2017 Gold Medal: Andrew Patterson

Over the course of three decades Andrew Patterson has forged a reputation as a confident designer of striking buildings with great presence. His practice’s portfolio is replete with distinctive projects. Patterson buildings do not just assert their difference against the designs of the architect’s peers; they are also highly differentiated from each other. Consequently, Andrew’s work epitomises bespoke architecture and expresses the paradox of such particularity: he has generated a lineage uncharacterised by familial resemblance. He seems determined not to repeat himself.

That is not to say that Andrew’s work is without defining traits or a common spirit. His architecture is as adventurous as he is aesthetically dextrous. He could surely turn his hand to any style, and like a high-art novelist dipping pseudonymously into genre writing, he has designed lesser-known works in a variety of idioms. But bold form-making is at the heart of Andrew’s practice, along with an appreciation for and masterful deployment of materials. He likes the tough and solid stuff, especially concrete and steel.

This predilection is highly compatible with his declarative impulse. There is nothing tentative about Andrew’s architecture. Not for him, for much of his career, the tread lightly approach. Andrew’s architecture is an architecture of occupation; buildings such as Site 3 (2001), Geyser (2012) and The Lodge at Kinloch Club (2016) take possession of their sites. Often, the buildings burrow in, as is the case with two Queenstown projects, AJ Hackett Bungy (2002) and The Michael Hill Golf Clubhouse (2008). Digging in, as Andrew points out, is not a foreign concept in this country; Māori were sculpting the earth in Aotearoa for centuries before the Europeans turned up.

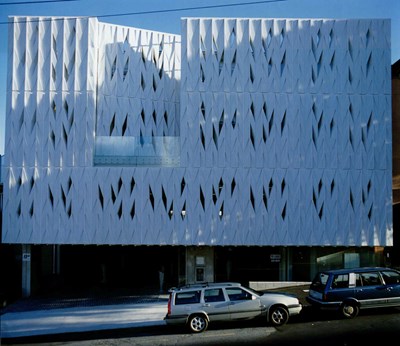

Andrew is at least as comfortable talking about myths as modernism. His attraction to mythologies, and the earth-moving and monument-making civilisations that have produced them, is expressed in strong formal statements such as Anvil and Local Rock House (both 2010) and the Len Lye Centre (2015). It also seems to feed his appetite for pattern-making, a hallmark of his architecture that is there for all to see on buildings as disparate as Cumulus (2003), Stratis (2005) and the Mai Mai House (2007). Pattern is not lightly applied to the façades of these buildings, but seemingly carved out of them. In Andrew’s architecture clarity of concept is never betrayed by timidity of execution.

Unusually for a New Zealand architect, Andrew is not reticent about proclaiming his ambition and ability, or sharing his metaphorical excursions. The evocative nomenclature, an amalgam of Platonic essentialism and capitalist branding, applied to many of his buildings is a promise of excitement.

As David Mitchell puts it: “Only an architect as courageous and skilled as Andrew can get away with fanning our expectations so flagrantly.” He gets away with it because his buildings consistently deliver on the promise of his concepts.

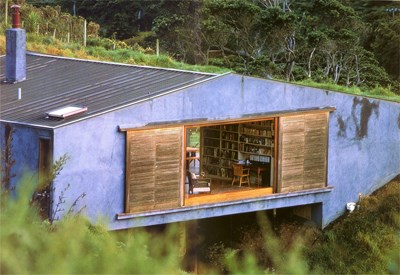

Andrew’s potential was evident as a student – before he graduated he received the commission for his first house (at Karekare, completed in 1986) – and has been realised in a generation’s-worth of assured and often provocative buildings. The Summer Street House (1993), a Ponsonby ‘urban bach’ that substitutes steel wall for picket fence, was an early, and in this case literal, manifestation of his willingness to push the boundaries. Andrew’s professional progress has been paved with architecture awards. All along, he has demonstrated an enviable facility for making the most of a project’s design possibilities, and has long demonstrated a capacity to take a client along with him on an intrepid journey. He has a keen eye for talent, and several of his senior staff have developed into significant practitioners in their own right. He also gone where few New Zealand architects venture, into the big, wide world, designing, for example, the New Zealand Pavilion at the 2012 Frankfurt Book Fair and the New Zealand China Concept Store in Shanghai (2014).

Well into the middle part of his career, Andrew keeps growing, and his buildings keep surprising. Latterly, and significantly in post-earthquake Canterbury, his practice has applied a sensitive touch to the Christchurch Botanic Gardens Visitor Centre (2013) and dwellings (2013-2016) at Annandale on Banks Peninsula. Andrew is a singular figure in this country’s architecture, a star following his own orbit. He is a most worthy winner of the New Zealand Institute of Architects Gold Medal.

– The New Zealand Institute of Architects