2013 Gold Medal: Pip Cheshire

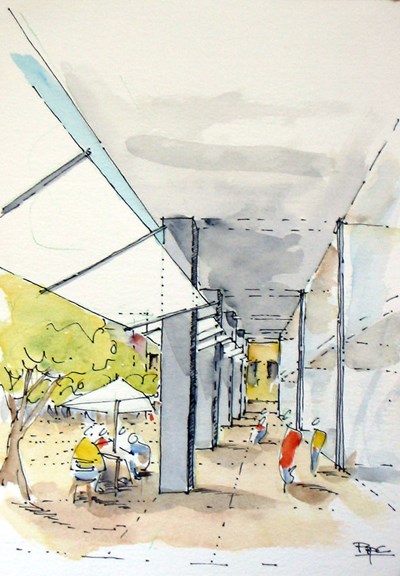

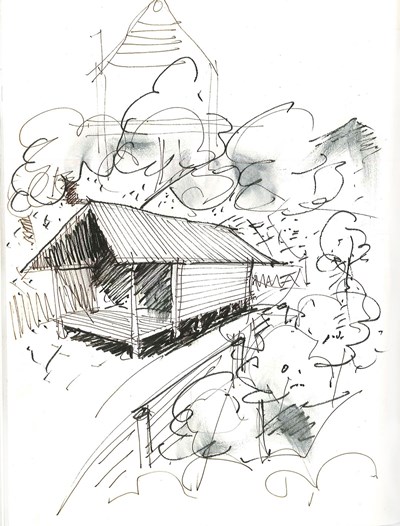

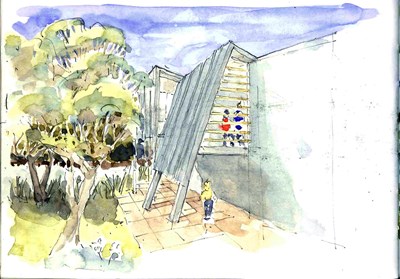

Leigh Marine Centre, Cheshire Architects

Photo by Jeremy Toth

Pip Cheshire’s architectural career, which spans three and half decades and which promises yet further development, has been propelled by a confluence of admirable personal and professional qualities: courage, adventurousness, curiosity, enthusiasm and persistence.

Pip’s intellectual honesty and integrity have directed him away from paths of least resistance, and self-belief and a necessary stubbornness have enabled him to follow a course of his own making. At key points in his career he has rejected safe choices in favour of riskier but potentially more fulfilling options. There was nothing capricious about such decisions: one of the abiding and fascinating characteristics of Pip’s career is his determination to reconcile his ambition with his desire to pursue meaningful work consistent with his personal principles.

Pip’s courtesy and collegiality co-exists with a driven nature. He was a relatively late starter in architecture – he was 26 when he enrolled in the University of Auckland School of Architecture in 1976 – and has often said he feels compelled to make up for lost time. However his earlier studies, business ventures and social activism gave him valuable insights into the political and commercial contexts in which architects operate, and have provided him with experiences that have informed the urbanity of his personality and his practice.

Eager to get his career going, Pip was fast out of the blocks. While still at Architecture School he designed The Melba [1979-80], a city restaurant that anticipated Auckland’s awakening appetite for more sophisticated social environments.

On the back of this commission, and as soon as he graduated, Pip, with some fellow students, set up Artifice, an of-its-time architects’ collective. If the genesis of Artifice revealed anti-establishment inclinations, the brevity of its life-span signaled Pip’s serious intentions. With Pete Bossley, Pip soon set up Bossley Cheshire, and the new firm quickly won a reputation for, in architectural historian Peter Shaw’s phrase, “contriving to shock the bourgeoisie while housing them”.

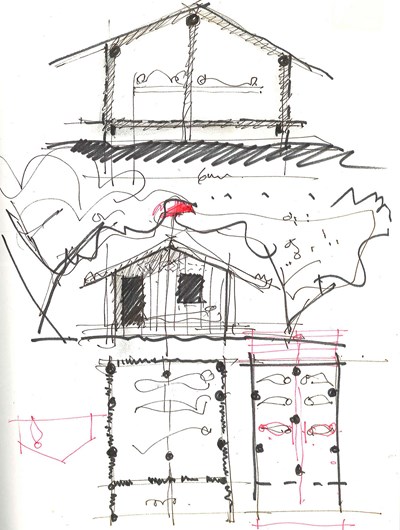

Through the 1980s, in a series of houses including the Turner House [1981], Vernon Townhouses [1985] and Markus House [1988], Pip expressed his impatience with the neo-vernacular style that had dominated New Zealand architecture in the previous decade. Pip has always been skeptical of orthodoxies and, while he has progressively moved closer in the direction of clarity of expression, he has never been afraid of complexity. Thus his architecture has never become frozen in a moment, and resists facile taxonomy.

