Paolo steers a clever course

'Somewhere Other', by John Wardle Architects.

The presidency of the Venice Biennale is a prestigious position and the Biennale has often been a contested site in Italy’s politico-cultural landscape. It may become even more so in the wake of the collapse of the established parties of both the right and the left and the rise of assertive populism and chauvinist nationalism. By John Walsh.

Biennale President Paolo Baratta is an adroit navigator of the shifting currents in Italian politics, and international art and architecture. A Milanese engineering graduate who became an economist and banker, Baratta held ministerial posts in centre-left Italian governments in the 1990s and then smoothly transitioned into corporate roles. Baratta is, then, a consummate insider; he survived the implosion of the scandal-plagued Socialist Party and a decade of Berlusconi’s crony politics and has benefited from the corporatisation of Italian state infrastructure assets. He is the sort of adroit and successful technocrat anathematised by the resentful constituencies who respond to Matteo Salvini in Italy (and Donald Trump in America and the Brexiteers in Britain.)

Baratta (left, with 2018 curators Yvonne Farrell and Shelly McNamara) was President of the Biennale from 1998 to 2000 and regained the office in 2008. In his role, over the last decade, Baratta has exhibited the finely attuned responsiveness to shifts in the political and cultural atmosphere developed over a long career spent in close proximity to power. Under his leadership, the Venice Architecture Biennale has tacked between theory and practice, thought and work, criticism and social engagement. The course corrections made from one Biennale to the next are signalled by the selection of the event’s director, the person who decides the Biennale’s theme and acts as its public face.

Baratta (left, with 2018 curators Yvonne Farrell and Shelly McNamara) was President of the Biennale from 1998 to 2000 and regained the office in 2008. In his role, over the last decade, Baratta has exhibited the finely attuned responsiveness to shifts in the political and cultural atmosphere developed over a long career spent in close proximity to power. Under his leadership, the Venice Architecture Biennale has tacked between theory and practice, thought and work, criticism and social engagement. The course corrections made from one Biennale to the next are signalled by the selection of the event’s director, the person who decides the Biennale’s theme and acts as its public face.

Which brings us to ‘starchitecture’ and ‘starchitects’. The obvious manifestation of the Architecture Biennale’s pirouetting around the issue of relevance is its relationship to architecture’s star system. On the one hand, the Biennale benefits from the profile of a celebrated director, and from the professional heft such a figure brings to his – or, more occasionally, her – role. On the other hand, celebrity has its downside. Since the onset of the GFC, which coincided with the start of Baratta’s second term as Biennale president, ‘stararchitecture’ has been perceived to be part of the problem. ‘Starchitects’ are associated with extravagant projects commissioned by autocratic Middle Eastern or Asian governments and, in Western democracies, by very wealthy individuals or law-unto-themselves multinational corporations. The uncomfortable truth revealed by these liaisons is that members of a profession that tends to be liberal in its social and political views and that habitually advocates for the common good is quite prepared to serve the global elite. Unless you have a hide as thick as Patrick Schumacher, the libertarian controversialist now heading Zaha Hadid Architects, or Lord Foster, the UK’s most famous architect, you’re going to be aware that this contradiction is awkwardly close to hypocrisy.

The last three iterations of the Venice Architecture Biennale illustrate all these things: the sensitivity of the Biennale organisation and its president to the current cultural climate; the oscillations between high concept and practical engagement; the treatment of ‘starchitecture’. In 2014, the director of the Biennale was Rem Koolhaas, one of architecture’s out-and-out stars, and perhaps the profession’s most self-consciously intellectual practitioner. Koolhaas called ‘his’ Biennale Fundamentals; rather ironically, the ‘starchitect’ director, in response to criticism within and without the profession of architecture’s grandiosity and wastefulness, made a stand not just against ‘starchitects’, but also against architects. His own commissioned exhibition focused not on buildings, but on their constituent parts: floor, wall, roof, window, corridor, etc. As for the exhibitions mounted in the 65 national pavilions, curators were invited to address, under the theme of ‘Absorbing Modernity’, the story of their country’s architecture in the century since 1914.

In retrospect, Koolhaas’s Biennale looks like a giant exercise in mansplaining. Not for nothing, as The Architectural Review recently pointed out, was Koolhaas a journalist before he was an architect.

