This essay was highly commended in the Open category of the 2024 Warren Trust Awards for Architectural Writing.

Honour and Control: New Plymouth Barrett Street Nurses’ Home

by Elizabeth Cox

High on a hill in New Plymouth, a building sits decaying, suffering from arson, vandalism and water damage. Its legal situation is complex. Despite this, the Barrett Street Nurses’ Home is resonant with multifaceted women’s stories — stories of those who planned, campaigned and fundraised for the building, those for whom it was built to house and to memoralise, those who controlled the spaces, and those who were controlled within it.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the life of a hospital nurse was extremely challenging. Nurses were inculcated with ideas of discipline and service. They worked seven days a week with minimal leave and were required to live in special hospital nurses’ homes, even when off-duty. Marriage wasn’t an option for those who wanted to continue to nurse, as it meant leaving the nurses’ homes, and thereby the control of the hospital.

By the First World War, the living situation of the nurses working at New Plymouth’s Barrett Street Hospital was dire. Not all could fit in the small nurses’ home provided, so they often slept in decrepit cottages or a building attached to the TB annexe. On one occasion, some came home to find their cottage had been requisitioned for diphtheria cases and all their belongings outside. In another, the nurses shared bathrooms with infectious patients, and had to prepare meals in their bedroom.

In July 1916, all 31 nurses signed a petition calling for better accommodation, conditions and pay — a rare public complaint in their highly regulated profession. The Hospital Board Chair was unsympathetic; he was ‘disgusted’ nurses would complain during wartime. However, senior doctors supported the nurses, emphasising the impact on their health, disease prevention, and training. The public and media became involved, leading to heated hospital board meetings. In August 1917, the entire senior medical staff resigned in protest. A month later the situation flipped, and the entire board resigned instead, and the doctors remained.

New Plymouth’s ratepayers elected a new hospital board, sympathetic to the nurses, and it commissioned architect Frank Messenger, of the firm Messenger and Griffiths, to design a new nurses’ home. The board sent the hospital’s matron, Beatrice Campbell, on a tour of nurses’ homes around the country. She came back with ideas which influenced Messenger’s design: the nursing journal reported her interventions “included the many conveniences which women chiefly appreciate”.

Dr Joseph Frengley, the Acting Inspector General of the Hospitals Department still didn’t believe the work was warranted, but after a visit to New Plymouth, altered his position. His new opinion was not caused by concern over the nurses’ welfare, but the difficulty of maintaining control over them. Nurses scattered over five locations was ‘an arrangement subversive to discipline’ and, he claimed, parents were unwilling to let their daughters take up nursing, as the board couldn’t guarantee they would be under proper control.

At least 19 New Plymouth nurses served overseas in World War One. Three were on Marquette, when it was torpedoed in 1915, with the loss of 10 nurses and 157 others. Then in November and December 1918, the city was devastated by the influenza epidemic, with 2,700 cases and 81 deaths in hospital. Nearly every New Plymouth nurse contracted the disease, and four died. The devotion shown by the nurses during this period made the community intolerant of any further delays, and tenders for the nurses’ home were finally issued in December 1918.

