This essay was highly commended in the Open category of the 2024 Warren Trust Awards for Architectural Writing.

Kōrero Kamaka

by André Prichard

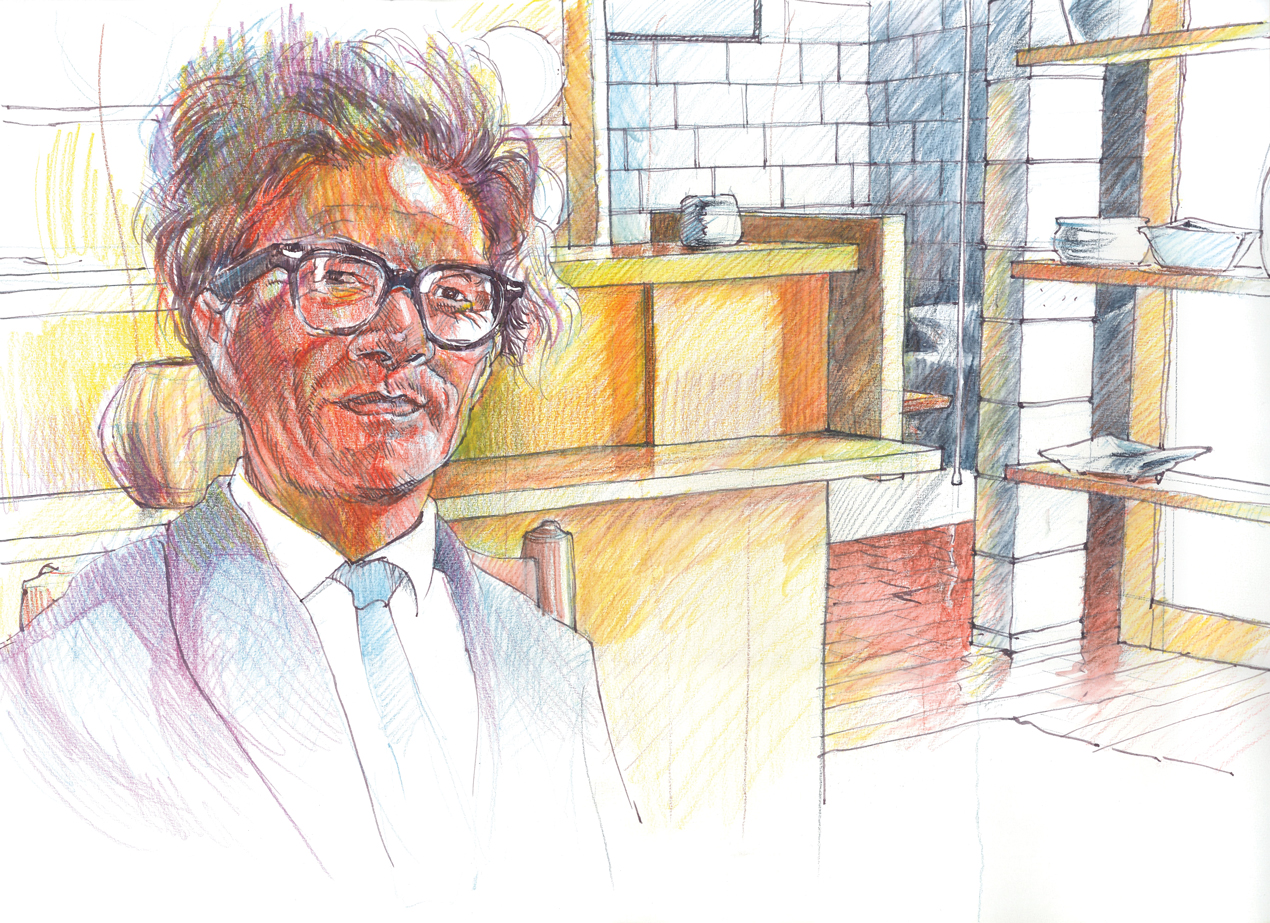

Illustration by Dennis Chippendale

Some buildings dominate the narrative. They barge in, bluster, suck up space. Others are content to nestle in the background, auxiliary and overlooked. At the Martin House, located on the rural outskirts of Hastings, it is the Pottery that asks, modestly, to be noticed.

The structure is situated on the right as you follow a long gravel track to the house. A shaded lawn sits in front; abundant tōtara and akeake seem to camouflage. At the same time, on the left, a pond insists ‘look at me.’ Then you emerge into the heart of the property and it is the eponymous house – perched atop a rise, striking and sublime – that takes your breath away. The Pottery retreats still further.

Commissioned on a bare 10-acre block by potters Bruce and Estelle Martin in 1970, the Martin House, Pottery and Kilns are today a Category 1 Historic Place. But they are also functional: a home, a workshop and display rooms. When John Scott designed the buildings, it was a manufacturing business – albeit a cottage one – he was responding to, not just a place of residence. The Martins’ site gave them space, utility and, just as importantly, distant neighbours unlikely to complain about the acrid smoke from their diesel-fired kiln.

When Bruce and Estelle christened the Pottery they chose the name Kamaka. In Japanese this means flower, fragrant or, sometimes, truth. It can also be a cauldron, a crucible if you like. In Te Reo Māori, kāmaka means stone.

The building itself is compact: 96 square metres encompassing a space to fix, to throw, to store and to show. It comprises half a dozen discrete spaces, defined by a rhythm of alternating monopitched and box-like forms. The construction, like that of the house, is breeze block, spartan and serviceable. Industrial grey, the colour of unfired clay, characterises the walls and floors. Black Douglas fir rafters support a particle board roof, while high clerestory windows flood the larger spaces in light. The smaller forms are, in contrast, intimate, almost gloomy. The final gallery, added in 1978, is a comparatively flamboyant gesture, brightly glazed through a wide window cantilevered to display pots.

