'An Island in the Bay' by Michael Davis

Architect Michael Davis details his experience of a run-down community centre in Wellington, and dreams of how much better it could be.

In concluding his 2005 essay Into the Post-War World, the late architect Bill Toomath observed: “In my post-war period a main focus was on community buildings and modestly economical family houses. Yet, in the past decade, five of the nine ‘Home of the Year’ awards made by a national home-maker’s magazine went to lavish holiday houses for the well-to-do.”

Every second Friday my daughter goes to the Island Bay Community Centre to attend a group for young adults with intellectual disabilities. My experiences of the building range from drop-offs and pick-ups, to attending birthday celebrations, farewells and Christmas functions.

Like many such centres, this building is an important asset to the people of Island Bay and nearby suburbs, and is popular because it offers spaces for an eclectic variety of groups and activities. These include religious and cultural groups, a book club, a Narcotics Anonymous group, yoga, Pilates, Tai Chi, and a range of dance groups – all reflecting the diverse demographics of the community. These are supported by committed volunteers and part-time paid staff.

The centre interests me because occasionally I give some thought to imagining what it could be like if it received the same level of ‘investment’ as some of the infrequently occupied holiday houses we see winning awards and gracing the pages

of architectural magazines.

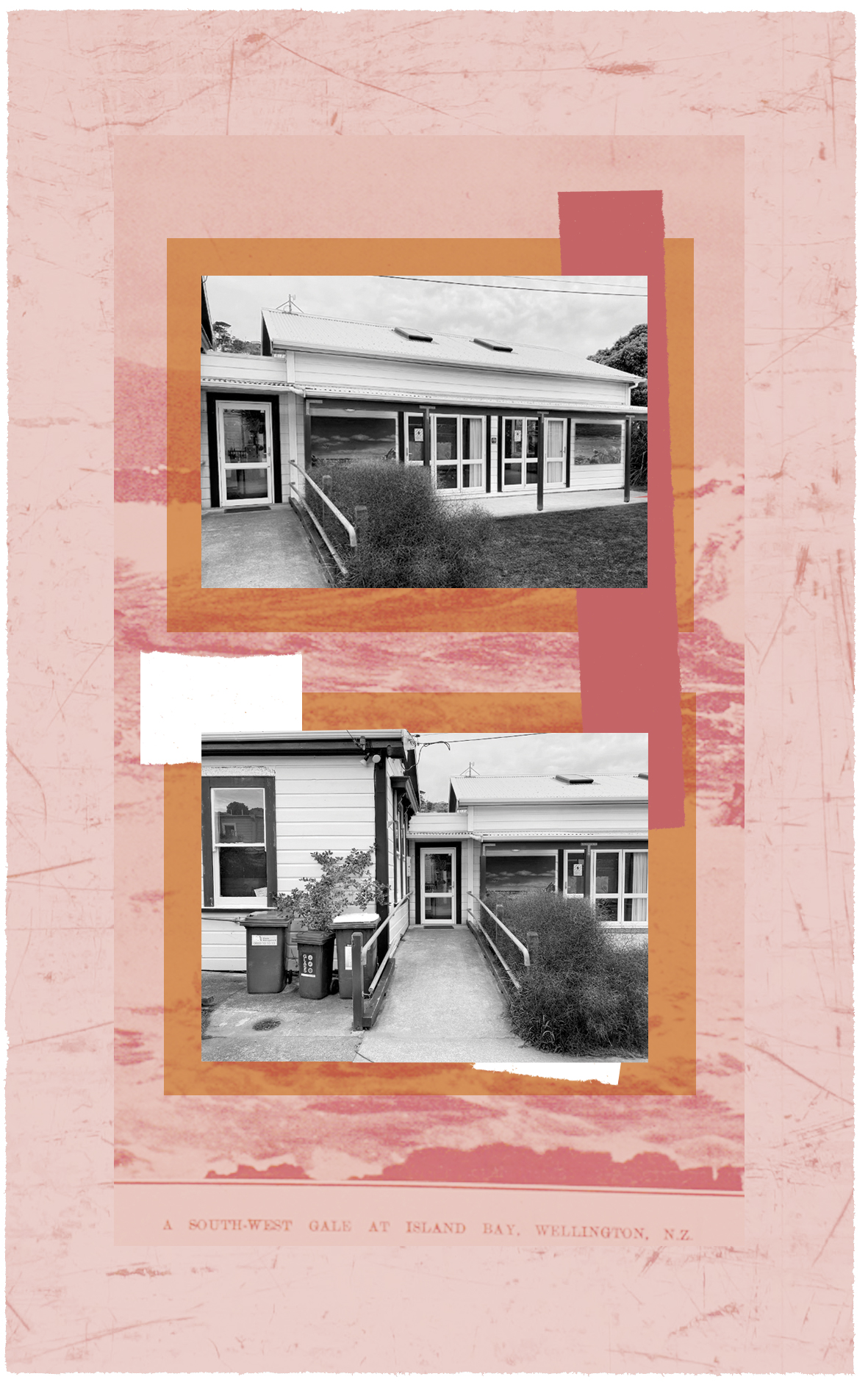

The centre is tucked down a driveway between some shops on the main street of Island Bay. The only indication that it’s there is a modest sign fixed to the side of a neighbouring takeaway shop. The asphalt is in poor condition and, because there is no lighting, some kerbing to an adjacent property is a trip hazard that occasionally damages visitors’ vehicles. While there is a separate pedestrian entry nearby, this main entry, with parking for five cars including an accessible park, has no clear delineation for pedestrians.

