resulting in shams and deceits”[2] and suggested that Maori buildings “though excellent examples of savage art, are scarcely suitable as standards on which to found our national taste”.[3] In 1940, the Head of the University of Auckland School of Architecture proposed that Maori architecture “apart from some influence in detailed ornament could have little effect upon contemporary design”.[4] This opinion contrasts with that expressed 100 years earlier by the British naturalist and painter George French Angas, who had toured New Zealand recording what he called “the singular and beautiful architectural remains of these [Maori] people”.[5]

A storehouse in a storehouse

The Auckland War Memorial Museum was built to commemorate the 18,000 New Zealanders killed in the First World War. This neoclassical building, with its Doric columns and Portland stone façades, was completed in 1929, the year in which Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion was realised, and six years after Le Corbusier’s Vers une Architecture was published. The Auckland Museum housed Maori artefacts, a wharenui (meeting house), pataka (storehouse) and waka (canoes). As Nicholas Thomas[6] has pointed out, remarkably such collections have survived the changes in architectural and curatorial fashions to emerge as the stable foundations of the museums that store them. In the New Zealand Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale we have reversed the original act of cultural cannibalism by commissioning a carved whata-a-rangi, “a small pataka elevated on one tall post,”[7] in which to display a model of the museum.

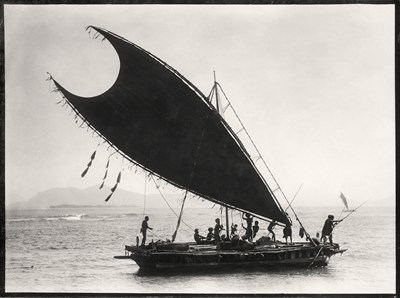

The Pacific house is often dismissed as unnecessary – merely a grass hut in a Garden of Eden. This is not, however, the primitive hut that commentators from Vitruvius to Rykwert[8] have claimed to be the origin of all architecture. Instead, it is derived from – and many examples resemble – an inverted canoe. Several implications follow from this genesis, such as the use of tension as a construction principle, and the building of the house from the roof down, rather than on top of supporting walls. The Oceanic connection between house and boat is acknowledged in numerous myths and stories.

Pacific pavilions

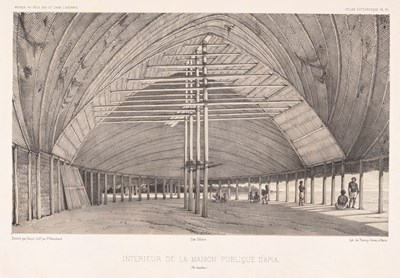

The Oceanic way of building boats involves duplicating hulls: “One would imagine that a contrivance so simple and practical for procuring stability and increased carrying capacity would have been adopted everywhere, but as a matter of fact it belongs almost exclusively to the Indo-Pacific area.”[9] Until very recently no one would have thought that the America’s Cup, the premier global yachting contest, would be sailed in multi-hulled craft originating from the Pacific. In the same way that we can characterise the Oceanic canoe as uniquely multi-hulled there are a number of generalisations that can be made about Pacific Island buildings. The first is that they are universally single-celled pavilions. Small or large, Pacific buildings are always unicellular, and free-standing in open space. Differentiation and separation are achieved not by walls and partitions, but by space, much as islands are separated by sea. This term for this spacing is va, an Oceanic word, that, with numerous complex variations and translations, is applied to both the social and physical worlds.

Fundamentals

In the Pacific the gabled house form, which goes under variants of the term fale and which is known in New Zealand as the whare, is also standard. The gable cross section is, surprisingly, an inherently unstable form and it is, of course, a form that is not confined to the Pacific. The characteristic of the gable in Oceania is that posts support the ridge pole, which has the structural benefit of eliminating outward thrust on the wall posts; in the West this lateral load is usually resisted by trusses or buttresses. Sometimes this ridge post is truncated to become a king post, but always the ridge is propped.

These props have all manner of symbolic associations. In the Maori whare the ridge post, or poutokomanawa, is the heart of the named ancestor who is the house. This identification is detailed and literal. The gable house form, in all its variations, is utterly fundamental to Pacific architecture. The floor of the Pacific house, on the other hand, varies and is conceptually separate from the rest of the building. Sometimes it is a raised platform, sometimes it is dug into the ground for insulation. Walls are porous or even non-existent; often, if they are used, they are suspended from the roof.

The visitor to a Pacific settlement finds deserted and abandoned houses, because these buildings are replaced, rather than maintained and repaired in the manner of, to take an extreme example of renewal, the Ise Grand Shrine in Honshu, Japan, which is ritually rebuilt by each generation.

Oceanic houses all have a life, and therefore a death. On islands, as Arata Isozaki has claimed, Thanatos is always near.[10] The apparent structural simplicity of the Maori whare is deceptive. It looks like post and beam construction, but it is tectonically different to European building techniques. The system relies on tension cords which are slung across the building, pre-stressing and locking the frame and tying the building to the ground.[11] As with the canoe, the Pacific building strives to achieve stability through lightness and tension; the Western way generally has been to add weight, even nautically, where heft is applied as keels and ballast.