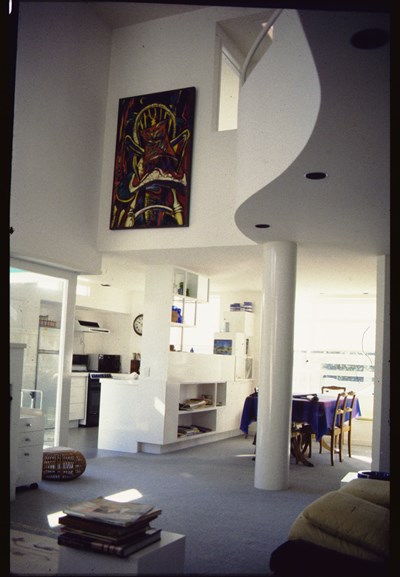

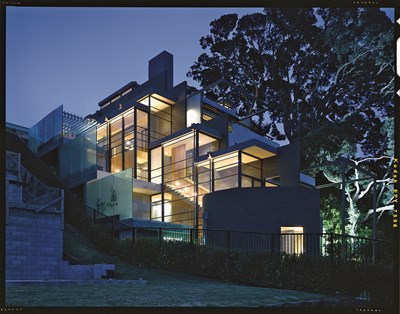

Pip’s ambition and restlessness, and that of Pete Bossley, explains the merging, in 1989, of their practice with JASMaD to form JASMAX. For Pip, larger-scale work was the lure of the alliance; JASMAX became New Zealand’s largest practice and Pip, who was a founding director of the new practice, became heavily involved in its administration, serving as managing director from 1999 until 2003, the year in which he departed JASMAX to form his own practice, Cheshire Architects. An important project Pip completed while at JASMAX was the Congreve House [1987-92, below], a resolutely solid and substantial house on Auckland’s North Shore. This house and others designed for the Congreves, and for artists Stephen Bambury [Bambury House, 1995-96] and Terry Stringer [1995-2000], and for Peter Cooper [Cooper House, 1998-2004], testify to the importance of strong client relationships throughout Pip’s career.

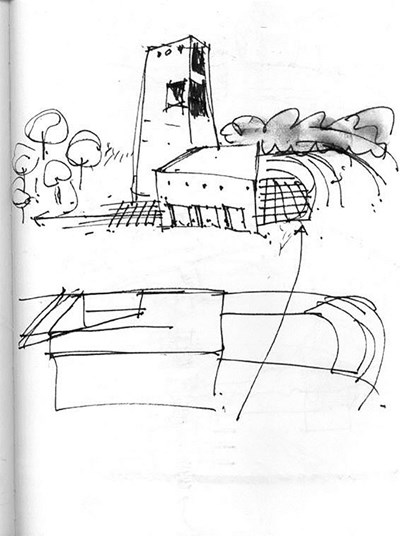

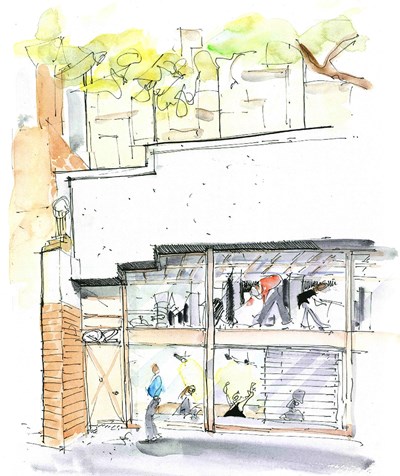

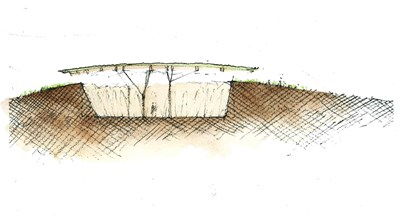

Pip has always thrived when his forthrightness has been reciprocated, his interest in ideas shared and his commitment matched. Projects such as Q Theatre, Auckland [2002-10], Britomart [2003–], the University of Auckland Marine Laboratory, Leigh [2004-11], and Marsden Cross Heritage Park, Bay of Islands [2004–], are a credit not just to Pip’s design skills but also his steadfastness and mature engagement with challenging propositions. There is so much else to Pip’s career: his heritage work in Antarctica, and his pro-bono work much closer to home; his teaching and his mentoring of generations of young architects; his writing and publishing and lecturing and presenting. His has a rich architectural career, one in which breadth of reach is equaled by quality of achievement, and one that fully deserves the award of the New Zealand Institute of Architects Gold Medal.