Despite these shortcomings, the centre is very popular.

Following the demolition of two earthquake-prone shops, the new Community Centre has a highly visible location on The Parade. As well as convenient street parking and a bus-stop outside, there is access to a well-lit landscaped car park behind.

From the car park you can now see the Community Centre. Yellow painted lines on the asphalt and a gap in some bushes signal the way into the property. The building is an early 20th-century villa, to which a simple gable-roofed hall has been added. There is a concrete path that bisects a lawn. Sitting in the middle of one section of lawn is a sadly weathered timber picnic table, and some stone carvings have been randomly placed. There are several doors opening off the hall and the villa so it is not immediately apparent where the main entry is.

Continuing on the path, you come to a point where two accessible ramps meet. One is no longer in use, evidenced by rubbish bins parked at its base. The other leads to what appears to be the entry – a single outward-swinging door. The ramp handrails are unpainted galvanised steel and the width is little more than Building Code minimum – it is often unpleasantly congested in this area at drop-off and pick-up times.

Despite these shortcomings, the centre is very popular.

The double-height scale of the centre sits well with its neighbours, and the landscaped setback suggests that this is a special building – giving something back to the street. There are small details that say something about the community including a carved pou, a weathervane in the shape of a fishing boat, and a generous number of bike parks. The ideas and design of these were informed by a participatory design process. Set between two areas of native planting is a wide section of gently sloping stone paving leading to the double entry doors, sheltered by a broad canopy. There is some built-in hardwood seating where people can wait under cover, with a view of the street.

Once inside, there is a small lobby space dominated by a Civil Defence cupboard and a table with lots of pamphlets laid out. This area gets very congested and is unpleasantly hot in the warmer months. Turn right and you’ll go into the hall space with a kitchen attached; turn left and there is a narrow corridor. The hall is a basic space with steel portal frames, and some suspended industrial lights and radiant heaters. There are glazed doors on the west side but these are seldom used because there is quite a step down to a sheltered concrete area outside – perhaps they are opened for more able-bodied groups. A resilient yellow-coloured vinyl lines the walls up to door height.

To add to the institutional aesthetic, all the projecting corners are finished in an aluminium trim for protection. The wall above this and the ceiling are painted plasterboard. The hall’s functional plainness is redeemed by its natural timber floor, although the spongy feel underfoot suggests that this is actually a thin veneer. There is a sound system mounted on a corner shelf and a miscellany of posters nearby. The hard finishes everywhere make the space very reverberant and the acoustics unpleasant for some.

Despite these shortcomings, the centre is very popular.

The generous lobby space allows people to gather and look at displays of current community projects, with a super-graphic photo of Tapu Te Ranga Motu that is visible at night to passers-by. This opens directly into the hall, which has clerestory windows that bathe the space in sunlight. Some coloured glass adds drama and interest to the light quality. The space is articulated with a criss-cross of exposed timber portals with crafted metal connections.

A timber-panelled dado runs around the walls except for the north-facing, which has large sliding glass doors and a level threshold to a sheltered outdoor space. Above the dado line, acoustic panels are arranged in a colourful chevron pattern. The ceiling is comprised of stained-plywood perforated acoustic panels, and a lighting rig includes speakers. The floor is parquet with underfloor heating. At one end is a raised stage with storage space underneath.

The narrow corridor has a toilet and office off it, and leads to a modestly sized lounge-cum-meeting space, and a kitchen. These are in the lean-to of the original villa, so the ceiling height is not generous. The lounge has some trestle tables in the centre and around the walls are a piano, a stack of chairs, a sound system, some posters and several artworks. When people are sitting at the tables it is difficult to circulate around the room. Adjacent to this is a residential-scale kitchen with plain white cupboards and drawers, and spotty pale-green laminate benches. There are no kitchen facilities for those in wheelchairs and it is often very congested because of its size and design.

Despite these shortcomings, the centre is very popular.

The lounge is a large, brightly coloured space with high, north-facing windows. Next to a recess for the piano is squab seating in a bay window that gets the morning sun. There is a range of comfortable furniture to suit the needs of the groups, and the floor is finished in foam-backed carpet tiles for comfort. There is a pinnable wall surface to display artworks and information. Opening onto this is the large kitchen with timber-look cupboards and drawers, and hard-wearing stainless-steel benchtops. Children and people in wheelchairs can also use this area with its height-adjustable bench.

There are framed photos of a range of cuisines from within the community and a glass mosaic splashback sparkles in the sunlight. The other side of the kitchen opens to the street so that groups can offer food and beverages for fundraising purposes, although a café operator has expressed interest in a shared commercial arrangement.

At the back of the lean-to, double doors open to a north-facing outdoor space which is overlooked by a four-storey apartment block. There is a rough, greyed-off timber deck with two steps down to some brick paving. The only play equipment appears to be a small dinghy set into the ground but this is usually filled with leaves. There is a generous lawn area and some raised planter beds where vegetables and herbs are grown.

Despite these shortcomings, the centre is very popular.

The lounge opens out to a sunny, sheltered courtyard space with views to the hills around. There is a built-in barbecue, seating, and an outdoor cupboard where loose furniture, play equipment, and a shade sail are stored. As well as some sculptures and artworks by local artists, there is a slide and an obstacle course for children.

The centre is more popular than ever.

This essay was highly commended in the 2020 Warren Trust Awards for Architectural Writing. It is included in 10 Stories About Architecture 6, which is available from our shop.