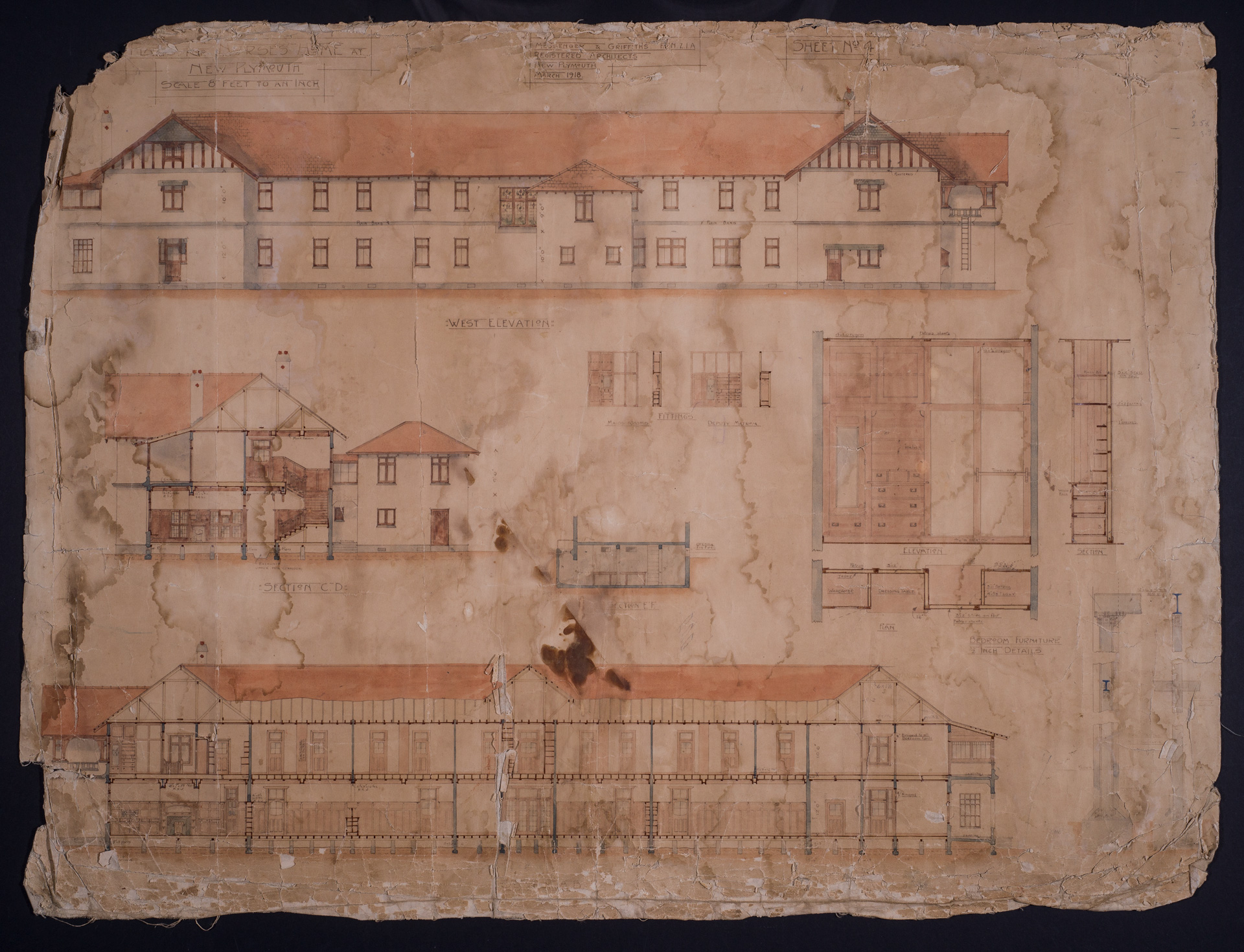

The building was constructed with roughcast concrete over structural reinforced concrete walls with Marseilles tiles on the roof, in an Arts and Crafts style. Its two floors were in an H-shape plan, with central corridors, large balconies, 55 bedrooms, dining and sitting rooms, lecture halls and study areas.

Two significant changes were made after construction had begun. In April 1919, only six months after the war ended, a member of the community suggested that a War Memorial Hall could be added to the nurses’ home, to honour the New Plymouth soldiers and nurses who had fallen during the war and the epidemic. The Board agreed, provided the community raised the funds, which it did, including a house-to-house collection by the Old Girls of the local high school. It was the first war memorial proposed in New Plymouth. What is more, it was one of very few ‘useful’ war memorials, such as halls, bridges or libraries, ever built in New Zealand after the First War World. This is therefore a nationally significant space.

The other change made during construction was suggested and paid for by the nurses themselves. The architect had specified coloured concrete floors and walls in the bathrooms and kitchen block to save money. Experience in other hospitals had shown how difficult this was to keep clean. Mindful of hygiene, and future epidemics, the nurses fundraised to pay for ceramic tiles for the walls and floors – going out onto the streets to collect from the public on what they called a ‘Nurses Saturday’.

The new nurses’ home opened in March 1922. It was a highly controlled space. The hospital’s matron was in charge of the home as well as the wards – putting her in charge of the nurses during both their living and working hours. It was run with military-like discipline. Nurses wore uniforms even when off-duty; the dining room seating and bedrooms were organised by seniority. Curfews were rigidly enforced, and breaches resulted in ‘gating’ (cancelled leave). One nurse who entered the training school in 1927 recalled her first day off was in 1930, at the time of her final exams.

Graduation balls, an important part of the annual calendar, were held in the war memorial hall, with its sprung dance floor, dark beams, and stained-glass windows. These were closely supervised by the matron, and the name of the proposed male dance partners had to be submitted for approval in advance.

All this did nothing to break the spirits of the young women who lived there, and sneaking back into the building after curfew via the fire escapes was legendary, and fondly remembered. One history of the home noted the long-suffering nursing sisters in charge of the home and their “constant battle with young women bent on proving the old adage that rules were meant to be broken”. Despite the rules, many nurses fondly recalled the camaraderie, social clubs and lifelong friendships formed there.

The nurses’ home grew, eventually housing 190 bedrooms within four additions. It became a prominent building in the city, earning the nickname ‘the palace’.

In 1981, the new Base Hospital superseded the Barrett Street Hospital, and the complex instead housed legal and illegal tenants until 2012, when it was evacuated due to earthquake concerns. All of the other buildings in the complex have now been demolished.

In the derelict nurses’ home, the ceramic tiles still remain on the walls and floors, although now smashed by vandals. And since the town unveiled another First World War cenotaph in 1924, also designed by Messenger (this came in the government’s preferred style of ornamental statuary), there would be virtually no-one in New Plymouth today, if you asked them to name the city’s war memorials, who would name the memorial hall in the crumbling building up on the hill.

Honour and Control: Part Two

Since 2012, the building has been standing empty, more dangerous and damaged by the day. Land Information NZ is its controlling body, and is meant to be caring for it, until its future can be resolved.

The building sits on Otumaikuku Pa, a place hugely culturally important to Te Atiawa, and one of the few places that were supposed to be reserved for Māori in the future town of New Plymouth, as part of the highly dubious ‘purchase’ of the land, by the unsavory William Wakefield. The Otumaikuku Reserve was illegally alienated from Te Atiawa, and the hospital was built on that land. Now, Te Atiawa has a chance to get a tiny portion of their land back as part of their Treaty settlement, but on part of it sits the home. And in turn, on the home, sits a heritage listing.

Such a listing is an honour, certainly, but also a form of control. As Dion Tuuta, pouwhakahaere of Te Kotahitanga o Te Atiawa, says “None of us have been served well by the Crown’s stewardship of this particular property. They’ve allowed it to fall into wrack and ruin... as part of the Treaty settlement [they have] handed it over to us as a community to sort out and, you know, that’s going to be an interesting and probably challenging discussion.”

Community efforts to save it from demolition are often spurred by the women who once lived and trained there. How do we honour their stories, and other heritage stories ties up in the building, and also the stories and the struggle of Te Atiawa to control their own future and exercise mana whenua over their precious land?

Image: Architectural plans for the proposed Barrett Street Nurses Home at the New Plymouth Hospital. Drawn in March 1918, by architects Messenger and Griffiths. Image courtesy of Puke Ariki, ARC2013-1555.