After Koolhaas’s back-to-basics clearing of the decks, what next? You could practically hear the clicking of the Biennale’s zeitgeistometer; the time was right for action, not diagnosis, and the man to provide it was Alejandro Aravena, a Chilean architect whose practice includes innovative (and well-publicised) community housing projects. The choice of Aravena as director of the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale was timely; he became even more a man of the moment when, not long before the opening of ‘his’ Biennale, to which he gave the agit-prop title Reporting from the Front, he received international architecture’s most prestigious award, the Pritzker Prize.

Aravena is a proponent, if not always a practitioner of, architecture from below. In appointing him as director, and thereby including many like-minded practitioners in the 2016 Biennale, Baratta pre-empted criticism of the event’s remoteness from real issues. So, again, what next? One Architecture Biennale characteristic that was becoming an issue, especially after the testosterone rush of the 2014 and 2016 Exhibitions, was the predictable gender of the director. Of the 15 Architecture Biennales staged since 1980, only one, that staged in 2010, had a female director (the Japanese architect Kazuyo Sejima). This was becoming embarrassing, and Baratta, in another move that soon seemed prescient, selected as directors of the 2018 Architecture Biennale Yvonne Farrell and Shelly McNamara. As the #MeToo movement gained momentum Baratta had cause to congratulate himself for this decision on many occasions, not least of them during the protest against gender discrimination in architecture staged during the Biennale Vernissage in May 2018 by a ‘flash mob’ including such prominent female architects as Benedetta Tagliabue, Odile Decq, Farshid Moussavi and Jeanne Gang.

The selection of Farrell and McNamara, partners in the Dublin-based practice Grafton Architects, was politic in another sense as well. In selecting a theme for the 2018 Biennale and issuing invitations to contributors to their own curated exhibitions in the Arsenale and the Giardini Central Pavilion, Farrell and McNamara set themselves against the mean-spirited and chauvinistic political tenor of our times, and also, to some extent, against the neo-liberal economic order that has provoked populist discontent in many Western countries.

The selection of Farrell and McNamara, partners in the Dublin-based practice Grafton Architects, was politic in another sense as well. In selecting a theme for the 2018 Biennale and issuing invitations to contributors to their own curated exhibitions in the Arsenale and the Giardini Central Pavilion, Farrell and McNamara set themselves against the mean-spirited and chauvinistic political tenor of our times, and also, to some extent, against the neo-liberal economic order that has provoked populist discontent in many Western countries.

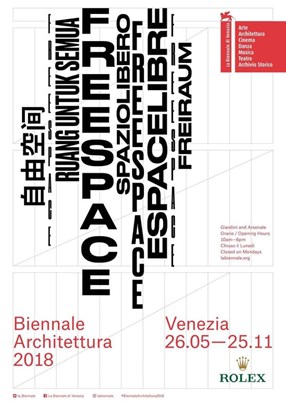

Freespace is the title Farrell and McNamara gave to the 2018 Biennale, a seeming riposte to the regnant belief that everything has a price, and everyone is first and foremost not a citizen but a consumer. So far, so promising, but a title that is convincing enough at first hearing becomes more equivocal under mild interrogation. This is not unprecedented: titular opacity is something of an Architecture Biennale tradition. (The bar for meaninglessness may have been set by Kazuyo Sejima’s People Meet in Architecture.) Partly, this may be explained by the awareness that a Biennale name can only indicate direction, not destination. It’s a rubric that must somehow stretch across the inevitably heterogeneous exhibitions staged in the Biennale’s national pavilions.

That said, there were issues that flowed from concept to content with Freespace. What does the expression mean? Not to be too pedantic about it, but ambiguity is inevitable when one word that can be read as adjective, adverb or verb is elided with another word that is itself inherently elastic and imprecise.

Is ‘freespace’ unowned space or publicly owned space? Unused space or leftover space? Accessible space or unsurveilled space? Or is ‘freespace’ an injunction, a call to liberate space from private possession? The various semantic permutations of ‘free’ and ‘space’ were, of course, intentional and at one with the with the tolerant tone of the 2018 Biennale.