The meeting house

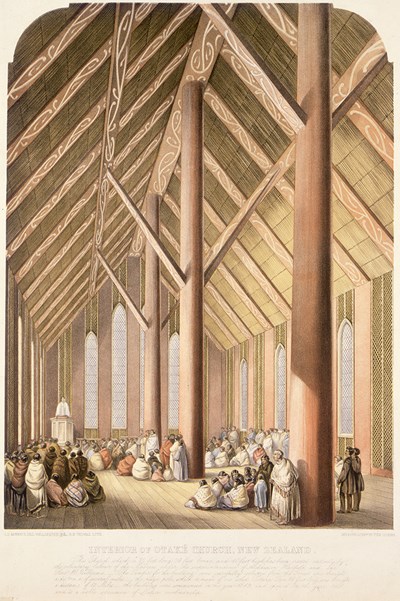

Since European contact Maori have continued to follow their own construction trajectory, responding to the imported architecture of the Christian church by building meeting houses based on churches. Church and whare, both large spaces for gatherings of people, share purpose and form, a congruence famously expressed in Rangiatea [Otaki, 1851], usually described as a Maori church.[12] The canonical form of the meeting house was established by Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki, who renovated Te Tokanganui-a-noho in 1885. This single space building, with one door and one window opening onto a sheltering porch and a backbone ridge supported on ridge posts, was the model for what has become the traditional form for the meeting house.

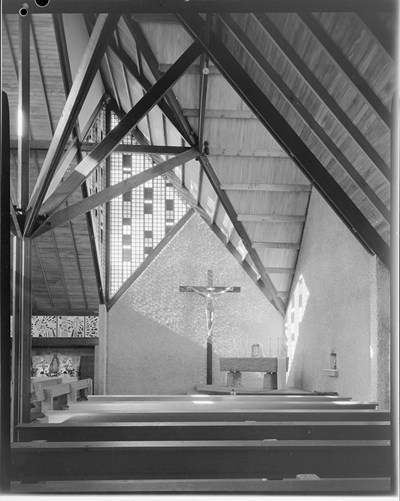

More than a century after the building of Rangiatea, the Chapel of Futuna in Wellington was commissioned to commemorate a Catholic martyr who died on the eponymous Polynesian island. The chapel’s architect, John Scott [1924–1992], who was of both Maori and Scottish descent, interrogated the meeting house form, splitting it and opening it up. However, he kept the poutokomanawa, the heart post. Scott also designed a building commemorating the Maori Battalion, the celebrated New Zealand army unit which fought in North Africa and Europe in the Second World War. This is a building with tattooed carved timber panels on the façade, very aware of its Brutalist origins.

Modernism

The beginnings of the modern were provoked, according to Bernard Smith, by fascination with the ‘other’ of the Pacific world.[13] The early modernists used Oceanic artefacts in order to overturn their own traditions; Loos’ Papuan paddle and Semper’s screen walls referred to the Pacific. Vogt has argued that the floating architecture of modernism, and specifically Le Corbusier’s pilotis, derive from the Pacific.[14] Today’s modernist revival, with its obsession with tension structures and joints, has some affinities with Oceanic architecture.

Modernism arrived in New Zealand after the Second World War. A generation of young men who survived service were variously disillusioned or energised by their experience. Some trained as architects, called themselves ‘The Group’ and constructed houses that went back to fundamentals.

They nodded at indigenous architecture, giving one of their designs – a dwelling with a sheltered gable porch – the ironic name ‘Pakeha House’. New Zealand architecture has followed this pragmatic tectonic approach ever since, using sticks of timber and sheltering roofs. Immigrant architects often see the potential of this tradition and reinterpret these themes.

Architects in New Zealand are endlessly scouring the local environment for architectural sources, but always with their gaze directed over the horizon. The hope for the future is for the production of an architecture resulting from the grinding together of land and people in the context of ever-present ocean. We keep searching for an Aotearoa New Zealand architecture, as a work in progress. As one visitor to New Zealand is reported, perhaps apocryphally, to have said, “It might be alright if they ever get it finished”.

Footnotes

- Rudyard Kipling, The Song of the Cities, first published in English Illustrated Magazine, May 1893

- S. Hurst Seager, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, 1900 (20 Sept) VII (19), 481–91, 482.

- Ibid., 490.

- Cyril Knight, 1840 and After (Auckland: Auckland University College, 1940), 180–81.

- George French Angas, Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand, Vol II (London: Smith Elder and Co, 1847), 88.

- Nicholas Thomas (ed), Rauru: Tene Waitere, Maori Carving, Colonial History (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2009).

- Elsdon Best, Maori Storehouses and Kindred Structures, Dominion Museum Bulletin no. 5 (Wellington, New Zealand: Government Printer, first published in 1916, reprinted 1974), 28.

- Joseph Rykwert, On Adam’s House in Paradise: The Idea of the Primitive Hut in Architectural History (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1981).

- Alfred C. Haddon, James Hornell, Canoes of Oceania (Honolulu, Hawaii: Bernice Puauahi Bishop Museum, 1936–38, 43.

- Arata Isozaki, The Island Nation Aesthetic (London: Academy Editions, 1996), 20.

- Mike Austin and Jeremy Treadwell, Constructing the Maori Whare, in Julia Gatley (ed), Cultural Crossroads: Proceedings of the 26th. International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand (University of Auckland:2009).

- Sarah Treadwell, Rangiatea Revisited (Gordon H. Brown Lecture, Victoria University of Wellington, 2008).

- Bernard Smith, European Vision and the South Pacific (Sydney: Harper and Row, 1985).

- Adolf Max Vogt, Le Corbusier, The Noble Savage: Toward an Archeology of Modernism (CambridgeMass: MIT Press, 2000).

This essay was first published in the catalogue for ‘Last, Loneliest, Loveliest’ – New Zealand's inaugural exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale.