Architecture and national identity

This article was first a talk about national identity – national peculiarity, if you like – as expressed in architecture. It was given in Wellington’s Futuna Chapel on 29 March 2009, and no better place to discuss the subject of national identity and architecture than the chapel, for it is a core component of New Zealand’s architectural identity. By John Walsh.

Certainly for architects Futuna Chapel is unique – peculiar, in a good way. When it was built it was something new in New Zealand architecture. It must have seemed shockingly contemporary when it opened in 1961, but it also made explicit reference to Maori and settler building traditions. It has been argued that Futuna Chapel is a fusion building designed by a crossover architect – or maybe a crossover building designed by a fusion architect. For John Scott was both Maori and Pakeha. New Zealand architecture needed a John Scott, and thank God we didn’t have to invent him.

National identity – that is, the desire to have one – has been a consistent New Zealand concern over the last century. Sometimes it has seemed that the one thing that makes New Zealanders different is our obsession with asserting that New Zealand is different. Peculiar, in a good way – even unique, like our native flora and fauna.

This trait has a long tail, winding back into the nineteenth century when a country that was still a colony took pride in democratic innovations like female suffrage. Later, when the first Labour government poured the foundations of one of the world’s first welfare states it seemed that egalitarianism would be set in concrete as a defining national characteristic. Another half century on, after New Zealand embraced market economics and globalisation with religious fervour, many of us basked in the international praise given for being such a neo-liberal trend-setter.

Now that prosperity and not equality is the incumbent political goal everywhere, it seems our distinction depends on our landscape. Our environment – clean and green as it is insisted to be – is our point of national difference. Chances are that when we choose a new flag we’ll pick something from nature to put on it. We’re meant to do that this year, in the centenary of the Gallipoli campaign when – we’re told – New Zealand “came of age” as a nation by sending young men to die for the British in their attack on the Turks.

I haven’t talked much about architecture yet, but I will get back to it. First, though, it might be worth noting that however sensitive we are about the issue of who we are, we’re not alone in fussing over the subject of national identity. Some bigger, older countries worry about this, too. The British, for example, have just put themselves through a referendum which asked the Scots to define themselves and made the English question their identity as well. And even the French, who gave us the term chauvinism, are constantly anxious about the dilution of their “Frenchness”.

So, what do our buildings tell us about ourselves? National identity came into architectural focus last year at the Venice Architecture Biennale. This is the world’s leading architecture event. It goes on for months, comprises scores of national exhibitions, and attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors. The Venice Biennale is many things: it’s partly an exposition of architectural practice; partly an investigation of architectural possibilities; and partly a critique of architecture’s current condition.

It’s also competitive. For a start, many countries run their own competitions to select an exhibition; then, in Venice, the national exhibitions compete against each other for media and public attention. The Venice Biennale is run by a bureaucracy – an Italian bureaucracy – that conducts its own foreign relations. It’s a bit like the Vatican, only with some women on staff. National exhibitions require the imprimatur of their governments, and most of the exhibitions are presented or supported by government culture departments or agencies.

Given the level of official involvement in the national exhibitions at the Biennale, it’s not surprising that countries are often self-conscious about what they present in Venice. It’s not so much a question of toeing the line, for at the Architecture Biennale the line is often difficult to discern. It’s more a case of putting your best foot forward. Measured against the competition, and viewed in the sublime context of Venice, exhibitors are under pressure to say something significant about their nation’s architecture. Even better would be to show that their nation’s architecture has some significance.

This pressure to stand out from the pack was more acute than usual at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. Normally, the Creative Director of the Biennale – traditionally a leading architect with a global reputation – sets a theme so broad and shapeless it can encompass any proposition advanced in any national exhibition. But in 2014 the Creative Director was the celebrated Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, a man with a strong ideological bent. Koolhaas was determined that his Biennale would be more focused and, it turned out, he had the necessary status and resources to make this happen.

The overall title Koolhaas gave to the 2014 Biennale was ‘Fundamentals’, a back-to-basics term indicating a concern with what is universal in architecture. That is, the constituent parts of buildings everywhere: façades and floors, walls and windows, ceilings and corridors, etcetera. But Koolhaas had another theme for the national exhibitions, and that was concerned with what is particular about buildings that are not anywhere, but somewhere. ‘Absorbing Modernity: 1914-2014’ was the subject the national exhibitions were asked to address.

Koolhaas explained what he meant: “In 1914, it made sense, perhaps, to talk about ‘Chinese’ architecture, ‘Swiss’ architecture, ‘Indian’ architecture… One hundred years later, under the influence of wars, revolutions, diverse political regimes, different states of development, architectural movements, and technological progress, architectures that were once specific and local have become seemingly interchangeable and global. Has national identity been sacrificed to modernity?”

The way Koolhaas described it, ‘Absorbing Modernity’ sounded like global architecture’s lost and found department. Koolhaas invited the creators of national exhibitions to consider what, in their architecture, has gone missing over the past century and what is still in place. That is, to measure the “erasure of national characteristics” against the “survival of unique national features and mentalities”.

Koolhaas’ theme was more complicated than it sounded, for ‘modernity’ is a surprisingly slippery term. Is it synonymous with modernism, the dominant architectural and cultural movement for much of the twentieth century? Or is it another word for modernisation, which all countries have embraced, out of choice or necessity, at some time over the past hundred years? Or is it just another way of saying ‘modern times’?

Many of the creators of the national exhibitions at the Biennale took Koolhaas’ theme as a prompt to look at the relationship, in their own countries, between local traditions – cultural as well as architectural – and modernism, which became the global architectural language of the twentieth century. Going down this track meant navigating some tricky terrain: Is modernism (or modernity or modernisation) compatible or incompatible with national styles of or approaches to architecture? How was modernism – a European phenomenon – realised around the world? Did modernism and does modernity mean homogeneity? In an era of globalisation is the “where” of architecture increasingly irrelevant?

So many questions. It’s hardly surprising that for the creator of each national exhibition the issue boiled down to: What’s so special about our country’s architecture and our country’s architectural story over the past century? Are we different? Does our architecture have its own identity?

For exhibition creators, these questions had practical as well as conceptual implications: what do you show in an exhibition and how do you show it? Koolhaas had set a hundred-year time frame, and in any country a lot of building happens in a century. The basic curatorial choice was between saying a little about a lot or a lot about a little. That is, go broad and present a survey of a hundred years’ worth of architecture, or go deep and focus on a moment within that sweep of time.

So, how were all these questions answered? There were 66 national exhibitions at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, and I want to discuss some of the ones that interested me, starting, of course, with the New Zealand exhibition.

The New Zealand Institute of Architects ran a competition for the position of Creative Director of the New Zealand exhibition at the 2014 Biennale. It attracted 26 entries. Many had a landscape focus – predictable, given our aforementioned identification with the natural environment, but not particularly helpful at an architecture Biennale.

Some dealt with the traditional vernacular settler tradition and its legacy – that is, sheds, and their successors. Some dealt with issues arising from the Christchurch earthquakes – the biggest things to (literally) hit New Zealand architecture in decades. When it came to developing an exhibition concept, most competition entrants took a survey approach.

Surprisingly, one subject that didn’t emerge as a discrete option for a New Zealand exhibition was The Group, a band of young reform-minded architects who emerged out of Auckland University in the late 1940s. When it comes to replying to questions about Absorbing Modernity an exhibition about The Group would have been right on message. The members of The Group championed a no-frills Kiwi-style modernism and even issued a manifesto of their architectural beliefs – a very modernist thing to do and not at all the traditional New Zealand way.

There was a we-thought-of-it-first fervour about The Group’s call for an architecture that expressed New Zealand-ness. It was rather innocent, even if to someone like Ersnt Plischke, the accomplished Austrian architect who emigrated to New Zealand in 1939 with his Jewish wife, it seemed naïve. Plischke knew where the rhetoric of national solutions could lead.

Although The Group did not get a starring role in Venice, it did get a bit part in the New Zealand exhibition staged at the Biennale. The commissioner of the New Zealand exhibition was Unitec professor Tony van Raat, and the exhibition – the winner of the Institute of Architects’ competition – was produced by a team led by Auckland architect David Mitchell.

Mitchell named his exhibition “Last, Loneliest, Loveliest” – a description given to Auckland by Rudyard Kipling in a poem about British colonial cities. In response to Koolhaas’ theme Mitchell argued there is a tradition of Pacific architecture in New Zealand that was not erased by modernity. For Mitchell the survival and evolution of this tradition is consistent with the wider story of New Zealand’s history over the past two centuries – a story, right from the start, that has been about cultural exchange, rather than absorption.

Mitchell explained his thesis like this: “The Pacific has a great architectural tradition, although hardly anyone honours it. That might be because it is not like European architecture, which is solid and massive and looks permanent. Pacific buildings are timber structures of posts and beams and infill panels and big roofs. It’s a lightweight architecture that’s comparatively transient.”

This building tradition was carried by migratory voyagers through the islands of the Pacific, arriving in these islands with the Maori. The sea-borne tradition “survived European colonisation and has adapted to modernity, rather than being subsumed by it,” Mitchell says.

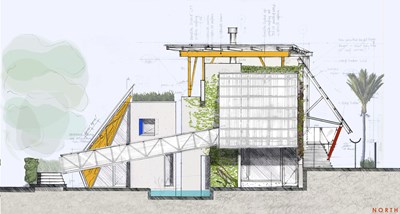

Mitchell believes not only that this evolved lightweight Pacific tradition is what makes our architecture different but that it is also what should give us optimism about our architectural future. “Given the world’s concerns about climate change and the sustainable use of resources, and New Zealand’s own worries about its seismic circumstances, the Pacific architectural qualities of resilience, flexibility and reparability have a lot to offer,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell’s Venice exhibition was influenced by his own experience of long sailing voyages through the Pacific. He and his partner Julie Stout – also a member of the exhibition team – spent years in the Pacific in the 1990s. “We saw and went into buildings that are Pacific buildings, made of sticks and thatch,” he says. “We liked them; they were architecturally interesting to us.” Here’s one of those buildings they visited: Leo’s House (gallery below, or click links to see images), in the Louisiade archipelago, Papua New Guinea, sketched by Mitchell in 1993. This was the third house Leo had built for himself; at that time, Mitchell says, he couldn’t help thinking that he hadn’t built one house for himself.

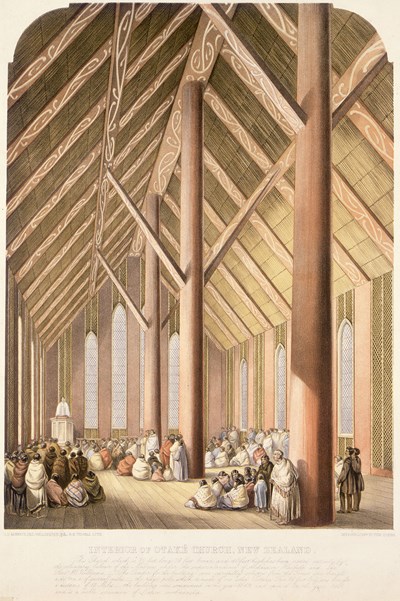

This is one of the scores of images which Mitchell used to illustrate his exhibition theme. The structures and buildings he showed date back to the contact period in the Pacific: a pa site in New Zealand in the 1830s, for example; a fale in Apia, drawn in the 1840s; and Rangiatea in Otaki, which could have passed as both a Christian Church and a Maori meeting house, here portrayed in the 1850s.

It’s interesting to compare Rangiatea with a church built a century later – Futuna Chapel, here photographed in the early 1960s. A formal marriage of church, meeting house and tent – it’s no wonder the building resonates so strongly with New Zealand architects, who are apt to cite it as this country’s most singular work of architecture.

In a way, Mitchell set out to subvert the architectural relationship expressed in this photograph, taken in 1929. It shows the interior of the just-built Auckland War Memorial Museum, with the meeting house Hotonui preserved, or incarcerated, inside it. In other words, the photo shows a building that could only have been from here contained inside a building that could have been from anywhere. Mitchell’s use of this image also reminds us how slow Modernism was to arrive in New Zealand. The museum would have been right at home in the nineteenth century.

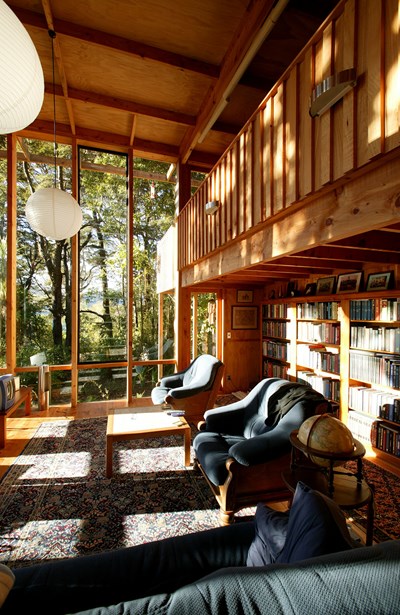

Mitchell traced his argument for a New Zealand-accented modernity through the post-War development of this country’s timber architecture. Here’s the Millar House designed by The Group’s Bruce Rotherham, and built in 1953; and the Manning House, designed by Jack Manning, built in 1960.

Skipping forward, here’s the Heke Street House, designed by Mitchell and Julie Stout, built in 1990; the Clifford Forsyth House, designed by Patrick Clifford, built in 1995; the Motorua Island House, designed by Pete Bossley, built in 1999; the Samurai House, designed by Gerald Melling, built in 2004; the Piha bach designed by Herbst Architects and built in 2011.

And the Narrow Neck House, the second house David Mitchell and Julie Stout have designed for themselves – David has been catching up with Leo. The house is near the picturesque Auckland suburb of Devonport, and it of course shocked the neighbours when it was built in 2008. It’s architecture, but not as Devonport has known it.

Many of Mitchell’s exemplar houses are in Auckland, but he pre-empted suggestions of pro-Auckland and even pro-timber bias by pointing to South Island concrete buildings that looked almost like they’d been crafted from wood – buildings such as Peter Beaven’s Lyttelton Road Tunnel Administration Building from 1964, and Miles Warren’s Student Union Building at Canterbury University, built in 1967.

Whatever criticisms could be leveled at Mitchell’s exhibition at the Venice Biennale – perhaps it overstated the Pacific influence, perhaps it was a north of New Zealand view of the country’s architecture, perhaps its was too romantic and even too hopeful, and one critic even accused Mitchell of arrogantly appropriating Pacific culture – it did have the virtue of intellectual coherence. It addressed Koolhaas’ Biennale theme and made a defensible case for the existence of a Pacific-inflected New Zealand way of doing architecture. In Venice, it turned out, we had something to say about who we are.

And here’s how we said it: The New Zealand exhibition was staged in this building – a palazzo that has stood alongside a Venetian canal for almost as long as there have been people in New Zealand. The centerpiece of the exhibition was a tent-like form with fabric sides imprinted with images showing the Pacific architecture story. To one side, a panel showed Pacific migration routes; at the front was a whatarangi, a single-poled pataka or storehouse, carved for the exhibition. In a piece of role reversal, the whatarangi contained a model of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

At the rear a tower made of post-tensioned timber – a building method being used in post-quake Christchurch – supported models for a Pacific-themed development of the Auckland waterfront. Flanking the tower were panels presenting two recent New Zealand buildings of lightweight persuasion: the extension to Auckland Art Gallery, and the Christchurch Cardboard Cathedral.

Enough about us – how were other countries represented at the Venice Architecture Biennale? How did their exhibitions deal with the challenge of saying something meaningful about a century of modernity and its impact on the their country’s architectural identity? I’ll look at some of these national responses – in alphabetical order (for no particular reason).

Austria

The Austrian pavilion was a very well executed example of the keep-it-simple approach to a Biennale exhibition. Standard 1:500 scale models of the world’s parliament buildings expressed the national ambitions (and nationalistic tendencies) of more than 150 countries, and the changing styles in which state power has been architecturally expressed over the past two centuries. This was show, not tell: the models, like the buildings they represented, spoke for themselves. One of the biggest scale models – much bigger than nearly all the others – was that of the Australian Parliament in Canberra. It’s almost as big as the MCG.

Bahrain

At the Bahrain exhibition thousands of free copies of a generous catalogue, were stacked high – with Gulf State largesse – on circular shelves, which surrounded a round table imprinted with a map locating 100 Arab buildings. The catalogue traced the architectural history of the transnational ‘pan-Arab project’, which had a lifespan coincident with the rise and fall of modernism in the region. Over the past hundred years, Arab countries first had vernacular buildings, then colonial buildings, then imported modernism, then local adaptations of modernism. Now architecture in the Gulf States, as Bahrain’s text in the official Biennale catalogue frankly put it, is an expression of real estate development and a form of neo-liberal economics.

Brazil

Brazil had no trouble finding 100 buildings to illustrate its survey of 100 years of modernity. Unlike many of the developed countries – like New Zealand – Brazil has never been squeamish about modern architecture. New Zealand’s Creative Director, David Mitchell, said the Brazilian exhibition resonated with him “because Brazil is New World, and exotic, and embraced modernity with verve.” The exhibition illustrated the point that Brazil’s architecture is modern architecture, and modern architecture is part of Brazil’s identity. As the title of Brazil’s exhibition indicated, in that country modernity is a tradition. The exhibition did suggest though that Brazil feels it hasn’t received the international critical acknowledgement its modern architecture deserves.

Canada

Canada’s well-curated exhibition presented modernity “pushed to its limits” in Nunavit, the country’s most northerly territory. The exhibition consisted of engaging models of buildings and communities in a large Arctic region occupied and governed by Inuit. The question is: will architecture in this harsh environment prove to be as adaptive and resilient as the human population? The exhibition provided grounds for optimism. It also seemed consistent with Canada’s national image as the benign occupant of a challenging landmass and a genial international citizen.

France

Perhaps surprisingly, the French exhibition was witty, honest and without hauteur, although the country’s entry in the official Biennale catalogue did point out that “since 1914, France has not so much ‘absorbed’ modernity as shaped it”. Which puts The Group’s modernising ambitions for New Zealand architecture in modest perspective. In France’s exhibition, modernity’s menace was represented, amusingly, by a large model of the sterile and hostile modernist house in Jacques Tati’s 1958 film Mon Oncle, and chillingly, by the 1942 Drancy housing estate outside Paris, which no-one wanted to live in and so which served as a Nazi internment camp.

Germany

And speaking of Nazis…The Germans know all about architectural expressions of national identity. Their Biennale exhibition was a pavilion within a pavilion: the modest, democratic 1960s Chancellor Bungalow – the former official residence of the German head of state in Bonn – was recreated in the pompous German Pavilion in the Giardini, which had been modified during the Nazi era. Because of this, the pavilion is controversial, and it was the subject of another German exhibition at the Biennale which presented alternative options for rebuilding or altering the building.

Great Britain

Some Biennale exhibitions showed architecture, others were shows about architecture. The British exhibition was in the latter camp. It was called A Clockwork Jerusalem – a bit of Anthony Burgess, a bit of William Blake – and it was a high-concept exhibition that recaptured the optimism of now-maligned post-War British modernism, presenting the architecture and town planning of the time as a liberalising movement influenced by the British traditions of the picturesque and the pastoral, and affected by a sort of Swinging London pop sensibility. The exhibition showed how comfortable the British, or English, are with the forms of pop culture. And how uncomfortable they remain with architectural expressions of modernity.

Greece

The spread of modern architecture, and modernity, in Greece was coterminous with the growth of mass tourism. As Greece’s exhibition showed, much of the Greek coastline was reshaped, for better or worse, in the post-War decades as tourism became the golden goose of the Greek economy. Koolhaas’ theme of ‘Absorbing Modernity’ is especially resonant in Greece, where economic performance, debates about national identity, and tentative moves towards sustainable development, have been given concrete expression in the country’s architecture.

Israel

In the Israeli exhibition, programmed machines inscribed patterns of settlement on beds of sand – a graphic representation of the top-down planning of 1950s Zionist modernism that treated the land as a “tabula rasa”. Hundreds of new “urburbs” – from-scratch towns created by an essentially anti-urban political movement – sprung up in a decade. The elephant in the room housing this clever exhibition was Palestine for, of course, the land upon which the Zionists built Israel was already occupied. The omission was so obvious that you had to wonder whether, in an official exhibition of a nation still pursuing a controversial settlement programme, some point was being not so subtly made. As the Israeli entry in the official Biennale catalogue stated, “there still remains an enduring demand for new and newer New Towns”.

Japan

Japan’s exhibition was as packed with stuff as a two-dollar shop. Visitors could rummage their way through thousands of plans and drawings and around hundreds of models and other artifacts. The material particularly illustrated projects and research from the 1970s, a period of experiment for young Japanese architects who went out into “the real world” in search of new directions after modernisation had seemed to reach an impasse in Japan. But if they left Japan the young architects still seemed very Japanese – drawings remained works of art, and materials looked like artworks.

Kosovo

The creators of the Kosovo exhibition were probably very sympathetic to Koolhaas’ focus on architecture rather than architects because, it seems, architects have done Kosovo few favours over the past 50 years. And nor has modernity. The Kosovans took an architecture-without-architects approach in their exhibition, stacking hundreds of models of an age-old type of Kosovan chair into a small tower. Inside the cocoon of chairs, a visitor got the point: while modern architecture has served to erase Kosovan national identity, traditional folk furniture might yet preserve it.

Nordic Countries (Finland, Norway, Sweden)

A combined exhibition by Finland, Norway and Sweden was staged in the Nordic Pavilion, the best work of architecture in the Giardini. The exhibition captured one of the most hopeful of all modernist encounters – the meeting of Nordic architects and African nation builders. For two decades from the early 1960s newly independent nations such as Tanzania, Kenya and Zambia turned to architects from the Nordic social democracies to design infrastructure projects. These architects were chosen because their countries were free from the taint of colonialism attached to other European nations. The exhibition told a story that deserved a good telling.

Poland

The Polish pavilion was the outstanding example of an exhibition which reduced an era to a moment. The exhibition did not merely focus on just one building; its subject was one part of one building: the canopy – recreated in 1:1 scale – above the burial crypt, in Krakow’s Cathedral, of the Polish war leader and ruler, Marshal Jozef Pilsudski. The canopy was created in 1937, during the brief period of Polish pre-War independence, from captured materials: jade from a demolished Russian Orthodox cathedral and steel from Austrian guns. As the excellent exhibition catalogue pointed out, this was modernism at its most morbid. The structure was a shrine to a dead leader and an expression of national identity; a provocation to Poland’s enemies and a premonition of impending disaster. Heavy stuff: it’s a wonder the canopy didn’t collapse under the weight of its own symbolism.

Serbia

The Serbian exhibition was a gold-papered room into which you groped your way via corridors of dark curtains in a blacked out pavilion. Welcome to the Balkans. The uncertain journey to the gold box was just long enough to induce mild paranoia: am I lost, will I fall, who’s coming up behind me? And what’s waiting ahead? The hidden architectural gems of Serbia, it turned out: 100 objects and elements from a hundred years of Serbian and Yugoslavian history. Getting to know us might be difficult, but you will be pleasantly surprised, seemed to be the message.

USA

The American exhibition was all about the export of American architecture, and therefore, whether intentionally or not, a demonstration of American power and global reach. The exhibition was a repository of information about scores of projects designed abroad by US architecture offices in the period 1914-2014. As with so much to do with America, the confident plenitude was overwhelming. Architecture is us, the exhibition declared. We are ubiquitous, and so is modernity: resistance is futile.

There were 50 other pavilions at last year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, and they all deserve note, but I think I’ve showed enough to suggest the flavour of Koolhaas’ event. The exhibitions could have been bewildering in their variety but instead they were strangely familiar, and even predictable, in their content and approach. Challenged to define the architectural identity of their countries over the past hundred years most of the creative directors came up with unsurprising options. To take the exhibitions I’ve just shown, what might a visitor have learned – or re-learned? – from going around the Biennale?

The Hapsburgs are long gone, but the Austrians are still obsessed with monuments.

Bahrain and the Gulf States are so rich they can build anything they like.

Concrete buildings look great in Brazil.

Canada is a big cold and competent country where people live in some very remote places.

The Nazi past still casts a shadow over Germany.

France thinks it can contest the ownership of modernity with the United States.

Great Britain puts on a good show but hasn’t got much of an appetite for change.

Modern Greek architecture shows what happens when you build an economy on tourism.

In Israel the facts that matter are the facts on the ground.

Japan has quite a different aesthetic to everyone else.

Kosovo would rather forget modernism and modernisation, and maybe even modernity.

The Nordic countries are much nicer than other European countries.

Poland is tragic.

Serbia is scary.

America is everywhere.

And New Zealand? A case can certainly be made, as David Mitchell believes, that the only thing that distinguishes our architecture – against other architectures – is its Pacific provenance. Unfortunately, attempts to pursue a fusion or crossover architecture, one that is both Pacific and contemporary, haven’t been that convincing. Perhaps the problem is that there has only been one John Scott.

I don’t think we should be too hard on the people who created national exhibitions at the Venice Biennale. Clichés, after all, are clichés for a reason – that is, they contain an element of truth. Rem Koolhaas, who is such an avant-garde architect, followed a rather conventional Biennale course: narrative history.

The creative directors of national exhibitions were asked to make sense of a century of history. What this did was encourage them to locate architecture in its cultural and even political context. Paradoxically, a Biennale that hoped to discover signs of the survival of national architectures showed instead how fraught the search for national identity can be. For many people and many countries the last century was a hard century, and a lot of the grief has been caused by movements that focus on national identity to promote aggressive nationalism.

In a sense, Koolhaas’ very interesting Biennale was a valuable-clear-the-decks exercise. Perhaps it served to get the issue of national identity in architecture out of our system. That doesn’t mean we now have to surrender to globalisation – get used to a future where architecture is the same everywhere. But maybe the way to avoid that fate is to design buildings that do not try too hard to say who we are, but that respond to far more specific particularities of circumstance and opportunity. In other words, produce more buildings in the spirit of Futuna Chapel: brave, complex, idiosyncratic and inventive. Actually, isn’t that what we want to be?