What Farrell and McNamera, who are good people as well as fine architects, were promoting in – and beyond – the 2018 Biennale was architecture that exhibited “a generosity of spirit and a sense of humanity”. What they produced was a rather bloodless Biennale that demonstrated the strength of their humane values, but also the limitations of a liberal critique of the context in which architecture is produced. International architecture’s humanist wing was well represented in Freespace; there were projects by Renzo Piano and Rafael Moneo, Alison Brooks, Niall McLaughlin and Alejandro Arevana, and numerous Irish and Iberian architects. In raising the issues of ‘freespace’, albeit inconclusively, the 2018 Biennale made a case for decency. The question is whether tolerance, reasonableness and generosity are sufficient counters to the bullying, mendacity and wilful disregard for the common weal that, around the world, have been promoted from personal vices to political virtues.

The 2018 Architecture Biennale may have lacked righteous anger or urgency but, as always, there were numerous exhibitions that provoked reflection. Once again, the massive Corderie building in the Arsenale overwhelmed many of the exhibitions staged within it. Tentativeness is ruthlessly exposed in the 300-metre long masonry structure, a 16th century survivor of Venice’s shipbuilding heyday. One of the exhibitions that best stood up to its surrounds was a large-scale fragment of Flores & Prat’s Sala Beckett theatre in Barcelona. Mario Botta’s well-produced entry was a circular cabinet of curiosities featuring images of buildings and their inevitable inhabitants – big bugs. Rafael Moneo’s exhibition focused – and why not? – on his wonderful Murcia Town Hall, accompanied by some text, that in terms of the Venice Architecture Biennale, was positively pellucid: “Free space appears when architecture recedes, in spite of its physical presence. There are moments when we are able to enjoy a sense of pleasure and personal freedom unfettered by architecture.”

In the national pavilion-land of the Giardini, the Russians – always interesting – mounted an exhibition about those defining Russian spaces: train stations, and the vast steppe traversed by the railway tracks.

The Swiss had fun with – and won the Golden Lion for – an exhibition that played around with the scale of domestic interiors, and the Greeks, in the School of Athens, drew upon the formative ‘free space’ of classical antiquity, the public arena for philosophic discourse.

The Israelis examined the fraught subject of shared space – that is, shared, and contested, by different confessional communities – in Jerusalem and the West Bank. (Some nations don’t have to go searching for issues to address). Australia’s exhibition presented an inverted take on indoor-outdoor flow: the interior of the new Denton Corker Marshall pavilion was inhabited by plants while images of houses played on the walls. To achieve this effect 10,000 native seedlings had been transported from Australia to the Ligurian resort town of San Remo, from where, once grown, they were taken to Venice. It was a lot of palaver, and you did wonder, just a bit, whether it was all worth it.

The most equivocal national exhibition was the British pavilion curated by Caruso St John. The exhibition, called Island, was inspired, reportedly, by a passage from The Tempest: “Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises; Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.” Did Islands give delight, or did the exhibition, to cite another of Shakespeare’s works, signify nothing? Caruso St John didn’t install anything in the UK’s permanent Giardini pavilion. Instead, they constructed a temporary viewing platform on top of it. That was it, apart from an urn from which tea was served in the afternoon. Make it of it what you will, it was suggested to visitors; Britain’s Biennale presence could be about “climate change, abandonment, colonialism, Brexit, isolation, reconstruction (or) sanctuary.” It was also literally ‘free space’ (once you’d paid 25 euro to get into the Giardini, that is), and from it you could certainly get good views of the gardens and the lagoon.

But really? You could understand why an exhibition that appealed to some as a droll example of English wit was also viewed with exasperation as a lazily indulgent piece of English smart-arsery.

Visitors from places not in the club of countries with permanent pavilions in Venice’s Giardini could be excused for viewing the UK exhibition as a particularly gratuitous exercise. Perhaps a Brexit reading was the most logical interpretation of the exhibition: Europe – it’s just not worth the effort.

So, it’s farewell to the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale. At the end of the year, Paolo Baratta released the name of the director of the 2020 Biennale. It’s to be Hashim Sarkis, a Lebanese architect who is dean of the School of Architecture and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and principal of his own practice, which has offices in Boston and Beirut. This pivot to academia and to the Arab world was announced with Signor Baratta’s customary emollience: “With Hashim Sarkis, La Biennale has provided itself with a Curator who is particularly aware of the topics and criticalities which the various contrasting realities of today's society pose for our living space”. Hmm, that should about cover everything; the Venice Architecture Biennale 2020 – I’m looking forward to it already.