2003 Gold Medal: Peter Beaven

Peter Beaven in 2008

Photo by Ian Lochhead

The New Zealand Institute of Architects has awarded a Gold Medal, its highest honour, to Christchurch architect Peter Beaven. The award recognises Beaven’s outstanding contribution to the practice of architecture during his substantial career.

Peter Beaven was born in 1925, the grandson of builders on both sides of his family. Though a self-proclaimed “free spirit” from the start, he was very early influenced by the fine architecture of early Christchurch. He most admired the houses of Sumner, the buildings of his school, Christ’s College; and the fine neo-Gothic work of Benjamin Mountfort.

This love for the nineteenth century was uncommon during the Modernist years of the twentieth. But then Peter has always been his own man. With unusual confidence he embraced the construction traditions of his family and his hometown, and set about making the kinds of places people might love. Yet it was more than upbringing, desire and a respect for history that made Peter a fine architect. He has that rare gift – a lovely eye.

When, in 1963, the Lyttelton Tunnel Road building touched down on the Port Hills it had come from another land – the original mind of Peter Beaven.

It was his first significant building. For architectural students of the day it was a pilgrimage site.

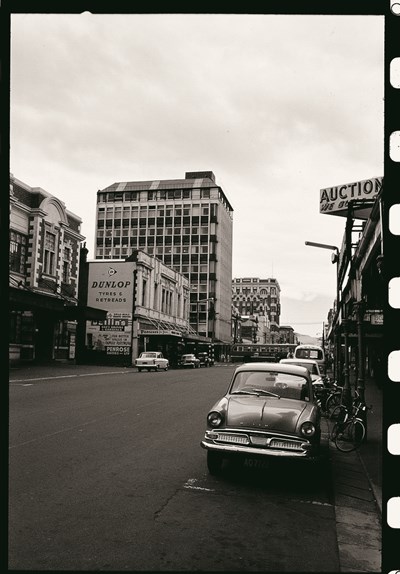

In Christchurch in 1966 Peter made Manchester Unity a model of the office building for a flat provincial city block. And in Auckland in 1967 he reintroduced, with Canterbury Arcade, an urban form that had been ignored since the 1920’s. “In a virtuoso display of planning skills he punched a staggered arcade through several buildings from Queen Street to High Street, and linked it to a tiny shaft of offices that was wedged between existing buildings encrusted with balconies and shutters and crowned with garrets.” The building makes a delightful contribution to inhabiting the city. Lyttelton Tunnel Building and Manchester Unity have subsequently won NZIA Enduring Awards.

In a life of such continuous production at a high level it seems unfair to single out certain buildings, but two more NZIA Award winners stand out. Beaven and Lovell-Smith, his engineer, made a splendid public grandstand and pool at QEII Park for the Commonwealth Games of 1974. At about the same time, the Habitat Housing scheme in Thorndon, Wellington, designed by Beaven and Burwell Hunt, spurred on the acceptance of finely scaled town living in Wellington and Christchurch.

It is the marvellous combination of observation and inventiveness that has given Peter’s buildings their distinctive stamp. Here is an architect of the greatest complexity.

Place and occasion, craft and history, social ritual and simple need, fuel his imagination. His search for a richer, humanist, socially-orientated architecture based on a romantic vision of how we all might live infuses his many houses, and most recently the Longbeach Rural School in Ashburton. This vision may yet prove to be his biggest legacy.

Anyone who spends more than ten minutes in Peter’s company knows they have met a man of passion. What a singular gift that is. Fifty years of architectural polemic has not dimmed his ardour. Peter has a long history of wading in to battles to defend or promote good civic and urban design, both in New Zealand and England where he lived and worked for ten years until 1985. He has fought successfully for the preservation of buildings – notably the present Christchurch Arts Centre, and he had a major role in the formation of the Christchurch Civic Trust.

He has written many articles and a book with John Stacpoole, rather grandly titled Architecture 1820-1970. He has spoken to countless gatherings and through all these, the buoyant enthusiasm of the man for his subject has always shone.

These days he can still be found around lunchtime emerging from his garret in the Provincial Chambers in search of kindred spirits, sailing down Durham Street like the last of the windjammers.

Peter once recounted that Mountfort’s first church when under construction, literally collapsed in a heap around him. “But Mountfort didn’t give up or turn to drink like the rest of us,” said Peter. “He charged on getting better and better.” For the same reasons we would like to salute you Peter.

This citation was written for the NZIA by Julie Stout (National Jury Convenor) and David Mitchell.