When the census woman came to the house last year, she almost missed it. “Oh, does someone live in there?” she asked as she was leaving.

“No,” I replied. “It’s just a workshop.”

Before the house was finished, Bruce and Estelle would camp in the Pottery’s tiny showroom, content to have moved into the earliest part of the property to be finished. This is how they spent their first Christmas there. It must’ve felt grand.

As the home was completed, and the Pottery became a place of workaday labour, so it transformed. A routine of sitting at the wheel, turning clay, drying and bisquing pots, and firing in frequent batches became the norm. The workshop grew into a place of repetitive, meditative work, interrupted only by cups of tea and occasional customers. In winter the building froze and the oil heater hummed. Outside, the grounds asked to be planted in trees and spring flowers. Everywhere was hard work.

Nowhere shows this quite like the storeroom out the back, a dark alley crammed with the effort required to keep a commercial pottery operating. Here boxes and bubble wrap, timber and sheet metal, share space with evil-looking machines from the pre-Health and Safety past: Bruce’s drill press, his bench grinder,

his table saw. This area is hidden from the public face of the Pottery by a wide heavy door, almost always pulled tight. It seals off this unseemly, but also unseen, labour.

On Bruce’s workbench, a kink to the left down the alleyway, lies a decades-long accumulation of tools. Here heavy hammers and blunt saws are stacked like plates. Tobacco tins – brands like Kauri, Air Man and The Greys – house an assortment of screws and nails. The shadow board at the back is packed, overflowing with tools tacked like tinsel.

Over the years the Pottery itself has changed. When I first saw it, plastic tables with plumbing pipe legs precariously held pots worth thousands. It looked like a photo shoot from a 1990s edition of Home & Garden. This altered when architect Nicholas Stevens designed bespoke shelving for the space a few years ago, built by local craftsman Peter McLean. Now this part of the workshop features crisp timber ledges, in the Japanese style, with lean turned poles for legs. The pots on these – mostly Bruce and Estelle’s interpretations of Japanese tea ceremony ceramics – have names like ‘The Wreck’, ‘Crashing Waves’ and ‘Ridge of Tears’. In the right light, at the beginning of the day, the sun streams through the Lancewood outside in caressing fingers.

The demonstration of Bruce and Estelle’s effort remains in the workshop. Nodules of hardened clay cling to the large concrete tub like coral; porcelain dust nestles in the corners of window jambs. On the hardwood floor by the house-facing windows, tessellations of burnt umber signal pots, piping hot straight out of the kiln, placed too soon to be cooled. The workshop is geological stratum, it is midden.

The current occupiers – myself, my partner (Bruce and Estelle’s granddaughter) and our two young children – are kaitiaki of this place, archivists of its many stories. We tell and retell, make and remake. We have contributed too, in our way. At the moment a drum kit borrowed from a friend occupies the middle of the throwing space, a harbour for my son to thump and thwack and thrive. Lego and playdough and My Little Ponies flourish in the room. Glitter has replaced clay on shoes, in corners and under furniture.

Just a few months ago, we fired the small Anagama kiln down the back for the first time in twenty years. Hastily applied slurry, and wire and metal reinforcing, ensured it wasn’t going to implode. A handful of potters and friends joined us, and we fed the kiln for four days. The first tentative pots – grey as stone, drizzled and dripped by fire – rest in the sunlit gallery with the best of Bruce and Estelle’s work. It is a demanding legacy, but a good one.

This space, the most arresting, lies at the northern edge of the building. It is bright, airy, with a voluminous pitched ceiling like a sail. Staggering works – slab-built geometric marvels, enormous stamnoi, a perfect ceramic ploughshare based on one Bruce excavated from the land, Estelle’s delicate flower-daubed plates – slumber. Each demands your attention, to be inspected and admired. It is a space to spend hours.

On the wall at the back is Bruce’s original plan for the large Anagama, a meticulously drafted diagram with annotations in both English and Japanese. It was finally built in 1982. Master potter Fujii Sanyo helped, ensuring the monster kiln would work. A stack of Peter Shaw’s books about the Pottery reward the most curious visitor. Everywhere is a story.

Back in the workshop, relics of Bruce and Estelle’s life ensure they are never too far away. In the 1940s Bruce took a picture of his new bride, looking like Katharine Hepburn in moody silhouette. He developed the print himself, in a dark room not unlike the one hidden in a spider-webbed nook of the storeroom. This portrait rests atop a rickety shelf, next to Bruce’s ashes. When he died last year we placed them together, our own makeshift memorial. Around the ashes two dark red bandanas are tied, one each, worn by them to ward off the immense heat of stoking. They are looped around the box in twin rings, eternities.

And so, the workshop continues. Previously, as Bruce aged into his nineties, the place stilled, petrified. It was very silent. Now it draws breath once more. Hefty bags of pottery clay, alumina and lime promise some new, former life. It is a place of rebirth.

For a pot to fire well it must survive great hardship: tons of wood, diminished to ash, temperatures in the thousands, many days of firing. The risk of collapse, or explosion, is ever present. Only the carefully choreographed dance of oxidation and reduction stops the pots from failing. When done well it is the natural glazes – unique, alchemical, magical – that indicate success.

A building, especially a craftsperson’s workshop, is not dissimilar. The architect must balance form with function, practicality with design. They must manage, faithfully, the utility of the building with dimensions that both stir and uplift. It is pragmatism and it is sorcery.

The Martin Pottery may not boast like the house, but it most certainly speaks. It is a muted voice, spoken in block and glass, in clay vessels and containers, many years in the telling. A story simple and survivable as stone, kōrero Kamaka.